21. Faulkner in Film

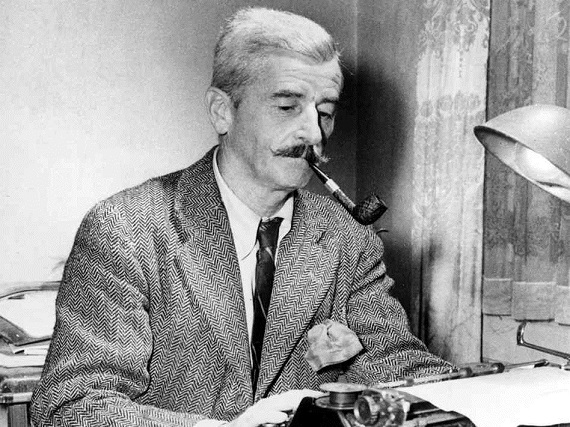

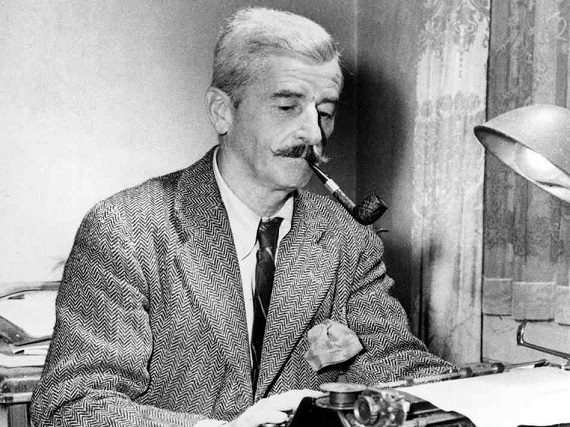

Southern viewers must naturally be interested in what Hollywood has done with America’s greatest 20th century writer, William Faulkner of Mississippi.

**Intruder in the Dust (1949). Perhaps the most faithful of all Faulkner’s work on film, and a realistic portrayal of Southern life in the early 20th century. An old lady (Elizabeth Patterson) and two boys, one white and one black, go to great lengths to save a cantankerous black man from a murder charge and lynching.

**The Reivers (1969). A pretty good rendering of the disobedient Memphis escapades of a boy and his two feckless adult companions. Realistic and a lesson in what happens when you disobey Grandfather’s instructions about the conduct of a gentleman.

**Tomorrow (1971). In this bleak dramatisation of a Faulkner story, Robert Duvall makes one of his earliest and best performances. He is a poor farmer who takes in a dying woman and her baby and later faces the loss of the boy he has raised as his own son.

**William Faulkner’s “The Old Man” (1988). A story from Faulkner’s book The Wild Palms. “The Old Man” is the Mississippi River. A convict is temporarily released to fight the raging floods in the 1920s. In the process he finds love and redemption.

**Two Soldiers (2003). A poor Mississippi farm boy goes to Memphis to enlist the day after Pearl Harbor. His little brother follows with the intention of joining the war. Based on a story about the little brother’s experiences and a testimony to Southern wartime patriotism.

(T) Today We Live (1933) is a big- star (Gary Cooper, Joan Crawford, Robert Young) film based on Faulkner’s story “Turnabout,” about England in World War I, but it rather misses the point–too much romance and not enough of the tragedy of war.

**The Road to Glory (1936) is not Southern in setting but is a truly epic treatment of French soldiers in World War I. The screenplay is Faulkner’s work and thus part of Southern literature.

James Franco has recently (2013 and 2014) tried to put two of Faulkner’s most difficult works into film: (X) As I Lay Dying and (X) The Sound and The Fury. For once I agree with the respectable critics in finding these attempts entirely unsatisfactory, for multiple reasons. You might call these two films at best comic book versions of Faulkner. You would never know from them why these are great books or understand the depth of Faulkner’s vision.

I do not care for the 1950s Hollywood’s mangling of Faulkner in (X) The Sound and the Fury and (X) The Long Hot Summer. The Hollywood renderings of Faulkner’s Sanctuary, I find mildly interesting but not very recommendable: (T) The Story of Temple Drake (1933) and (T ) Sanctuary (1961).

Faulkner, of course, spent a lot of his talent in Hollywood writing for the screen. Like all Southerners, he needed the money. It is said that once when he had a block on a particular script, the studio head told him to go home and rest. So, he hitched up his horse trailer and headed back to Mississippi. Were Hollywood able to deal honestly with itself, Faulkner’s portrayals of Southern California and Yankees in general would be a true learning experience.

Faulkner’s screenwriting made major contributions to the adaptations of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep (1946) and Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and To Have Not (1944), a Humphrey Bogart vehicle. There are many other good films with Faulkner’s touch. During World War II Faulkner wrote the script for a biography of Charles de Gaulle, but production was forbidden by FDR.

WHAT COULD BE: Imagine if we had a truly Southern film industry or even if Hollywood represented a true national culture (if the U.S. had a real culture). What could be done in transferring the stories of the great Southern writers to film! Not to do so indicates an ignorance of the best part of genuine American culture. Hollywood did alright with Tom Wolfe’s (T) The Right Stuff but made an unholy distorted mess out of his (X) Bonfire of the Vanities. Some of Flannery O’Connor’s short stories have been made into half-hour TV dramas which I have not reviewed. The film attempt at her (X) Wise Blood 1979): skip the movie and just listen to O’Connor’s comments and reading in the Bonus material.

