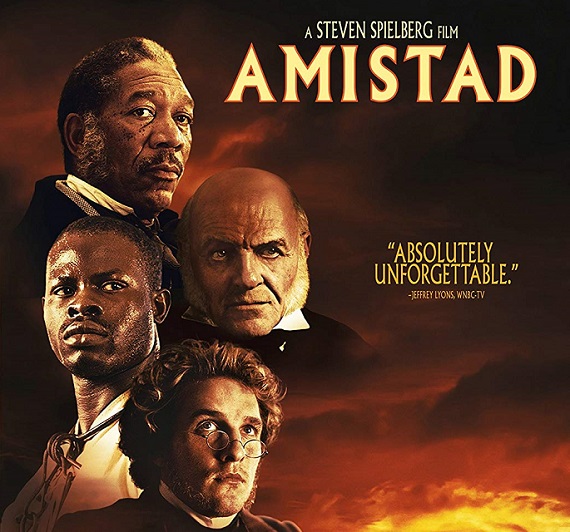

5. Spielberg’s Amistad (1997)

If Amistad is not yet a household word like ET or Jurassic Park, it soon will be with the power of Steven Spielberg behind it. (When I started this review awhile back, that was my first sentence, but I may have been wrong. Late reports indicate the box office is lagging.)

Amistad is really two movies. One, about the 19th century slave commerce between West Africa and Latin America, is a good piece of film-making. The other, about American politics and law, is completely hokey and misleading.

Nobody knows for sure, but from the mid-1500s to the mid-1800s between11 and 15 million black Africans were transported to the New World, a vast undeveloped region with a voracious appetite for unskilled labour. Every maritime nation in Europe participated in this trade. Only about five to six percent of the Africans ended up in North America, the vast majority going to South America and the Caribbean. By the time of the Amistad incident, 1839, the market was largely limited to Cuba, a Spanish colony, and Portuguese Brazil. And the shippers involved were limited to Spanish, Portuguese, and American New Englanders.

In case you haven’t heard, the Amistad was a Spanish ship bound from West Africa with captured slaves to be sold in Cuba. The captives revolted and killed most of the crew. After drifting for a long time, the ship was intercepted by a U.S. coast guard vessel and taken into a Connecticut port. (How it got that far north is not made clear in the movie.)

Thus the Amistad case relates largely to the history of West Africa and Latin America. Only by an accident of navigation did it become an American issue, and then only as a case in admiralty and diplomacy. In the long run it was a minor case that set no precedents. Spielberg wants to make this incident bear the whole weight of the American slavery that lasted two and a half centuries and the Great Unpleasantness that ended it. Thousands of Amistad study kits were sent out to schools with this goal. The trouble is, as an account of American history, the thing will not bear the weight. The Amistad had exactly nil influence on (eve of Civil War figures) the nearly four million American slaves (most of whom had been here for some generations); on the 395,000 slaveholding families; on the 488,000 free blacks (most of whom, contrary to the usual assumption, were in the South); nor on the issues and events which led to the bloodiest war in American history. Of course, if there had been no slavery and no slave trade, there would today be no such thing as an African-American. The people would not exist.

One of Spielberg’s assistants called me early on, wanting advice on the characterisation of John C. Calhoun, who I am supposed to know something about. For a moment visions of fat Hollywood fees danced before my eyes. Then, I remembered what Grandmother said: Stand up straight, look ‘em in the eye, and always tell the truth. I had to say, well Calhoun had nothing to do with the Amistad case and nothing to say about it. (The assistant, by the way, identified himself as a South Carolinian. By his speech and the fact that he had had a scholarship to Harvard, I assume he is an African-American. He was very good, almost as slick as a young Strom Thurmond. I would advise him to come home and go into politics.)

