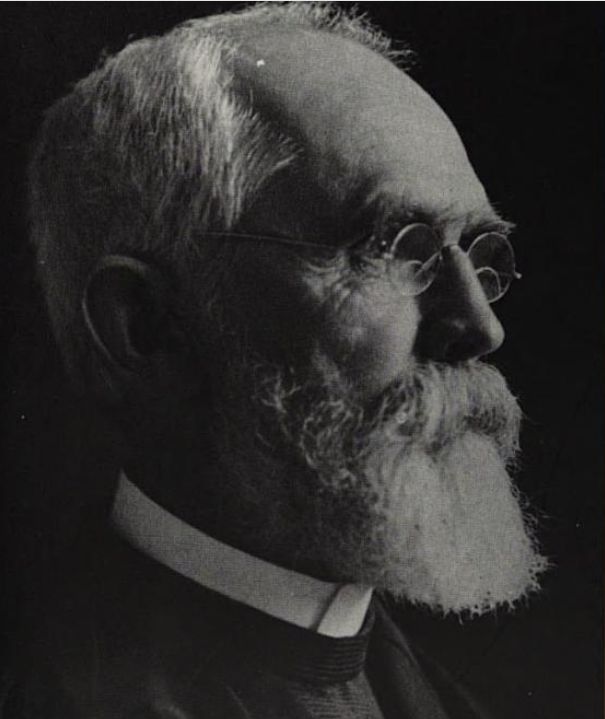

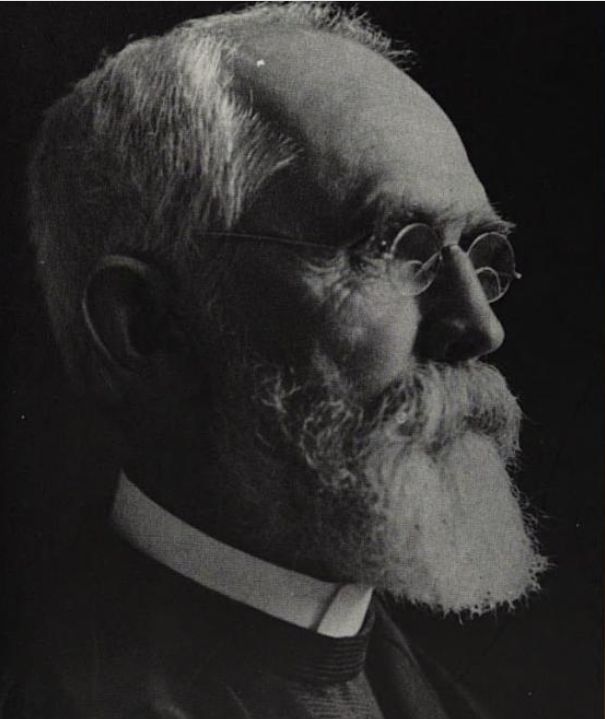

William Porcher DuBose of South Carolina is not well known today, but in the early 20th century, he achieved fame in America and abroad as an Episcopal theologian and author. He was born in Winnsboro, S.C., in 1836, and his father, a wealthy, well-educated planter, saw to it that his intellectually gifted son received a fine education. After attending schools in Winnsboro, DuBose enrolled in the Citadel in Charleston. He had always been a religious young man, but after many months at the military college, he found that his spiritual life was eroding. Then, in 1854, he had a life-changing experience, or as he described it in his memoir Turning Points in My Life, the beginning of his “awakened and actualized spiritual life.”

While returning to school at the end of a break, DuBose and two cousins made an overnight stop in Columbia. After an “uproarious time” at a comedic entertainment, the three young men retired to bed in their hotel room around midnight. While his cousins slept, DuBose knelt down to say his prayers, and in the next few moments, something extraordinary happened. In his memoir, he recalled that suddenly “there swept over me a feeling of the emptiness and unmeaningness of [my prayer] and of my whole life and self. I leapt to my feet trembling, and then that happened which I can only describe by saying that a light shone about me and a Presence filled the room. At the same time an ineffable joy and peace took possession of me which it is impossible either to express or explain. I continued I know not how long, perfectly conscious of, simply but intensely feeling the Presence, and fearful, by any movement, of breaking the spell. I went to sleep at last praying that it was no passing illusion, but I should wake to find it an abiding reality. It proved so.”

On November 19, 1854, DuBose was confirmed at St. Michael’s Church in Charleston. The next phase of his education was at the University of Virginia, and after graduation in 1859, he enrolled in a new Episcopal seminary in Camden, South Carolina, to prepare for the priesthood. Soon afterward he became engaged to a devout and intelligent young lady from Charleston named Nannie Peronneau. After the war began, he entered Confederate service as adjutant to Col. Peter Fayssoux Stevens, the commander of Holcombe Legion. Stevens was an Episcopal priest and would later become noted for his ministry among the slaves and freedmen. Initially state troops serving in the coastal defenses of South Carolina, Holcombe Legion eventually became part of Brig. Gen. Nathan “Shanks” Evans Brigade, a unit also known as the “Tramp Brigade” because it saw service in so many different areas during the war.

