Not long ago, California governor Gavin Newsom condemned President Trump’s nationalization of California’s National Guard units, characterizing it as an attempt “to usurp state authority and resources.” Newsom went on to accuse Trump of “inflaming fear in the community, inciting fear and violence, and endangering state sovereignty.” While nationalist-leaning conservatives are quick to compare the governor to Jefferson Davis, the rest of us might be forgiven for doubting the sincerity of Newsom’s states’ rights rhetoric, and cannot help wondering if the only reason he momentarily questions federal power is because his party no longer controls it. Newsom certainly never applauded the Dobbs decision, which returned the abortion issue to state legislatures and repudiated the federal overreach of Roe v. Wade. Indeed, even with respect to immigration, it was not so long ago that the roles were reversed, with Texas governor and border control “hawk” Greg Abbott defying the Biden Administration by asserting control over the border town of Eagle Pass.

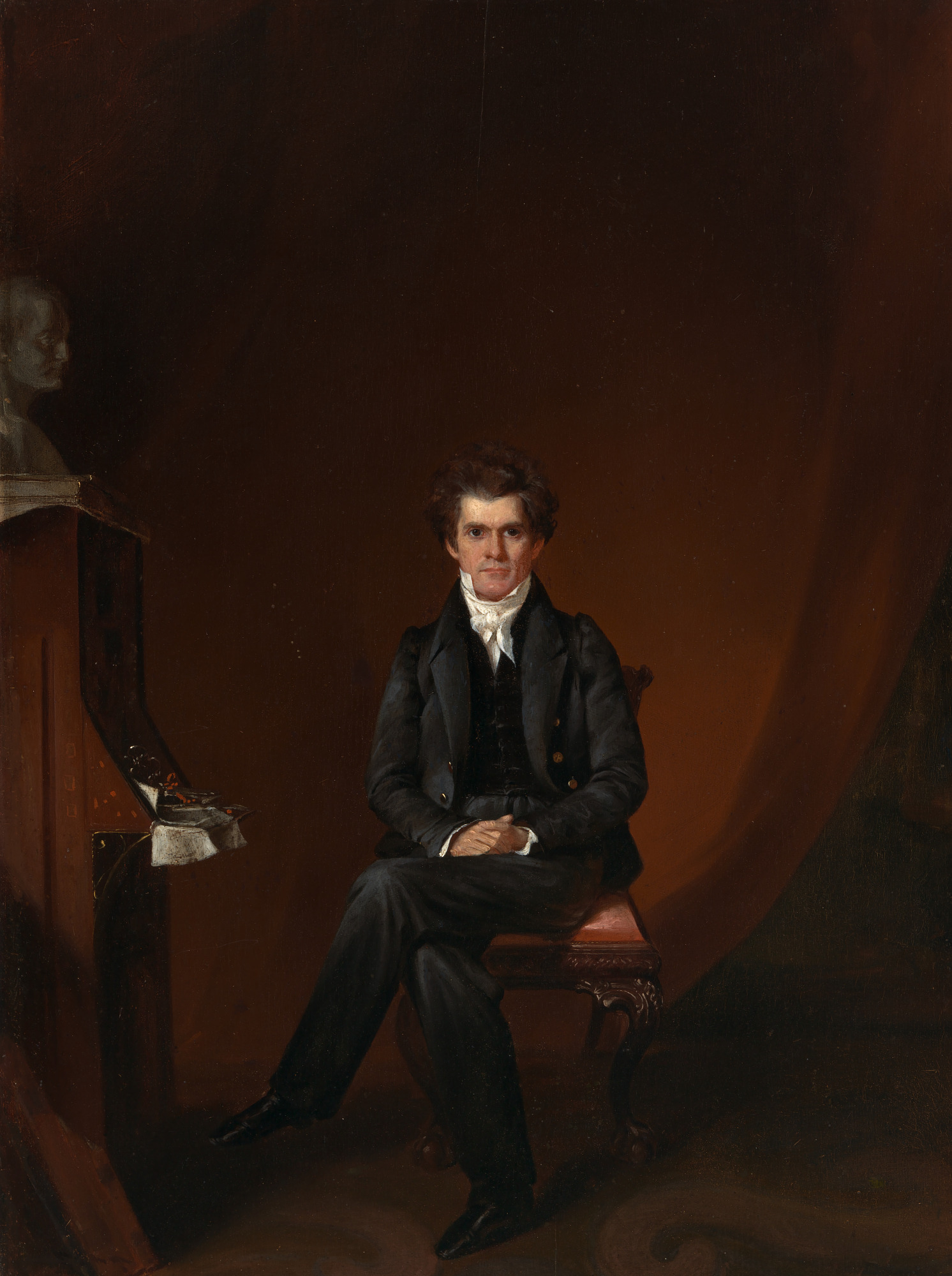

If we wish to think deeply and seriously about federalism, it is best to take a step back from the heated controversies of our day and consider original sources. Ideally, someone might gift governors Newsom and Abbott – and the US Supreme Court – copies of the slender and portable new Imperium Press edition of John C. Calhoun’s A Disquisition on Government. Calhoun was not only one of the most original of American political thinkers, but from an American conservative standpoint he was inescapably “one of us,” insofar as he expresses some of the central tenets of conservative thought.