If there were an independent Southern movie industry, Faulkner’s War Between the States novel, The Unvanquished, would be a blockbuster rendering of Southern courage, sacrifice, and honour. And his Go Down, Moses would be a marvelous exploration of a large segment of American life. How about George Garrett’s Elizabethan trilogy, Fred Chappell’s delightful I Am One of You Forever, Andrew Lytle’s Long Night, any of the works of Elizabeth Madox Roberts, Caroline Gordon, Walker Percy? The list could go on almost forever. This would put U.S. film into the world-class category. Instead we have an endless trashy inventory of prequels, sequels, comic book characters, absurd fantasies, obscenity, violence, and stupid, vulgar dehumanizing comedy illustrating the trivial lack of decency and dignity that characterises so much of American life.

______________________________________________________________________________

AFTERWORD

As you know, the folks who dominate the American movie industry regard the South, when they think of us at all, as the weirdest and most dangerous part of that unknown territory between the JFK runways and L.A. International. Besides, Yankees since the 17th century have regularly projected their sins, nightmares and forbidden fantasies onto Dixie.

The South makes up such a large part of the American past and present that it can hardly be ignored. A great deal of what the movies have churned out about us is the usual propagandistic hate and misrepresentation that we are all too familiar with from “news” and “entertainment.” Southerners are most often presented as murderous and stupid hayseeds. So far as American media is concerned that is the nature of the beast.

Being well past my allotted three score and ten, I realise that I have spent too much time watching movies. I can only hope that come judgment a merciful Lord will forgive my frivolous wasted hours. My excuse is that cinema has been, in my time, a powerful influence on the ideas, attitudes, values, and behaviour of a great many people. In earlier days that role was filled by the Bible and the classics. The 19th century was largely dominated by the novel, and for most of the 20th century it was the movies. My chief interest in my wasted hours of diversion has been the strange career of Hollywood in its treatment of the South, America’s Internal Other.

By default a citizen of the United States, I can only feel shame at the condition American mainstream film has reached in the 21st century—pornography, nihilistic violence, imitativeness, moral depravity, and just plain triviality—an entirely post-Christian product. The compulsively filthy language of urban Northerners is now standard everywhere. American film is no longer literature unless comic books qualify as literature. Today’s movie industry is only surpassed in evil influence by its bastard offspring, television. Television is the greatest instrument for lies ever invented. It not only lies with words but also with pictures. And let us remember who is the Father of Lies.

The sense of shame is especially acute when I realize that other countries have maintained some literary and artistic standards in their cinema—Britain, France, Italy, Norway, Poland, Russia, Australia, Japan, and even Iran, a country which our late-Empire American megalomaniacs want to destroy. (Old men are irascible. I generalise too sweepingly about American movies. There are still good ones being produced by good people who have at least one foot out of the Hollywood mainstream.)

The hollow post-Christian post-Western “culture” reflected by Hollywood reflects the truth that there is no “American” culture, unless one counts a talent for gadgetry. If we define culture as creativity working in an authentic tradition, a combination of genius and folk culture, then we have to count “America” out. There are good reasons why every original American form of music has come from the South, as well as a preponderance of our greatest writers. Sorry, Minneapolis, but symphony orchestras with foreign conductors playing European music and museums full of European art bought by wealthy industrialists don’t make the grade. This, as Donald Davidson observed long ago, is “culture poured in from the top,” not the real thing.

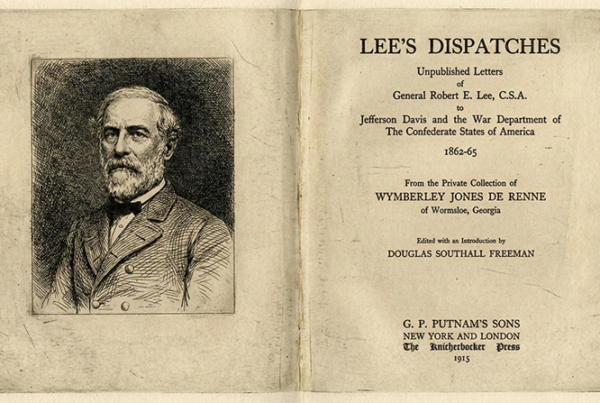

We can be fairly certain that, accompanying a general decline of knowledge in the American public, most people now get their notions of the Old South and the Confederacy from the silly melodrama Roots and Ken Burns’s government-subsidised Radical Republican propaganda piece. Americans are now obsessed with victimology, and “slavery” is now the main theme of our history. This feeds upon the all-too-common American self-righteousness that preens itself on condemning the sins, real or imagined, of others.

As far as cinema is concerned, Southerners are going to have to rely on their own resources for truth-telling. We have a number of advantages in this regard if they can be put to use—abundant talent and the fact that our Confederate and other forebears are intrinsically attractive despite all that has been done of late to libel them.