Calhoun is shown in the movie (and the actor who plays him is good, by the way) as declaiming about slavery and impending civil war in relation to the case. This did not happen and could not have. I have since learned where they got it. Like Ken Burns, Spielberg’s people have been taken in by the great Boston-o-centric stream of American myth and “history.” They got the idea of using Calhoun from Samuel F. Bemis’s romanticised biography, John Quincy Adams and the Union, as well as the idea that the case was some kind of major event and triumph for Adams. The idea of having Adams, one of the nastiest major figures in American history, portrayed by Anthony Hopkins as a shrewd, cuddly old teddy bear, I assume they thought up in Hollywood itself. Get his picture and look at that cold hateful face some time. I guarantee the next time you have indigestion you will see it in your nightmare as one of the devils tormenting you in Hell. Randolph of Roanoke called him Blifel after the Puritan hypocrite in Tom Jones.

Bemis claimed that Calhoun introduced resolutions in the Senate on the Amistad case to “thwart” Adams. (The statesman Calhoun never acted from such petty motives.) Bemis even quoted two of the resolutions, conveniently leaving out the third which was specific. In fact, Calhoun’s concern at this time was a different question. British officials in Bermuda and the Bahamas were undertaking to free the slaves on American coastal vessels that came by stress of weather into their waters (It was common for plantation families to move with their slaves from the South Atlantic to the Gulf coast states by ship.) The British freed any who came into their hands, as a matter of policy. They also executed those guilty of killing, like the Amistad Africans, and later paid indemnity to the U.S., an admission of illegality.

Adams was at this time a marginailsed figure, a failed President who could not even get elected Governor of Massachusetts. Calhoun was much more influential at this point. By falsely setting up Adams as an antagonist to Calhoun, Bemis and the movie lend more importance to Adams than is deserved. There is also the question of motivation. It is all a love of liberty on Adams’s part, according to this rendering. (Part of the larger myth that the later brutal conquest of the Southern people by the government to establish a political and economic empire, something Adams longed for but did not live to see, was to be entirely explained as a righteous crusade to free the suffering black man.)

Adams had become President in an election that was brokered in the House of Representatives under cries of a “corrupt bargain.” He had proceeded to propose grandiose plans of centralisation and mercantilism, repudiating everything that had been taught by Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe. He was immediately shot down and destroyed by Southern strict constructionists. He hated what one of his descendants called “the sable genius of the South” and devoted his last years to attacking it. It had nothing to do with freedom or with the welfare of people of African origin.

Foreign importation of slaves to the U.S. was illegal and negligible after 1808. Participation in the slave trade to other countries was also illegal for Americans. But in fact, New Englanders, who had plenty of shipping, continued to invest and participate in the traffic from Africa to Latin America on a considerable scale, including the Brown family who endowed Brown University, and Thomas H. Perkins, the Boston merchant prince who bankrolled Daniel Webster’s career, as well as many lesser fry. The last known New England slave ship, sailing out of Maine, was captured in1862, a year in which oceans of blood were being shed for the alleged purpose of freeing the slaves.

By the 1830s the British, who had not long before been the largest slave traffickers in the world, had declared emancipation (of a sort) in their colonies and undertaken to suppress the transatlantic trade by naval power. Many governments, including the U.S., approved the object, but they were not too happy about the Brits claiming rights of search and seizure of other countries’ ships on the high seas, something which indeed Americans had declared war against in 1812. In 1842, Americans agreed to participate in the suppression of the trade as long as the Brits followed strictly laid out rules. Southern naval officers, diplomats, and other officeholders carried out their duties in this regard conscientiously and generally favored the policy. For instance, Henry A. Wise, later governor of Virginia and a Confederate general, while he was U.S. Minister to Brazil in the 1840s made serious efforts to intercept the New Englanders trading Africans to that country.

The fact was, except for a few hotheads seeking to provoke the Yankees, there was no interest in the South in slave importations after the early 19th century, even though the demand was high. The natural increase was abundant, fertility and longevity being almost equal to the white. (There is still a difference today.) No one wanted to disrupt the settled and peaceful system that existed. The Confederate States Constitution, unlike that of the U.S., absolutely forbade foreign slave importations. The determination of Southerners to prevent malicious outsiders from interfering in their society is, of course, an entirely different question. Amistad diverts attention away from the real issues of American history.

