One of the two commandments the Lord Jesus Christ gave to His disciples to follow was to love our neighbor as ourselves. However, in the modern United States of America, we no longer have neighbors. We either have ideological allies; or we have ideological opponents, who keep us from enjoying the right to say or do this or the right to be equal to that. The object of our affection is not men and women made in the image of God but cold, dead, national legalisms, the sharp claws and fangs of the all-devouring god of the Constitution. It is no wonder that the love of many has waxed cold.

Our loyalties have gone all out of order. We need to refocus. We need to contract our sight a bit, from the interstate to the local, from the general to the particular, from the rights of people to people themselves.

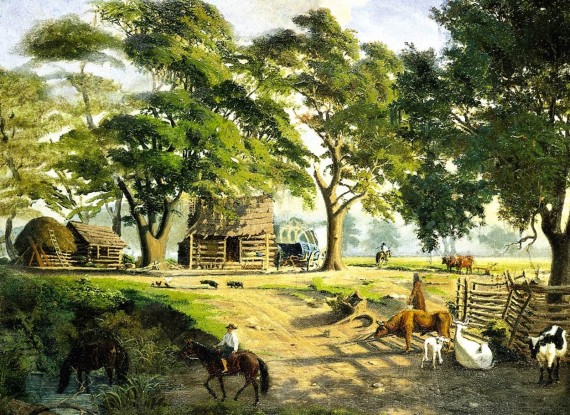

For help in this endeavor, let us turn to colonial Virginia, the cradle of Southern culture, and to her basic social institutions. Prof David H. Fischer describes them for us. One was the vestry of the parish church; the other, the county court:

Both were dominated by self-perpetuating oligarchies of country gentlemen—the parish through its vestry, the county through its court.

About the county court in particular, Prof Fischer writes,

Its principal officers were the county justices, the county sheriff and the county surveyor, who were nominally appointed from above rather than elected from below. In practice they were controlled by the county gentry, who regarded these offices as a species of property which they passed on to one another. . . .

On court days a large part of the county came together in a great gathering which captured both the spirit and substance of Virginia politics. Outside the courthouse, the county standard flew proudly from its flagstaff, and the royal arms of England were emblazoned above the door. The courthouse in Middlesex County actually had two doors which symbolized the structure power in that society—a narrow door at one end of the building for gentry, and a broad double door at the other for ordinary folk. Inside, on a raised platform at one end of the chamber sat the gentlemen-justices, their hats upon their heads, and booted and spurred . . . . To one side sat the jury, “grave and substantial freeholders” who were mostly chosen from the yeomanry of the county. Before them stood a mixed audience who listened raptly to the proceedings. Outside on the dusty road, and peering in through the windows was a motley crowd of hawkers, horse traders, traveling merchants, servants, slaves, women and children—the teeming political underclass of Virginia.

—Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America, Oxford UP, 1989, pgs. 406-7

Here is a community; here are people with a healthy, normal interest in other people as people, not as political objects to be manipulated, not in the political abracadabra of amendments and clauses. They experience the wider communities of State and Mother Land precisely through the county courthouse, through the ‘county standard [flying] proudly from its flagstaff’. Today, we have inverted the order: We experience local life as a little appendage of the national life emanating from Washington City, groveling our thanks that we can be part of the Great Experiment of deluded Puritan messianism and corrupt corporate cronyism.

But the union is too vast and abstract for us to properly love. We must know and love the local, what we can see, touch, hear, taste, and smell. I cannot experience a snowstorm in the Dakotas or the steady rain in the evergreens around Spokane. But I can touch the snowbells growing in my yard in Louisiana, and watch and listen to the creek flowing behind the house.

The county presents a limit for our affections. The average size of a county in the 50 States is about 1,200 square miles. This would make a square of about 35 miles long and wide, with a border length of about 140 miles in all. If a man walked an average pace (3.5 mi/hr) around the border 8 hours a day with no breaks, it would take him no less than 5 days to complete the circuit.

But within that boundary lies an astounding variety of life. Each surname of each family who lives within it contains the deeds of a clan across the generations down into the mythic past (and with an average of about 105,000 people per county, that is quite a lot of history to delve into). The walls of each home have witnessed numerous acts of the human drama – the dark ugliness of sin, the radiant beauty of virtue, the steady rhythms of a normal day – and beheld of the work of the muses: poems, music, songs, paintings. Each church and town has its founding story and first members. Every graveyard and battlefield has numerous tales to share with us. The Indian mounds call us into communion with the first peoples here. The hills, trees, lakes, mosses, rocks, grasses, beasts, flowers, insects, birds, fish, fountains, rivers, caves, and the like each present an inexhaustible source of enjoyment, whether through active observation and exploration or simply by watching and contemplating. It would take, not five days, but five lifetimes to fully appreciate the contents of a single county.

The county is big enough. It is the scheming of insane globalists like Zbigniew Brzezinski to transform us into global citizens that draws our affections away from local life and culture. The Lincolnian nationalists, whether the cruder Limbaugh/Hannity sort or the smooth-talking set at National Review, effect the same end. But the voice of memory, like the piercing utterance of a prophet, cries out to the South, from within the soil, from within our very blood, to repent, to turn away from all such evils:

Before the automobile destroyed the country communities (the Civil War did not) people lived fairly close together without losing their privacy or their family distinctions. The radius of visiting and trading and marrying was generally not more than seven miles [this makes for an area of roughly 150 square miles, much smaller than even the average-sized county of today-W.G.], but seven miles at a walk or even in a buggy takes time. You just didn’t drop in for a chat. You spent the day at least. And the railroads did not disrupt these communities; they merely connected them. Conversation reached a high art, and it generally talked about what most interested itself, and this was the endless complications within the family and what gossip or rumor hinted at in the neighbors. Every human possibility was involved, including politics, but the blood lines were the measure of behavior.

–Andrew Lytle, Foreword to Stories: Alchemy and others, University of the South, 1984, pgs. xviii-xix

The little community is the touchstone in the South, not the great girth of the national leviathan. Dixie does not need the ideologies that issue from Washington City (whether of the ‘Left’ or of the ‘Right’) or every new gadget that comes from the bowels of MIT and Silicon Valley; just the Church, the family, the county courthouse, and the other places where normal human interaction takes place. Most of the weighty matters of life should be discussed and decided in them firstly. But does the South still have ears to hear the pleading voices of her past?