A review of Bust Hell Wide Open: the Life of Nathan Bedford Forrest by Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., Regnery History, 2016.

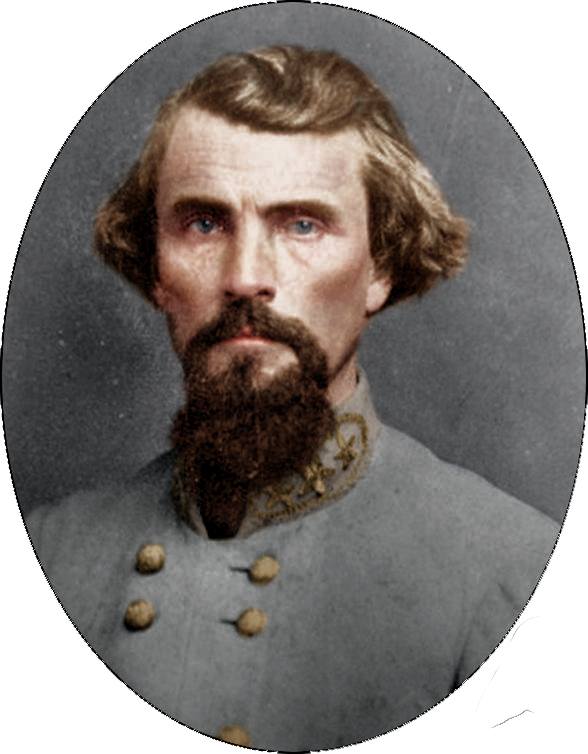

Writing a biography about Nathan Bedford Forrest – a man recognized by no less than General Robert E. Lee and General William T. Sherman as “the most remarkable man produced by the Civil War on either side” – is a daunting task. How does an author do justice to such an imposing historical figure? In Bust Hell Wide Open: The Life of Nathan Bedford Forrest (Regnery History, 2016), author Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr. proves that he is more than up to the challenge. Unlike many biographies, which can get so mired in minutiae that reading them feels like a forced march, Bust Hell Wide Open reads like a rollicking cavalry charge. Perhaps most importantly for a figure as controversial as Forrest, Mitcham massacres the untruths and misperceptions that have haunted him and unjustly darkened his legacy. Mitcham’s Bust Hell Wide Open can ride in the company of Forrest classics such as John Allan Wyeth’s That Devil Forrest, Andrew Nelson Lytle’s Bedford Forrest and his Critter Company, and Robert Selph Henry’s First With the Most.

There are many historical figures whose early lives give no indication of future greatness. Who would have thought that the corporate attorney and Illinois politico whose biggest accomplishment was getting trounced by Stephen A. Douglas would become the messianic President who “saved the Union” and “freed the slaves,” Abraham Lincoln? Or that the quiet, dignified officer from Virginia who seemed to have reached his peak in the Mexican War would become a military genius who turned the tide of the Civil War and a symbol of pride and hope to Southerners ever since, Robert E. Lee? There was never any doubt that Forrest was destined for greatness, however. Even from his humble roots in the Tennessee and Mississippi backcountry, Mitcham shows how every signature characteristic of the “Wizard of the Saddle” was already there in spades: his chivalry (placing himself between lynch mobs and their victims), his bravery (leaping into fights no matter the odds), his determination (hunting and killing any beast or man which threatened him or his own), and his trickery (bluffing bigger, stronger enemies into backing down). Indeed, at a phrenological lecture, Forrest even had his head measured, and was pronounced “a man who would have been a Caesar, a Hannibal, a Napoleon if he had the opportunity.” According to the phrenologist, “If he could not go over the Alps he would go through them.”

Mitcham does not sacrifice Forrest to the wrathful volcano god of American history – slavery. Indeed, it is impossible to appreciate Forrest (or anything Confederate, for that matter) if you feel intense shame or sanctimony over slavery. Outside of Muslim fanatics who purge any remnant of their pagan, pre-Islamic past, no other people in the world are as self-hating or self-righteous about their history as Americans. Until the 1960s, when Marxist-Leninists replaced Klassenkampf (class war) with Kulturkampf (culture war) and mass-immigration created a fifth column of Third-Worlders, Americans mourned the Civil War as a national tragedy and honored both sides. Today, however, “equality” has become like the Ring of Power in the hands of our political, intellectual, cultural, and corporate elite – the one ring to rule them all – and thus anyone or anything tainted by slavery must be purged.