DuBose proved himself an able and courageous officer. He was wounded several times, and after being captured by the enemy at South Mountain in Maryland on a nighttime reconnaissance, he was briefly confined as a prisoner of war at Fort Delaware before being exchanged. Because of the unusual circumstances of his capture, DuBose was at first presumed to be dead—killed in action—and after his release from Fort Delaware, he went to Virginia, where he had the very strange experience of reading his own obituary.

DuBose married Nannie Personneau in April 1863, and in the summer of that year, he was in Mississippi during the Siege of Vicksburg and fighting near Jackson. Towards the end of 1863, two influential friends, Thomas F. Davis, the bishop of South Carolina, and General Joseph B. Kershaw, secured DuBose’s appointment as a chaplain in Kershaw’s Brigade. He was ordained as a deacon, and the following year, in February 1864, DuBose traveled to eastern Tennessee to take on the responsibility of the spiritual welfare of hundreds of soldiers and officers. One of his most vivid wartime letters records a winter trek through the gloomy, majestic, snow-covered mountains of North Carolina, while he was on his way to join up with Kershaw’s Brigade. During the journey, only an unlikely, providential encounter with a lone woman in this wilderness saved DuBose and his party from riding directly into a nest of bushwhackers and certain death.

Writing to his fiancée in February 1862, DuBose had speculated on the possibility that the Southern cause of independence might fail, and that if this happened, it might be that it was God’s way of teaching his people a lesson that “here ‘we have no continuing city,’ but that ‘we seek a better, even an heavenly,’” adding, “We ought to remember that we belong to a kingdom that is above the kingdom of this world” and that the Christian life “consists in the gradual withdrawal of our affections from things temporal & fixing them upon the eternal.”

For the young chaplain, the defeat of his earthly cause resulted in exactly such a redirection of life. In his memoir Turning Points, he wrote that on the night when it came over him like a shock of death that the Confederacy was beginning to break, he went out by himself, and there, under the stars, alone upon the planet, without home or country or any earthly interest or object before him, his very world at an end, he re-devoted himself wholly and only to God, and to the work and life of His Kingdom.

After the war DuBose ministered to a congregation in Winnsboro and subsequently served as the rector of Trinity Church in Abbeville, S.C. In 1871, he received an important telegram from Sewanee, Tennessee, informing him that he had been elected Chaplain of the recently established University of the South and also Professor of Moral Science. He accepted this calling, and spent the rest of his life at Sewanee, where he became a powerful intellectual and spiritual force, establishing a School of Theology in 1878 and serving as its dean from 1893 until retirement in 1908. In his last decade, he published a number of books which brought him international recognition as a theologian. Many in the Episcopal Church consider him the greatest theologian that America has ever produced, and all who knew him at Sewanee revered him as a saintly man and the very spirit of the institution.

His theological thought is complex and challenging, but one of his central themes, divine immanence, is traceable to his supernatural experience of God’s presence as a young cadet. In An Apostle of Reality, his nephew Theodore DuBose Bratton wrote: “Dr. DuBose’s contention is that God Transcendent is unknowable to us; that God Immanent in the Son is beautifully known to us; that God is infinitely knowable to us through the Holy Spirit.”

He likened his supernatural encounter to the human experience of falling in love, which “comes simply because of the fact that the man is made for the woman and the woman for the man, and neither is complete or satisfied without the other. The divine love in which God makes Himself one with us comes simply for the same reason, and because of the fact, so perfectly expressed in the ever new old words: ‘My God Thou hast made me for Thyself, and my soul will find no rest, until it rest in Thee.’”

For DuBose, his wife’s love was “next to God’s love, the highest & most precious reality.” In his book The Reason of Life, he emphasized the sacred nature and importance of marriage:

The impulse to discredit or destroy institutions that go back beyond all memory or knowledge of man—such, for example, as that of marriage—because of imperfections or failures or abuses, instead of reading their slowly unfolding meaning, and looking forward and patiently working up to their future ideal perfection, however far off, is an impatience incapable of cooperation with Him to whom a thousand years are as one day. The divine intent of marriage…is the highest ideal of human relation and association, of social purity and perfection. Discredit of it, leading inevitably to corruption in it, is poison to the root of human life.

In 1898, writing to a friend who had sought his opinions about the war of 1861-1865, DuBose defended the South’s withdrawal from the union and its cause of independence. He contended that when it became apparent to the South that the government which had been established by the two sections of the country was not going to abide by its own compact (the Constitution), and was “going to subordinate the law to which they had agreed to another “higher” law to which they had not agreed,” then the Southern States acted on their right to secede. He added, “No one questions now that slavery had to be abolished, but in the immediate quarrel the South was legally and constitutionally right, and the method and spirit of the North forced the manhood of the South into the cause it pursued, and rendered any other impossible for it with self-respect.”

DuBose died in 1918 and is buried in the University cemetery. The date of his death, August 18, is commemorated as a “lesser feast” day of the Episcopal Calendar of the Church Year. There are numerous books by and about William Porcher DuBose, and his wartime correspondence (unknown and unpublished for nearly 150 years), was published in 2010 as Faith, Valor and Devotion: The Civil War Letters of William Porcher DuBose.