On the morning of July 5, 1880, Colonel E.B.C. Cash and Colonel William M. Shannon faced each other with pistols near Du Bose’s bridge in Darlington County, S,C. At a word of command, Shannon fired quickly, splashing the muddy ground at the feet of his adversary. Colonel Cash, an experienced duelist with a sinister reputation, coolly took aim and fired. Seconds later, Colonel Shannon, believed to be the last man shot in a “high-toned” pistol duel anywhere in the United States, lay dead.

The killing of Colonel Shannon sent shock waves across the state and spurred the South Carolina legislature to enact strict new laws prohibiting dueling and disqualifying from public office anyone who had taken part in one. The incident also had a profound effect on one of the men in attendance that fateful morning. Dr. Simon Baruch, a close friend of Shannon, had reluctantly agreed to witness the affair. Hoping to avert bloodshed, Dr. Baruch had secretly alerted the local sheriff. But the intervention of the law came too late. Haunted by what he believed was a needless and tragic death, Simon Baruch decided to move his family and his very successful medical practice to New York City.

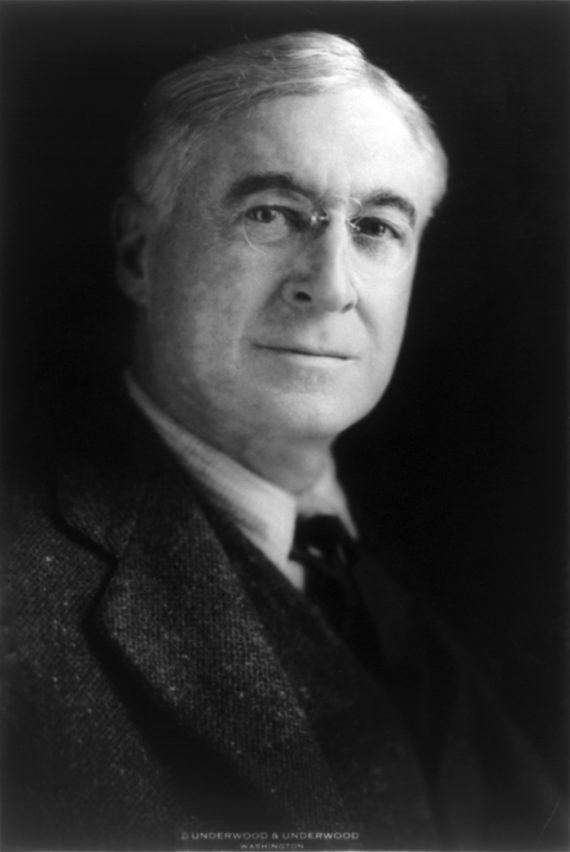

Had the Darlington County sheriff ridden a little faster that July morning, the world might never have heard of Wall street financier, Presidential cabinet member and consummate Washington insider Bernard Mannes Baruch. He was born August 9, 1870 in Camden, S.C. The second of four sons born to Simon and Isabelle Baruch, Bernard later recalled the family’s move north of the Mason/Dixon line with nostalgia and regret. “There was a Huckleberry Finn or Tom Sawyer quality in how we lived,” wrote Baruch. His was a world familiar to generations of Southerners—a world of shotguns and fishing poles; of classic books and religious devotions; of easy familiarity and high courtesy. The courtly manners and high ideals he learned as a barefoot boy in the impoverished, agrarian South never left him, even at the pinnacle of wealth and power. The man later denounced by Henry Ford as the archetypal “international Jew;” adviser to presidents, kings and captains of industry; Bernard Baruch remained, throughout his life, a gentleman of the Old South.