Mitcham does not sugarcoat the fact that Forrest was a slave trader and a slave owner. “Forrest’s world view was that of a nineteenth-century Southerner…and a man who grew to manhood in the raw, tough, and often violent world of the antebellum American frontier,” writes Mitcham. “I hold that we can learn a great deal from the past and from the people who populated it, people like Forrest, even though we might not want them as neighbors.” Starting with an inheritance of several slaves from his uncle, Forrest built a large, lucrative slave-trading business. Although slave trading – trafficking in human property – was a fundamentally inhuman business, Forrest was, as Mitcham puts it, “the best of a bad lot.” Forrest not only never sold family members off separately, but also went out of his way to reunite families who had been separated. Far from treating his slaves like animals in “pens,” Forrest kept them sheltered, fed, clothed, and healthy, and never beat or whipped any of them. Forrest even encouraged his slaves to read (a crime in many States) and allowed them to go into town by themselves and seek out their own masters. Eventually, Forrest transitioned out of the disreputable slave trade and made himself respectable: he acquired several large plantations in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Arkansas (worked by over 200 slaves) and was even elected as a Memphis alderman. Later, when Forrest rode off to war, he took all 43 of his adult male slaves with him, promising to reward loyal service with personal freedom. Forrest ended up freeing them early, however, in case he was killed before the war ended. At least twenty of his former slaves followed him home and worked on his plantations as freedmen. “Those boys stuck with me,” recalled Forrest of his black soldiers. “Better Confederates never lived.”

Like most Southerners, Forrest was a “Union man,” meaning that while he supported States’ rights he did not support the extremity of secession. Forrest, along with a majority of Tennesseans, Virginians, North Carolinians, and Arkansans, originally voted against his State’s secession referendum. Also like most Southerners, President Lincoln’s declaration of war on the Confederacy and assembly of an invasion force completely changed Forrest’s mind; Forrest and other “Union men” soon after voted secede in solidarity with their Southern brethren. Although a well-off and well-respected man, Forrest initially enlisted as a private in the Tennessee cavalry. Tennessee Governor Isham G. Harris, however, shocked by Forrest’s humility, gave him a promotion and authorized him to raise a cavalry battalion of his own – which he did, out of his own pocket. Forrest’s ascent from private to lieutenant general was the single biggest rise through the ranks of any man during the war.

In battle, Forrest would become, as one Confederate put it, “the very God of War.” His face would darken as it flushed with blood; his blue eyes would blaze with intensity; his low drawl would become a tiger’s roar. His feats on the battlefield – dodging bullets left and right, cutting heads clean off, and “charging both ways” – sound more Homeric than historic. For example, at Memphis, Forrest dueled a Yankee champion in single combat to decide the fate of their commands, just like Hector and Achilles at Troy. Even Forrest’s favorite warhorse, “King Phillip,” would fight for him, trampling, kicking, and biting anything in Yankee blue. Indeed, the tales of Forrest’s martial prowess would defy belief, if they were not repeated again and again by Yankees as well as Confederates.

Mitcham, a former soldier and experienced military historian, describes every one of Forrest’s battles with competence and clarity. Mitcham wisely uses Forrest’s very first battle at Sacramento, Kentucky, as a demonstration:

“At Sacramento, the standard tactics that Forrest would apply during the war made their debut. Field Marshal Viscount Wolseley noted that ‘his methods were the common sense tactics of the hunter and Western pioneer.’

“1) He always outflanked the enemy on both flanks and got into his rear, creating disorganization and sowing confusion in enemy ranks.

“2) At the first sign of confusion on the enemy’s part, he always attacked.

“3) He almost always attacked with everything he had and never left anything in reserve…

“4) He often used his cavalry as mounted infantry, meaning that his men would ride to the battlefield, and then attack as infantry.

“5) He almost always led from the front, inspiring his men by his example. His personal courage was remarkable, astonishing friend and foe alike. He had nothing but contempt for those who feared danger.

“6) He never met a charge standing still. He instinctively understood the psychological disadvantage of waiting for an attack. If the Yankees attacked first, he always met them halfway. ‘Never stand and take a charge,’ he once exclaimed. ‘Charge them too!’

“7) He trusted his own instincts. ‘Forrest seemed to know by instinct what was necessary to do,’ Captain James Dinkins recalled.

“8) He generally treated his prisoners well. ‘He fought to kill but he treated his prisoners with all the consideration in his power,’ Dinkins recalled. ‘So did his own men.’

“9) He was always the aggressor.

“10) He always did what the enemy least expected.

“Finally, fighting seems to have excited him.”

Using Sacramento as a demonstration, Mitcham makes the rest of Forrest’s many battles easier to follow and remember.

While the average American almost certainly knows nothing about Forrest’s victories at Okolona and Brice’s Crossroads (battles later studied by Viscount Wolseley, Lord Wavell, Ferdinand Foch, and Erwin Rommel for their brilliance), the one battle he may know is the so-called “Fort Pillow Massacre.”

