Each of us tends to be a prisoner of our own experience. In a World with billions of people, we experience only a tiny part. Thus, we rely upon our imaginations to complete a mental picture that results in our “worldview,” meaning our personal conception of the World. Moreover, our imaginations are fed by the narratives we learn from academics, the media, and Hollywood. Too often their stories are corrupted by political correctness. As a result, political correctness is a euphemistic term for mental imprisonment.

When valid, but politically incorrect, ideas are censored our worldview becomes distorted. Unfortunately, political correctness is used as a weapon to impose such mental imprisonment by silencing dissenting voices. Cultural censorship is easily attained with ad hominem attacks using code words such as racist, white nationalist, white supremacist, neo-Confederate, Lost Causer, and even Southerner. Today’s example comes from The New York Times.

Yesterday The Times published an article titled: “What Should Happen to Confederate Statues?” Among its remarks were the following:

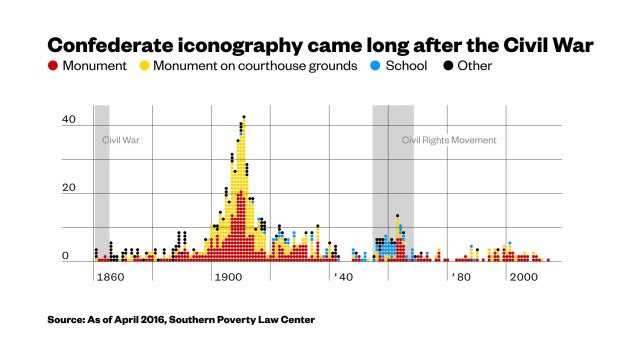

Many Confederate statues being debated today did not originate during the Civil War era, when Southerners built obelisks in cemeteries and other tributes with themes of mourning. The towering figures of individual soldiers and monuments in public squares generally came later, historians say, during the rise of Jim Crow laws and subsequently during a backlash against desegregation.

“That is when you are simultaneously seeing the dedication of these monuments,” said Christy Coleman, the chief executive of the American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Va. “They are not separate things. They are a reassertion of the ideal.”

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) originated that bogus narrative when they released the chart below. While it documents that the vast majority of the “towering figures of individual soldiers and monuments in public squares” were erected between 1900 and 1920, the SPLC falsely attributes the surge to white supremacy and Jim Crow. Only someone mentally imprisoned by political correctness could reach such a conclusion for four reasons.

First, and foremost, the period coincided with the war’s semi-centennial when veterans were dying off. A twenty-one year old who went to war in 1861 was sixty years old in 1900 and eighty in 1920. Second, the same factor caused the number of Union soldier statues erected to swell during the same era. Presumably, Jim Crow and white supremacy cannot explain the Union statue-building. Third, the South was too impoverished for decades after the war to financially afford memorials like those that Northerners had been building for years in honor of their Civil War heroes. Notwithstanding its population growth, the South did not recover to its of pre-war economic activity level until 1900. Fourth, Jim Crow was not isolated to 1900 – 1920. It extended for years on either side of the interval.

When The Times attributes the second minor surge of Confederate monument building during the 1960s to “a backlash against segregation” it overlooks the fact that the early 1960s coincided with the Civil War Centennial. Although the United States Post Office issued five Civil War commemorative stamps between 1961 and 1965, only an imprisoned mind could believe that the Office was motivated by “a backlash against segregation.”