Baruch’s Southern roots ran deep. His mother’s family were Sephardic Jews descended from Isaac Rodriguez Marques. Marques, believed to have immigrated from Denmark, established a booming shipping business in New York in the 1690s. A grandson of the patriarch changed the family name to Marks and served with distinction in the Continental Army during the America’s War for Independence. By this time the Marks family had been transplanted to Charleston, S.C. Baruch’s grandmother, Sarah Cohen, daughter of Deborah Marks and Rabbi Hartwig Cohen, became the bride of a gallant young “upcountry” merchant and planter named Saling Wolfe in 1845. From their union came 13 children, including Baruch’s mother Isabelle.

The Wolfe family mansion in Winnsboro, S.C. was among the first put to the torch when Sherman’s army came to call in the spring of 1865. One of Baruch’s favorite family stories from that terrible time concerned a portrait that his mother had painted of her fiance, Bernard’s father, Simon. “When Sherman’s raiders were setting fire to Saling Wolfe’s house,” Baruch wrote, “Mother, who was about fifteen, rescued this portrait. She was carrying the picture across the yard when a Yankee soldier wrenched it from her hand and ripped it with his bayonet. When she protested, he slapped her.”

The assault brought immediate retribution from a certain Captain Cantine, the Union officer commanding the detachment. Wielding the flat of his sword, the outraged Union officer treated the cowardly recruit to a merciless beating. From this chivalrous act a romance began to bud. This was too much for Belle’s father. Marriage to a Gentile was one thing. But marriage to a Yankee was out of the question! His daughter continued to exchange letters with the dashing young captain until her fiance returned from Confederate service and, in 1867, brought her under the chupa, the traditional Jewish wedding canopy.

An interesting footnote to this story appears in Bernard Baruch’s memoirs. He recalled that during World War I, while he was chairing the War Industries Board, a young man besought his assistance in getting overseas to the fighting front. He carried a letter of introduction written by Baruch’s own mother. “The bearer of this,” wrote Mrs. Baruch, “is a son of Captain Cantine.” I know you will do what you can for him.” And, of course, Baruch did.

In contrast to the Wolfes, Marks and Cohens, Bernard’s father was a recent immigrant. Born in Schwersenz, Prussia in 1840, Simon Baruch left the Royal Gymnasium in Posen at the age of 15 for the strange new world of Camden, S.C. With the aid of Mannes Baum, a local merchant, Simon put himself through medical school and soon established himself as a successful country doctor. It was Mannes Baum who presented Baruch with a handsome uniform and sword when the young surgeon joined the Third Battalion, South Carolina Infantry, on April 4, 1862.

In the course of his three years of military service, Baruch was often under direct enemy fire—and not always as a non-combatant. During the Confederate retreat from Cedar Creek, he tried desperately to help General Jubal Early rally the beleaguered rebels for just one more stand. At the battle of South Mountain, Baruch performed major surgery outdoors on a makeshift table made from a churchhouse door and two large barrels. As bullets whizzed overhead, Baruch and his orderlies continued their grim work until a Union army surgeon rode up and offered assistance. It was only then that Baruch realized that he had become a prisoner of war.

Exchanged a few days after the battle of Sharpsburg (Antietam), Baruch was captured again at Gettysburg. At the field hospital in Black Horse Tavern, Baruch worked for two days and nights to save the lives of the wounded Confederate and Union alike. As Lee’s army began the long retreat South, Baruch was ordered directly by the commanding general to stay behind with the sick and wounded. Again a prisoner of war, Baruch was overwhelmed by the kindness and cooperation he received from Union officers and civilians. Abundant medical supplies and even such undreamed-of luxuries as fresh butter, eggs, wine and coffee were provided for the Confederates. After six weeks of relatively pleasant captivity, Baruch was shipped to Baltimore for confinement in the prison of Fort McHenry. Two months later, Baruch was exchanged a second time.

In March 1865, surgeon Baruch was captured for the third and last time—without even knowing it. Stricken with typhoid fever while treating Confederates wounded at Averyboro, N.C., Baruch was unconscious when General Sherman’s troops passed through the area. He awoke to learn that he had been “paroled” and that the war, for him, was over at last.