In a video from The Blaze, Glenn Beck and pseudo-historian David Barton (both of whom make their living peddling fake history to gullible American evangelicals) took the lies about Forrest and Fort Pillow from the realm of ignorance to idiocy. Beck referred to Fort Pillow as “a massacre of Biblical proportions” and Forrest as “a really, really evil guy.” Barton chimed in that Forrest actually ordered black soldiers flayed alive and nailed to the sides of barns. Beck then held up what he claimed was Forrest’s saber – “a sword of tremendous American evil” – which Barton told him was probably used to flay blacks alive and supposedly gave filmmaker Ken Burns the willies. If Beck were a good Mormon, then he would know how stupid it is to compare the alleged slaughter of a few surrendering soldiers to God wiping out entire civilizations with floods, pillars of fire, and plagues. If Barton were a legitimate historian, then he would know not to take at face value every newspaper “report” during the War, which abounded with fake news. If Beck and Barton had ever so much as peeled an orange, they would know that the notion of flaying a live human being with a saber is ludicrous. For those of us who do not get our history from the likes of Beck and Barton, Mitcham dispassionately presents what actually happened at Fort Pillow.

Forrest was on his way to Mississippi, but was enjoined by local Tennesseans to put an end to the raiding from Fort Pillow. The Yankee garrison was comprised of Tennessee Unionists and U.S. Colored Troops (notorious for thieving, burning, raping, and murdering) with unscrupulous and incompetent leadership. After a long, hard day of heavy fighting, with repeated refusals of surrender and even taunts from the Yankees, the Confederates finally stormed the fort’s innermost defenses. Because the Yankee commander panicked and fled, leaving his men leaderless, the fort was never officially surrendered, meaning that the fighting and killing went on much longer than it should have. To be sure, there were reports of Confederate soldiers, in the heat of battle, cutting down defenseless Yankees (especially Colored soldiers) in cold blood. There were also reports of Colored soldiers throwing down their weapons and surrendering to the Confederates, only to shoot them in the back at the first opportunity. Upon entering the fort, Forrest ordered a ceasefire, and soon after Yankee prisoners were tending to their wounded and burying their dead. Some massacre!

Out of the 557 Yankees at Fort Pillow, 277-297 were killed and 226 were captured (168 white and 58 black). How many of these were killed during the fighting versus after the fighting is unknown. These casualty rates were high by Civil-War standards, but they do not meet the definition of a “massacre,” which is the total destruction of a defending force (e.g. Thermopylae and the Alamo). The high casualty rate can be explained, in large part, by the cowardice and incompetence of the Yankee commander, who ran away without surrendering the fort and forced both sides to fight to the bitter end. The slaughtering of surrendering soldiers was an atrocity, but that does not mean that the battle was a “massacre.” Even then, when Forrest entered the fort he did not allow any “massacre” to continue, but showed mercy to the Yankees. Forrest could have wiped out every last living Yankee at Fort Pillow, but instead he let many live; this cannot, by definition, be a “massacre.” Last, but not least, there is no comparison between whatever happened at Fort Pillow and the plundering, burning, raping, and murdering to which the Yankees subjected the Confederate civil population wherever they went.

After Fort Pillow, the rest of Forrest’s modern-day infamy comes from his postbellum life, particularly his leadership of the Ku Klux Klan. “Now, it is a fact that it was a Democratic delegate to the Democratic National Convention, Nathan Bedford Forrest, who founded the Ku Klux Klan,” claimed the pundit Dinesh D’Souza in an interview with the talk-show personality Rush Limbaugh. “It is also a fact – and here I’m quoting the progressive historian Eric Foner – that for 30 years the Ku Klux Klan was the domestic terrorist arm of the Democratic Party in this country.” Regarding the silly argument that the Klan and the modern Democratic Party have anything to do with one another, Mitcham simply comments, “Organizations often change over time.” Regarding Forrest’s role in the Klan and the Democratic Party, Mitcham corrects the untruths while also adding vital historical context.

Forrest did not found the Klan; it was founded by a group of Confederate cavalry veterans as a club for drinking and gambling. “Ku Klux” was a corruption of the Greek word “kuklos” (i.e. “circle,” as in “social circle”), and “Klan” was added for alliterative effect. It was only when Reconstruction took a militant turn – with Republicans calling for a “second civil war” against the defeated Southern whites – that the Klan became a paramilitary force, donning hoods for anonymity and riding out at night to terrorize “Carpetbaggers” (Northern opportunists), “Scalawags” (Southern Unionists collaborating with the Yankees), and freedmen (emancipated slaves bloc-voting for the Republicans). When a delegation of Klansmen (led by former Confederate General John B. Gordon) paid Robert E. Lee a visit and asked him to assume command of the Klan, Lee declined due to his weak health, but wrote Forrest a letter recommending him for the position. Forrest accepted and became the first “Grand Wizard” of the Ku Klux Klan – a reference to his wartime moniker as “Wizard of the Saddle.”

