In 1957, Senator John F. Kennedy issued a report on the five most important Senators in United States history. He included John C. Calhoun, and while he understood the historical controversy it might create, Kennedy insisted that Calhoun’s “masterful” defense “of the rights of a political minority against the dangers of an unchecked majority” and “his profoundly penetrating and original understanding of the social bases of government” outweighed any negative assessments of his life and career, arguing that “the ultimate tragedy of his final cause neither detracts from the greatness of his leadership nor tarnishes his efforts to avert bloodshed.” Kennedy concluded that Calhoun “significantly shaped the role of the Senate and the destiny of the nation.”

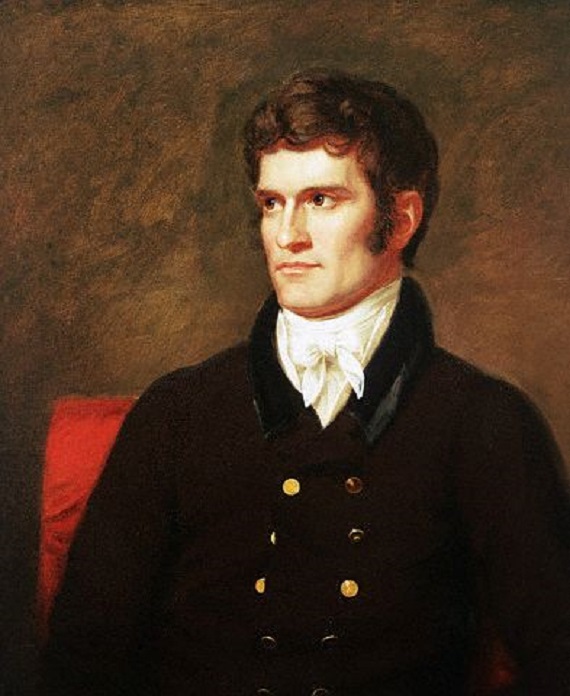

Kennedy was undoubtedly influenced by fellow New Englander Margaret Coit’s 1950 Pulitzer Prize winning biography of Calhoun. Coit’s portrayal of Calhoun was not only sympathetic–while still in school in the 1930s, Coit thought Calhoun to be “heroic”–it supported a revival of popular interest in the great South Carolinian. Coit bucked the trend by establishment historians to reduce Calhoun to a simplistic “defender of slavery” and the stern, cast-iron intellectual father of the Confederacy. Coit’s Calhoun was a warm, charming, and funny statesman who as a young man dined with Jefferson and as an old man attempted to keep sectional peace. Coit replaced the mainstream perception of Calhoun of the hollowed out walking skeleton of his later years due to the effects of tuberculous, an image of the very devil incarnate as some contemporaries described him, with the handsome and brilliant man with a warm smile and unassuming countenance shown in earlier portraits.

Kennedy’s description of Calhoun also matched that of Russell Kirk in his seminal The Conservative Mind, published in 1955. Kirk considered Calhoun to be one of the great conservative thinkers in American history. Kirk admired Calhoun and the Southern tradition for its rigid adherence to federalism and its attacks on scheming centralization. Like Kirk, Kennedy could separate Calhoun’s defense of slavery from his important contributions to American society.

Much has changed since 1957. By the 1970s, academic historians had again reduced Calhoun to little more than a fanatic or a lunatic at best, and a proto-Nazi at worst. Apparently, every word he spoke veiled a defense of slavery and racism, an argument that dated to one of the earliest biographies on Calhoun by H. Von Holst. Like the Radical Republicans of the mid-nineteenth century, Holst believed that slavery undergirded every argument Southerners made in antebellum period, from tariffs to their interpretation of the Constitution. These simplistic descriptions of the American past passed for serious scholarship and advanced careers, even to this day. For example, a recent book by the Princeton historian and poser working man Matthew Karp, This Vast Southern Empire, regurgitates the “slave power” thesis of the 1850s sprinkled with a bit of Samuel Flagg Bemis’s “Defender of Slavery” description of the decrepit Calhoun. To Karp, Calhoun’s public opposition to the war with Mexico in the 1840s was little more than a charade. In short, Calhoun lied.

Even “conservatives” began piling on, primarily because Calhoun’s desire to protect minorities from abuse by numerical majorities led some leftist thinkers to adopt his views on the “concurrent majority.” This led to an epiphany by American “conservatives.” What if equality was really a “conservative”position? And what if we could turn the staunch Democrat Calhoun, the recognized “defender of slavery”, into a progressive and merge progressivism with slavery and treason? The Radical Republicans did just that in the 1860s, so why not champion the Republican Party as the true party of freedom, liberty, and democracy?

Victor Davis Hanson, Yoram Hazony, Michael Anton, Larry Arn, and a host of other modern “conservatives” have cast Calhoun as the real villain in American society, the heretical outlier in the push for the realization of the “proposition nation.” America had always been the shining city upon a hill, and even if Southerners had corrupted some of her past, right thinking Northerners were always there to bail out the United States and right the ship.

The most recent biography of Calhoun, Robert Elder’s Calhoun: American Heretic, incorporates various elements of these schools into a thorough analysis of the man, but the results are the same. Elder concludes that Calhoun was not a political “heretic” as conservatives claim. After all, his insistence the America was for the “white man” was an uncontroversial point during his lifetime and reflected the general sentiment of most Americans, North and South, but he also insists that we can draw a “strait line” from Calhoun to Dylan Roof’s murderous rampage in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015. He concludes by saying no one should admire Calhoun, and though we would like to forget him, his powerful figure will always be an important part of American history.

Elder made a fatal mistake while scribbling his tome, one that most will miss. He acknowledged the editing work of the greatest living Calhoun scholar, Clyde Wilson, but ignored everything Wilson had to say about Calhoun. Wilson’s seventeen introductions to the Calhoun Papers could be complied into a thorough political biography, and his dozens of essays on Calhoun in both popular and scholarly works and lectures on the man are better than anything modern academics have produced, including Elder, which is what led Shotwell Publishing to publish a collection of Wilson’s essays on Calhoun, Calhoun: A Statesman for the 21st Century.

To Wilson, Calhoun is and was an indispensable statesman. As he said in 1986, “For some years in the vital middle period of American history he carried out this role (the flywheel keeping the Union from fragmenting) successfully in a way that has no precedents or successors in American history.” He covers all aspects of Calhoun’s political life, from his views on economics and foreign policy, to his infamous “positive good” speech, and his arguments on the concurrent majority and nullification. Wilson argues Calhoun can still be a vital voice in twenty-first century American politics. This would not earn a tenure track position at any modern university, but a careful reading of Calhoun shorn from the lens of presentism would lead to the same conclusion by any honest scholar.

I doubt many academics will read the book, a real tragedy due to Wilson’s decades of work on the Calhoun papers and his deep understanding of Calhoun, but that says more about the modern academy than the work itself. Had Wilson produced this book in the 1950s, he would have been praised as a serious contributor to Calhoun scholarship. As it now stands, he, like Calhoun, is nothing more than a political “heretic.” Perhaps that is for the best. These two venerable Carolinians, one a Tar Heel, the other a son of the Palmetto State, will always be joined by their decades together and their belief that statesmanship requires saying what is right even when it is either politically or academically unpopular.

Note: The views expressed on abbevilleinstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.

One Comment