Like so many Southerners, Dr. Baruch returned home on crutches to find his house burned and his country under military rule. “Through much of my childhood no white man who had served in the Confederate Army was allowed to vote,” wrote Bernard Baruch. Fed up with pandemic corruption, skyrocketing taxes and the complete suppression of their most deeply cherished rights, Southerners responded predictably. “So oppressive was this state of affairs that even a man like my father could write a fellow veteran of the Confederate Army that death was preferable to living under such conditions.”

Simon Baruch would say little of how he and other members of the Ku Klux Klan persuaded Camden’s “carpetbag” officials and their “scalawag” allies to ply their trade elsewhere. But Bernard’s earliest memories were of his mother sitting up late, behind a barricaded door and with a loaded shotgun, while his father was away on “political business.” Despite the violence and hatred of the times, Bernard recalled that Dr. Baruch once went to the deathbed of a noted scalawag. “Nor did Father have any prejudice against the Negro or any grudge against the North,” wrote the younger Baruch. “Reconstruction rule,” he said, “was oppression to Father and he fought to free the South of it. It is tragic that the Negro got trapped in this struggle, which embittered race relations to this day.”

Bernard Baruch had only fond memories of the blacks he knew as a boy. Foremost among them was his nurse, Minerva, who brightened many an evening with stories of Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, Brer Terrapin and a doleful lion named “Bolem.” Like so many of her generation, Minerva was generous and loving but not overindulgent. “Minerva would not have favored progressive education,” wrote Baruch. “When she was an old woman, she would visit me at my South Carolina plantation and delight in telling my Northern guests how she used to paddle me for my bad behavior.” As a grown man—one of the wealthiest and most powerful in America—Bernard Baruch was still addressed by the venerable nurse as “chile.” Minerva’s children, especially her son Frank, were the Baruch children’s first playmates. Frank, as Bernard later recalled, “could beat us all at fishing and hunting and could snare birds, an achievement I admired.”

Bernard Baruch’s boyhood was not only a world of black and white—there was Jew and Gentile also. Camden’s Jewish community consisted of just six families, but as Baruch noted, “they were all respected citizens.” The most distinguished of these were the De Leons, which furnished the Confederacy with a Surgeon-General and a diplomatic agent to France. Since the community was too small for a synagogue, Camden’s Jews worshiped at home. “On Saturdays,” Baruch wrote, “we wore our best clothes and shoes and were not permitted outside the yard of our own home.” Out of respect for the Christian Sabbath, Baruch recalls that “Mother made us dress up and ‘behave ourselves’ on Sundays as well.”

Baruch’s mother had been raised in a strictly observant home. His father was more lax regarding dress and diet, but he took his responsibilities to the Jewish community seriously. As head of the region’s Hebrew Benevolent Association, Dr. Baruch urged his co-religionists to build their lives on “high morality” of the Bible—a sentiment shared by his Christian neighbors.

“In South Carolina,” Bernard recalled, “we never suffered discrimination because we were Jews.” Such was not the case in New York, where Baruch’s daughters, despite the fact that they were raised in the Episcopalian faith of their mother, were denied admission to several private schools and even barred from the dancing school their mother had attended.

Publically attacked by such notorious anti-Semites as Gerald L. K. Smith, Dudley Pelley and German dictator Adolph Hitler, Baruch clung, throughout his life, to the tolerance, goodwill and mutual respect he had experienced as a boy in the South. “I have told my children not to be blinded to the greatness of America by the pettiness of some of the people in it,” wrote Baruch.

“The priceless heritage which America has given us,” Baruch noted, “…the heritage which is America—is the opportunity of being able to better oneself through one’s own striving. No form of government can give a person more than that. And as long as that heritage remains ours, we will continue our progress toward better religious and racial understanding as more and more of each of us comes to be recognized for his or her own worth.”

This article was originally printed in Southern Partisan magazine, 3rd Quarter 1994.