In yet another attack on American history and heritage, the George Washington University in Washington, D.C. is changing the name of their sports team, which is known as the Colonials. GW Today, the University’s official online news source, reported, “The George Washington University Board of Trustees has decided to discontinue the use of the Colonials moniker based on the recommendation of the Special Committee on the Colonials Moniker. Both the board and the special committee ultimately determined that given the division among the community about the moniker, it can no longer serve its purpose as a name that unifies.” The article further stated, “For opponents, Colonials means colonizers who stole land and resources from indigenous groups, killed or exiled Native peoples and introduced slavery into the colonies.”

The latter statement does not square with history. While there were cases of colonists seizing land from Native Americans against their will, there were also cases where they legitimately purchased it from them. In some of the latter cases, Native American tribes later tried to seize back the lands which they had legitimately sold. There was fault on both sides. The statement that the colonists “introduced slavery into the colonies” is completely false. Native American tribes were enslaving each other at the time Christopher Columbus first landed in the New World in 1492. The first slaves which the colonists took were Native American slaves and they did so in imitation of the practices of the Native Americans themselves. In fact, it was among the colonists in the Eighteenth Century that sentiment for abolishing slavery began. Writing of this, Dr. Michael J. Crawford begins his discussion with a reference to George Walton, a Quaker in North Carolina:

“When George Walton joined the Quakers and committed himself to the manumission of their slaves, he became a first-generation participant in one of the most remarkable revolutionary freedom movements in the history of mankind, the movement to abolish slavery. By the time of the invention of writing, slavery already existed. While the annals of history include accounts of numerous slave revolts, few of those revolts had as their object the destruction of slavery as a system before the eighteenth century. Several individuals questioned the right of any person to own another before the eighteenth century, but theirs were solo voices, not those of a chorus. From Plato to Locke, political philosophers accepted slavery as a given, an inevitable condition for a substantial portion of the human population.

“In 1772, when Walton began his manumission crusade, more than three-quarters of people on earth were not free, according to one reckoning. These included slaves bound to work for their masters, serfs bound to the land, and peasants bound by debt to work for their landlords. Some form of bondage was the condition of much of the population of Russia, India, China, Africa, and the Americas. When Walton dreamed of Christ as a small black child, legal systems from Patagonia to Labrador promoted the enslavement of black Africans and their descendants and no law restricted the transportation of slaves from Africa to the Americas. In the period from 1520 to 1820, when some 2.6 million white Europeans made the transatlantic voyage to the Americas, slave traders carried some 8.7 million black Africans to the New World. Each year from 1791 to 1800, nearly 80,00 blacks from Africa arrived in shackles on American shores.

“Beginning in the mid-eighteenth century, the most remarkable revolution in the story of human freedom took place with astonishing rapidity. By the end of the next century, serfdom and slavery had been ended by law almost everywhere and few could be found to defend their legitimacy. In 1808, both the U.S. Congress and the British Parliament outlawed the international slave trade. The United Kingdom subsequently negotiated treaties with several European nations to end the international slave trade, and in 1819 the United States made it a crime of piracy for its citizens to engage in that trade, a crime which was punishable by death. The Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron diligently patrolled West Africa’s ‘Slave Coast’ to enforce the prohibition, as did a smaller U.S. Navy force. By 1830, Haiti, Mexico, Central American countries, and several Northern states of the United States had abolished slavery and gradual emancipation laws were bringing an end to slavery in Rhode Island, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and most of South America (with the notable exception of Brazil). The British abolished slavery in their colonies in 1833. An act of 1843 made slavery illegal in India, although the ban had to be reenacted in 1861. Tsar Alexander II signed the Emancipation Manifesto ending Russian serfdom in 1861. The Dutch enacted gradual emancipation for their colonies in 1863. The Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution ended slavery in in the United States in 1865. Spain adopted gradual emancipation for Cuba’s slaves in 1870 and ended slavery in all its colonies in 1886. Brazil finally ended slavery in 1888.”

The 1619 Project claims that the American Revolution was fought to sustain slavery. Dr. Crawford shows that the opposite is true. It began the process for freedom of the slaves in both the North and the Upper South. The process in the latter was eventually aborted in the Nineteenth Century by New England abolitionism.

And it is not only the name of the university’s sports team which is under fire. Caleb Francois, a GWU student, wrote in an opinion piece in the Washington Post that the name of the university itself is a problem. He stated, “Even the university’s name, mascot, and motto – ‘Hail Thee George Washington’ – must be replaced.” He further stated, “But it’s not just the university’s name that’s a problem. Just blocks from the main campus is the Mount Vernon Campus, named for George Washington’s former slave plantation. Every day, hundreds of Black students walk on a campus named after an enslaver of men and study at a site named after dark parts of history.” John Nolte noted of this in Breitbart, “What is notable is the Washington Post running an op-ed that trashes something named after the Father of our Country – you know, like the Washington Post.”

