For five days in May, 1856, Charles Sumner delivered a speech entitled The Crime Against Kansas. For those five days, he continuously slandered South Carolina and its senator, Pierce Butler. Regarding South Carolina, Sumner stated:

“If we glance at special achievements, it will be difficult to find anything in the history of South Carolina which presents so much of heroic spirit in an heroic cause as appears in that repulse of the Missouri invaders by the beleaguered town of Lawrence, where even the women gave their effective efforts to freedom…Already, in Lawrence alone, there are newspapers and schools, including a high school, and throughout this infant Territory there is more mature scholarship far, in proportion to its inhabitants than in all South Carolina.”

This speech was obviously meant to agitate the already widespread feelings of sectionalism. South Carolina was where the American Revolution was basically won through partisan warfare, but maybe that just wasn’t heroic enough for Sumner. In addition, Sumner was quick to ignore the fact that his good friend, John Brown, was murdering people in Kansas around the exact same time as his speech. But Sumner did not stop there, he called Stephen Douglass, the eventual 1860 Democrat presidential candidate, a “noise-some, squat, and nameless animal . . . not a proper model for an American senator.”

Next, Sumner moved on to senator Pierce Butler. Sumner attacked Butler’s honor and mocked his chivalry, saying that Butler had taken on “a mistress . . . who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight—I mean, the harlot, slavery.” Basically, Sumner had called Butler a pimp for the prostitute of slavery.

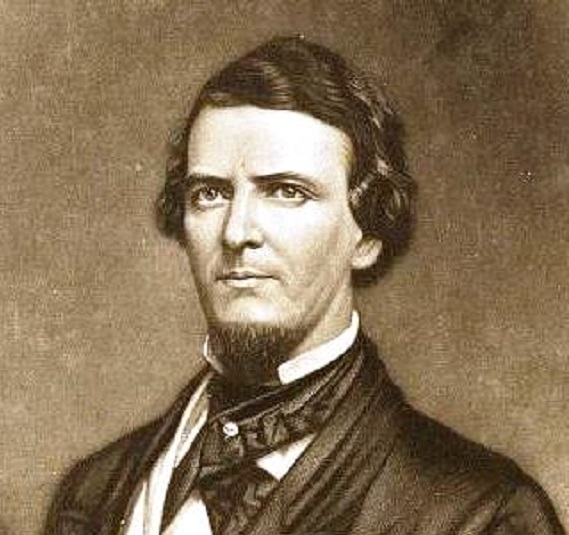

Preston Brooks, the cousin of Pierce Butler, had been present during the Crimes Against Kansas speech and took offense to the slander of his state and kin. Two days after the speech, Brooks decided to strike Sumner with a light cane of the type used to typically discipline dogs. While dueling was still a viable option in 1856, Brooks did not see Sumner as a gentleman and therefore decided against challenging him.

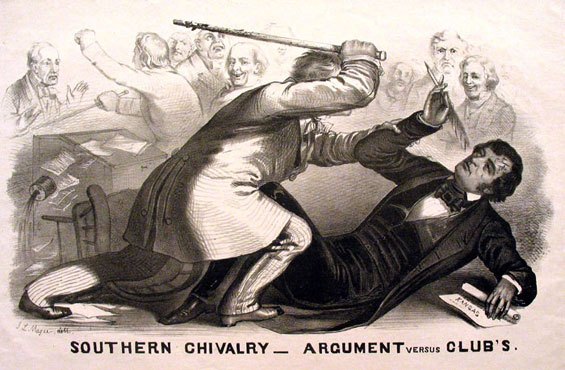

This caning is typically seen as an event that led to the “Civil War,” with Brooks portrayed as a savage. Cartoons of the time that depict the event had captions like “Southern Chivalry: Arguments vs. Clubs” and “The Symbol of the North is the Pen; The Symbol of the South is the Bludgeon.” In reality, Sumner’s speech probably created more division than Brooks’ caning. Butler received canes from Democrats and southerners all over that supported his actions. There is even an urban legend that the Caroliniana library at the University of South Carolina has a spiral staircase made from the canes received by Brooks. At the very least, the library contains a plaque in his honor.

