Want to learn about one of the greatest statesmen that the United States has ever produced? Then get hold of John C. Calhoun: American Portrait by Margaret Coit.

When this beautifully-written book received the Pulitzer Prize for Biography in 1951, it was generally agreed that Coit had redeemed Calhoun as a major and admirable, even heroic, figure in American history. Even “liberal” historians of that time agreed. One result was that a U.S. Senate committee chaired by John F. Kennedy selected Calhoun as one of the five greatest Senators of all time.

How the times have changed! But Coit’s book has not changed and is still a marvelous correction to presently-distorted history as well as a stellar example of the biographer’s art.

From 1811 to 1850, as Representative from South Carolina, Secretary of War, Vice-President for two terms, Secretary of State, and Senator for a total of fifteen years, Calhoun was a central figure in the political life of the Union during its great period of continental expansion.

For most of this career Calhoun was either outside the two-party system or at odds with the leaders of the party he was identified with. He never had any significant patronage or party organisation behind him, unlike most of the major figures of his time. He was loved by many and respected by many more, and not only in the South, but he never enjoyed the mass popularity of Andrew Jackson or Henry Clay. He came from what he called “a gallant little State.”

Despite the absence of all such hallmarks of political power, Calhoun for 40 years was a force that had to be reckoned with, a major player. What he had to say always arrested attention and had a large and sometimes decisive influence on public opinion, party platforms, and legislation. He was an independent patriotic voice that rose above the shallow, opportunistic, popularity-seeking positions of leading politicians, always casting his political arguments in principled and philosophical terms. He was, as he consciously strove to be, “a statesman.” One who took a long-range view of the best interests of his society, even when it was unpopular—one who was intellectually and morally superior to “a politician.”

All though you would never hear it in discussions these days, Calhoun was not only concerned with slavery and States’ rights. He was an expert on free trade and tariff, banking and currency, taxation and expenditure, war and peace, foreign relations, Indian policy, the public lands, internal improvements, the two-party system, and the conflict between legislative and executive power. A historian of banking has written that Calhoun was the only public man of the time who really understood the subject.

But Calhoun, alone among the leaders of his time, was not only a public man but a political philosopher. In this he resembles the Founding Fathers more than his own or later generations. While in some quarters he is considered the chief villain of American history, it is true that at no time during his life and after has his thought lacked weighty admirers. The admiration is international and often from unexpected quarters.

Calhoun’s best biographer Margaret Louise Coit (1919—2003) was, interestingly, born in Massachusetts of old New England stock. But she grew up in North Carolina and was educated at the Woman’s College of North Carolina (now the University of North Carolina at Greensboro). Margaret Coit was not an academic historian, for which we should be eternally grateful. She worked as a journalist in Washington before becoming a successful writer of a number of books, including a biography of Bernard Baruch, South Carolina-born adviser to Presidents. In later years she lived in Massachusetts with her farmer-poet husband Albert Elwell.

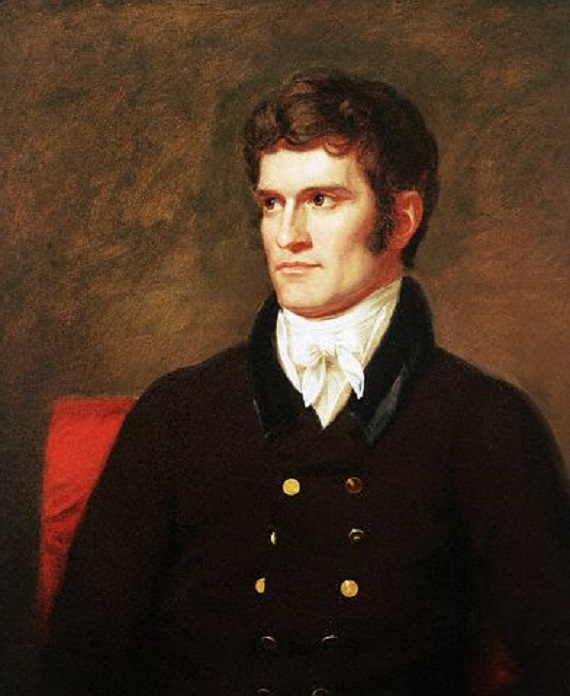

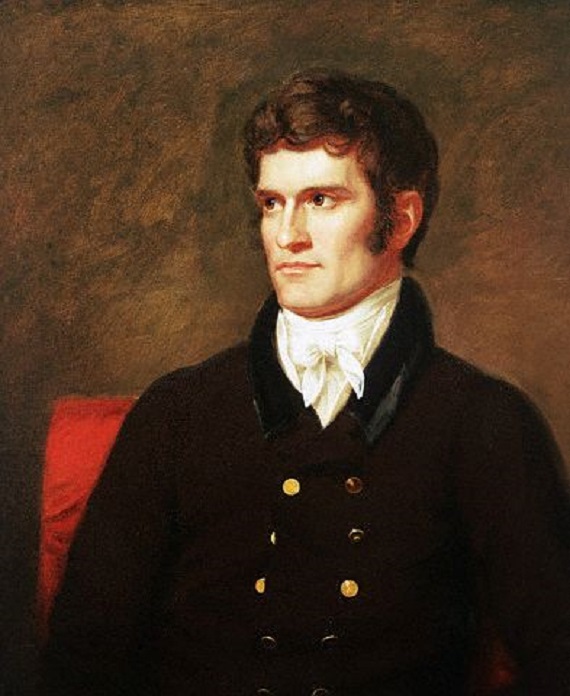

Calhoun, of course, is always represented by the Brady daguerreotype taken in the last months of his life—the wild-haired fanatic, “cast-iron man,” who has frightened generations of Yankee schoolchildren. Margaret Coit discovers for us the real Calhoun—a handsome man of charm and integrity who won the respect of army officers, frontiersmen, and hard-fisted labour leaders, and even unwilling young abolitionists.

There was a Calhoun who was most happy (like Washington and Jefferson) when engaged as a farmer; who was the too-indulgent father of many children; who in a later era might well have been a scientist. He had such a characteristically American enthusiasm for technology and material progress that in his 50s he spent nine days clambering over the most rugged part of the Appalachians to satisfy himself about the best route for a railroad. There was no “cast-iron man” but a Calhoun who could charmingly whisper verses in the ear of President Tyler’s young bride to set her at ease at her first state dinner.

And in this constructive and consoling achievement in biography, Coit most admires the tragic hero who struggled not to destroy the Union, but to warn the American people of the destruction that would come.