Some other things about this movie that I find distorted. Adams makes a pretty speech about liberty to the Supreme Court. I do not find evidence that this speech was actually delivered. What appears in the printed court record is legalistic, though it is possible the speech could have been made in unrecorded oral argument. In the film, Cinque, the leader of the Amistad captives, is present in the Supreme Court, which did not happen. And there is a totally fictional character, played by Morgan Freeman, an affluent free black man. Contra the film, no black man, no matter how affluent, would have been permitted to sit in a courtroom or ride in a carriage with white people in the North in 1839, especially in Connecticut.

This is mentioned in the film bur not dwelt on: The Northern judges who first dealt with the case ruled against the freedom of the Amistad captives. The Supreme Court, with a majority of slaveholding Southerners, rendered the proper decision. The Africans had been illegally seized and were freed. Then, according to American law, they had to be sent back to Africa. In addition, a law professor friend tells me the movie badly distorts the legal issues and proceedings of the case, though these take up most of the film.

Here is the real clincher, which you can bet is not in the movie. Samuel Eliot Morison, one of the leading American historians of all time, wrote in his Oxford History of the American People that Cinque, the leader of the Amistad blacks, went back to West Africa and became a slave trader himself (1965 edition, p. 520). Being from Boston, Morison did not have to give any source for this statement and does not. Some writers have affirmed, others have denied this story, none of them having cited any source. In fact, except for the court record, everything that has been portrayed about the Amistad case is in the realm of romance rather than historical scholarship. The court record is full of lawyers’ and diplomats’ lies, but at least it’s a document.

Morison’s story is inherently likely. He was well connected in New England maritime circles. New England ships frequently went to the coast of West Africa to sell rum and buy slaves and could have easily heard news of Cinque. Morison could have had the story word of mouth from an old man who had been there, or his descendants. Also, that Cinque became a slave trader is highly plausible. What else could the man do? His native village had been dispersed. West Africa had little else to trade for European goods except its people. It would have been the best entrepreneurial opportunity open to him. The region’s economy and politics consisted largely of competition between chiefs for market share of captives to be sold.

To further develop the hokeyness of Amistad’s portrayal of American life and politics, let me review the unknown history of another slave ship case. In 1858, a U.S. navy vessel intercepted a suspicious looking ship near the Cuban coast. It turned out to be the Echo out of Providence, Rhode Island, with over 400 Africans on board, many of them in very miserable condition. The officer who captured the slaver was John N. Maffitt, who a few years later would be famous as commander of the Confederate raider Florida. The captain and owner of the slaver was Edward Townsend, a well-educated man from what passed for a good family in Rhode Island. He alleged that the Africans were all war captives or families of executed criminals and he had saved them from certain death. He also said that had he completed his voyage, he and his silent investors could have cleared $130,000, a staggering sum in those days.

Maffitt took Townsend to Key West to be prosecuted. The Northern-born federal judge, later a Unionist, refused to take jurisdiction. Maffitt then had him sent to Boston, where the court had jurisdiction on the presumed point of origin of the Echo. There the federal judge also refused to proceed and Townsend walked free, though guilty of a crime equivalent to piracy in U.S. and international law.

The Echo, its crew and captives were taken to Charleston. The people of Charleston provided them with food, clothing, and other necessities and treated them with sympathy. The U.S, District Attorney in Charleston was James Conner, who a few years later would lose a leg fighting in the Confederate army. Unable to get hold of Townsend, he vigorously prosecuted the crew. The juries felt, however, probably correctly, that the miserable polyglot lot were as much victims as criminals, having been shanghaied or tricked into the voyage. The mortality rate of the captives in the Yankee slave ship Echo was over 30 percent. The survivors were returned to Africa, though it was reported that many of them did not want to go.

I recount this case to provide some contrast to the cartoon version of the history of American slavery given in the movie. The movie gives a distorted picture and very possibly will arouse hatred at a time when it is the last thing needed. The rehearsal of ancient guilt and outrage is not a healthy activity for Americans, African or otherwise. It requires selecting out a few scapegoats to blame for all the long record of the crimes, misfortunes, and follies of mankind. The psychologists call this projection. Its purpose is to save us the trouble of examining our own problems and sins.