For instance, he explicitly denounces Rousseau’s conception of the abstract individual in a state of nature. To the contrary, Calhoun declares, man’s “natural state is the social and political – the one for which his Creator made him.” Enlightenment anthropology is debunked by the plain fact that all men “are born subject, not only to parental authority, but to the laws and institutions of the country where born and under whose protection they first draw breath.” Quite aside from the enormously important point Calhoun has made here about the human condition, it is worth noting that he has also rather neatly summed up what conservatism is. Beginning with Edmund Burke, conservatives have always emphasized that we are enmeshed in inherent obligations, debts, and communal interconnections; whether they are right or wrong, those who cry that “man is born free, yet everywhere he is in chains” are, by definition, on the left.

In contrast to the egalitarian leviathan envisioned by utopians, Calhoun aspired toward a decidedly organic republic, one which required the careful cultivation of Anglo-American institutions and practices. Various forms, restraints, and structures would necessarily channel popular forces. Yet Calhoun realized all too well well that the masses see republican government as a simple arithmetical matter of counting heads: “The restrictions which organism imposes on the will of the numerical majority” are seen by would-be reformers as “restrictions on the will of the people,” he pointed out, “and, therefore, as not only useless but wrongful and undemocratic. And hence they endeavor to destroy organism under the delusive hope of making government more democratic.” In practice, Calhoun believed, “more democratic” meant the kind of system we might today call totalitarian.

He furthermore predicted that, barring radical measures, this decay of constitutional barriers was inevitable. Those seeking to expand the role of government and discover new rights through a “liberal construction” of the constitution would be pitted against those defending “a strict construction of the constitution – that is, a constitution which would confine these powers to the narrowest limits which the meaning of the words used in the grant would admit.”

It would then be construction against construction – the one to contract and the other to enlarge the powers of the government to the utmost. But of what possible avail could the strict construction of the minor party be, against the liberal interpretation of the major, when the one would have all the powers of the government to carry its construction into effect and the other be deprived of all means of enforcing its construction? In a contest so unequal, the result would not be doubtful. The party in favor of the restrictions would be overpowered.

Here we may note that Calhoun not only predicted the archetypal conservative judicial strategy of “originalism,” with which he sympathized, but also explained why originalism could at best only slow the long march of the levelers. The real obstacle to an inhuman consolidation lay in alternative centers of power capable of pushback – e.g., robust state governments, independent labor unions, strong church communities.

Of course, friends of the Abbeville Institute know all too well that Calhoun’s name has long since been “canceled” due to his association with slavery, and that the ambiguities, historical context, and nuance of his position have been tossed down the memory-hole, along with his emphatic and explicit insistence that he had never defended slavery per se. Today nothing is left of this once widely-honored American legacy but the cartoonish image of a villainous “enslaver,” to use the fashionable leftist jargon which has such influence over Conservative, Inc. pundits. Real conservatives can distinguish separate issues, and make distinctions in spite of the shibboleths of politically-correct liberal discourse; for the most part, of course, such conservatives are not welcome at Fox News.

After all, we are far removed from the days of Ronald Reagan’s Executive Order 12612, which frankly proclaimed that “our political liberties are best assured by limiting the size and scope of the national government.” In the very same order, Reagan elaborated a vision of federalism utterly antithetical to consolidated nationalism:

The people of the States created the national government when they delegated to it those enumerated governmental powers relating to matters beyond the competence of the individual States. All other sovereign powers, save those expressly prohibited the States by the Constitution, are reserved to the States or to the people. The constitutional relationship among sovereign governments, State and national, is formalized in and protected by the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution.

“Sovereign governments, State and national” – the honorable senator from South Carolina could not have said it better himself. What neoconservatives demonstrate by attacking Calhoun is not that states’ rights doctrine can be dismissed as the wicked legacy of “enslavers,” but that they themselves have no interest in reckoning honestly either with the Constitution, or with the recent history of their own Republican Party.

The views expressed at AbbevilleInstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.

“…but that they themselves have no interest in reckoning honestly either with the Constitution, or with the recent history of their own Republican Party.”

The best in the last.

Excellent work Mr. Jerry. With the exception of a few months during 1948, paleo-conservatives have been without a party for 120+ years.