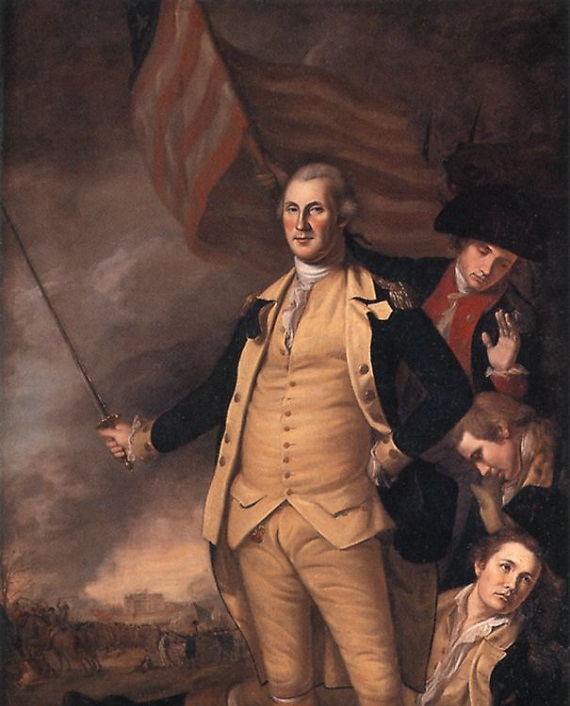

This, once again, does not square with history. Dr. Jerry T. Newcombe, who coauthored a book about George Washington, stated “that Washington was a fourth-generation Virginia gentleman farmer. Slavery was built into that system. Washington inherited slaves first by birth and later by marriage.” Edward G. Lengel, who is the former editor of the George Washington Papers at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, stated, “The problem of slavery increasingly bedeviled Washington in both its economic and moral dimensions. Slave labor was integral to production on his primary properties [which he also inherited] just as it was to other large plantations in the South. He had long taken this for granted, relying on ostensibly free labor a one of many cost-cutting devices. By the early years of the Revolution, however, Washington started speaking of is hope to ‘get clear’ of slaveholding.” In a letter to John Francis Mercer on September 9, 1786, Washington stated that it was “among my first wishes to see some plan adopted, by the legislature by which slavery in this Country may be abolished by slow, sure & imperceptible degrees.” In 1796, he began laying plans in hope of selling off his western lands and renting his outlying Mount Vernon farms to use the proceeds to free his slaves. He died three years later, before this could be achieved in his own lifetime, but he provided for the freedom of all of his slaves in his will, making him the only Founding Father to fee all of his slaves. Lengel stated, “Time had taught him to view their continued bondage as a grave moral injustice.” He also stated that, in Washington’s opinion, “by undermining the basic principles of industry, such moral labor degraded not just the slaves themselves, but those who owned them.”

Nor were Washington’s sentiments rare in Virginia at the time. During the Revolutionary War, Northern states began enacting the gradual abolition of slavery. Such sentiment was also strong in Virginia, which had been agitating for abolition of the slave trade starting in 1770. Virginia also became the first civil jurisdiction in the world to abolish the slave trade upon its achievement of independence in 1776.

Francois also decried, “No African languages are taught at the university.” Nolte said in response to this, “Why would a university teach African languages? College is about preparing you for the future. I cannot think of a single African language that is a common language.” Nolte is correct. In Africa, native languages are strictly tribal and it is the European languages from Africa’s colonial period which are the unifying languages in African countries, like it or not.

Dr. Crawford pointed out how slavery was abolished in the Western world and some other parts of the world as well, but this has not been the case in much of the Third World. There, slavery still flourishes to this day. In 1860, there were three and a half million black slaves in the United States. Today, in 2022, there are still six million black slaves in Sub-Saharan Africa. And of the African slaves who came to the New World, 307,000 came to what is now the United States, 241,000 came to Mexico and Central America, 3,763,000 came to South America, and 4,021,000 came to the Caribbean Islands. It would seem that the legacy of slavery in the Caribbean and South America should garner more attention than that of the United States, not only because there were far greater numbers of them there, but also because it lasted longer there. But instead, the American South is treated as though slavery was exclusive to it by the radical left. The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, founded in England in 1839, still exists there today as Anti-Slavery International, and continues to bring attention to slavery in different parts of the world today. So do other organizations, such as Arise. Human trafficking is one form which still exists, even in this country.

These facts demonstrate that what is wrong with the university and its sports team is not who or what they are named after, but what is being taught there that such decisions are being made about naming and that its students there have views which are so divorced from historical reality. Dr. Newcombe stated it correctly, “The Marxist iconoclasts of today, such as the triggered student at George Washington University, or the editors at the Washington Post, who promulgated such ideas to a wider audience, have no appreciation for the sacrificial contributions of those who went before us, that we might be free.”

Sources:

“GW to Discontinue Use of Colonials Moniker,” GW Today. https://gwtoday.gwu.edu/gw-discontinue-use-of-colonials-moniker

Caleb Francois, Opinion: “George Washington University Needs a New Name,” Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/05/09/george-washington-university-needs-new-name

John Nolte, “Washington Post Op-Ed Demands Name Change at George Washington University,” Breitbart. https://www.breitbart.com/the-media/2022/05/11/nolte-washington-post-op-ed-demands-name-change-at-george-washington-university/

Jerry T. Newcombe, “Plans to Further Defrock Washington,” D. James Kennedy Ministries. https://www.djameskennedy.org/article-detail/plans-to-further-defrock-washington

Michael J. Crawford, The Having of Negroes Is Become a Burden: The Quaker Struggle to Free Slaves in Revolutionary North Carolina. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2010.

Edward G. Lengel, First Entrepreneur: How George Washington Built His – and the Nation’s – Prosperity. Boston: Da Capo Press, 2016.

Beverly B. Munford, Virginia’s Attitude Toward Slavery and Secession. New York: Negro Universities Press, 1969 (1909).

Patricia S. Daniels, Atlas of American History: From Ancient Cultures to the Digital Age. Washington: National Geographic, 2021.

Anti-Slavery International. https://www.freetheslaves.net

Arise. https://www.arisefdn.org

The Louisiana state government in its recent legislative session literally canceled George Washington’s Birthday state holiday, which is still an official national holiday, and replaced it with the so-called “President’s Day,” state holiday. In my opinion, that is just another way in the ongoing campaign by radical leftists to erase the Founding Fathers and the founding principles upon which our nation was founded and replace them with their poisonous radical agenda.

The first casualty of war is truth.