William G. “Parson” Brownlow was a Tennessee Unionist who did not discriminate between black Africans and white Southerners; he hated both equally. After the war, Brownlow was elected Tennessee Governor in an election in which only other white Unionists were allowed to vote. Of Southern whites Governor Brownlow decreed, “Let them be exterminated,” and called on the federal government to “make the entire South as God formed the earth, without form or void.” In turn, Forrest responded, “If they bring this war upon us, there is one thing I will tell you – that I shall not shoot any negroes so long as I can see a white Radical to shoot, for it is the Radicals who will be to blame for bringing on this war.” When Brownlow went to the U.S. Senate and Clinton DeWitt Senter (a more moderate Tennessee Unionist) took his place as Governor, Senter ceased his predecessor’s apocalyptic threats, disbanded the militia, and promised to restore suffrage to former Confederates. Forrest considered the Klan’s mission accomplished and ordered its disbandment. “There was no further need for it,” he explained. “The country was safe.”

Mitcham also addresses one of the most tantalizing “what ifs” of the War: What if, in the summer and autumn of 1864, Confederate President Jefferson Davis had allowed Forrest to raid the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad supplying General William T. Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign? General Joseph E. Johnston was defending Atlanta against Sherman, and although his Fabian plan of strategic retreats had been effective at delaying the inevitable, he knew that he could not hold out forever. At the time, with seeming stalemates along the two major fronts in Atlanta and Richmond, the war was not going well for the Yankees, and Republicans as high up as President Lincoln himself expected to lose the coming elections to the anti-war Democrats. To that end, Johnston, along with his two senior corps commanders Leonidas Polk and William J. Hardee, requested that Davis allow Forrest to raid Sherman’s supply lines. With Forrest in his rear cutting off his supplies, Sherman would either have to weaken his army by detaching soldiers to stop Forrest or cancel the campaign altogether. General Stephen D. Lee, Forrest’s department commander, agreed with Johnston, Polk, and Hardee. Tennessee Senator Gustavus Adolphus Henry, Georgia Senator Benjamin H. Hill, Georgia Governor Joseph E. Brown, and former Georgia Governor Thomas Howell Cobb all tried to persuade Davis, but to no avail. Under the advice of General Braxton Bragg, who hated Forrest for petty personal reasons, Davis was convinced that Forrest was a mere “partisan” and denied the request. As a result, 473 miles of undefended railroad were left open, Atlanta was captured and burned by Sherman, Lincoln, Lincoln and the Republicans were reelected, and the fate of the Confederacy was sealed. After the War, Forrest and Sherman happened to encounter one another on a steamboat. “Most of the exchange between them remained private, but Sherman was overheard telling Forrest that, before and during the Atlanta campaign of 1864, he not only filled Sherman’s every waking moment, but occupied his dreams as well,” writes Mitcham. “Forrest replied that, if Richmond had given him the command he asked for, he would have turned Sherman’s nightmares into reality.”

Forrest was buried with his wife in Memphis’ Elmwood Cemetery. His funeral procession stretched for three miles and was attended by 20,000 mourners, 3,000 to 6,000 of whom were black. The current Tennessee Governor James D. Porter and former Confederate President Jefferson Davis rode behind Forrest’s hearse. “History has accorded General Forrest the first place as a cavalry leader in the War Between the States, and has named him as one of the half-dozen great soldiers of the country,” Porter told Davis. “I agree with you,” replied Davis. “I was misled…I saw it all after it was too late.”

Forrest and his wife now rest in a park in downtown Memphis. Atop their graves stands an impressive statue of Forrest astride King Phillip. In the summer of 2015, however, the Memphis City Council, as part of a nationwide anti-white backlash over a rare incident of white-on-black crime in Charleston, voted to tear down the statue and dig up both graves. Vandals spray-painted the statue with “Black Lives Matter” graffiti and attacked the gravesites with a shovel. Fortunately, the Tennessee Historical Commission managed to block this ghoulish plan, but as long as the Left rules the country’s political, cultural, and economic institutions, such victories will be nothing more than the last light before nightfall. For instance, despite massive popular opposition, the municipal government of New Orleans has given in to the demands of outside pressure groups and is poised to topple old statues of Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and P.G.T. Beauregard. To turn back the coming darkness of “political correctness,” we need more historians with the perspective of Mitcham, writing not from the present looking backward, but from the past looking forward.