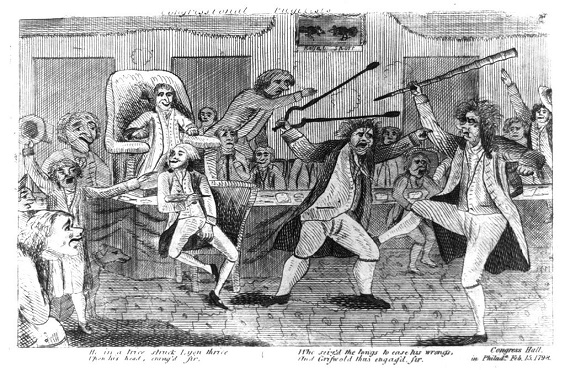

The north was just as guilty of these sorts of incidents. In 1798, two yankee representatives got into a vicious fight on the House floor. Representative Roger Griswold of Connecticut attacked Matthew Lyon of Vermont repeatedly with a wooden cane. To defend himself, Matthew Lyon grabbed a pair of fire tongs and the two had to be separated by the other representatives. The event had stemmed from petty events; Griswold mocked Lyon’s Revolutionary War service, and Lyon had responded by pelting Griswold with tobacco juice spit. Cartoons at the time depicted the event as a “royal sport,” while the men themselves were dubbed “congressional pugilists.” Griswold was a Federalist, and Lyon a Democratic Republican. Lyon had been critical of Federalists like Alexander Hamilton and John Adams, and was one of the first people jailed under the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Notice the portrayals of cane fighting, north and south. In the top picture, the northerners look playful and are labeled “congressional pugilists.” While Brooks (southerner) is portrayed as savage and beating a helpless and limp-wristed Sumner.

This is the difference between southerners and northerners when it comes to cane fighting. Yankees like Griswold and Lyon fought over petty squabbles and political rivalries. Southerners had long taken the political insults of being lazy, racist, and backward. But when Charles Sumner attacked Brooks’ family, the line was crossed. This is because for southerners, honor is a connection of the public and private self. Sumner had not only attacked the very public where Brooks lived, but also slandered his family and inserted his ego into Brooks’ private realm.

Southerners and northerners simply have different ideas of family. The word family comes from the Latin word famulus, which originally meant “servant.” Its first meaning in English was similar to our modern idea of the word “household” and included individuals, servants, and blood relations living under the same roof. Eventually, family came to mean anyone who could claim common ancestry, while in modern society it has come to be considered as one’s immediate kin.

Southerners identified with the old world understanding of family and have long considered it to be of utmost importance. Kith, kin, and (arguably) even slaves were all considered family and served essential roles in the south. To southerners, family was not just a bloodline but a reflection of themselves in the most primeval sense.

When we look at cane fighting in American history, the Griswold-Lyon affair is often overlooked. It shows the hypocrisy with which most people view history. Nobody cares about why two Yankees fought in congress in 1798. But when a southerner attacked a northerner in 1856, most people assume it was “about” slavery. The Brooks-Sumner affair is widely portrayed as a key event that led to the “Civil War.” A recent book by Stephen Puleo was even published in this light called “The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War.”

The truth is that the Brooks-Sumner caning was not a cause of the “Civil War.” It was a matter of personal honor, which people took more seriously at that time. The whole event was capitalized on by Sumner, who constantly sought the sympathy and grief of others for his “injuries.” As historian Howard Ray White has pointed out, Sumner may have been injured but the extent was extremely exaggerated to garner support to his agitation. He may not have returned to his seat while “recovering” but was able to show up to vote for the tariff. This goes to show that some historians will go to great lengths to portray the south as a scapegoat for the “Civil War,” even going so far as to claim a scuffle between two politicians led to the deaths of 650,000+ men.