Introduction

The Civil War served as the deadliest conflict in U.S. history. Most scholars agree there were around fifty to one hundred major battles. Outside of these major engagements were skirmishes ranging from the coast of Maine, to the desert of New Mexico, to the Ozarks of Missouri and Arkansas. While the historical battles ultimately led to the Union winning the war, skirmishes must not be ignored.

Every engagement in the conflict was unique. The Ozarks, the region often described as southern Missouri and northern Arkansas, played a crucial role in both the Union and Confederate campaigns. First, Missouri was a divided state. The southern part of the state contained a significant number of Confederate sympathizers; further, the people in Missouri experienced much bloodshed. Records today account for over 1,000 battles making Missouri “the third-most fought-over state after Virginia and Tennesse.”

This article shares the story of Alfred Cook, his militia, and Cook’s Cave. Although Cook was not a member of either organized Army, he was a known Confederate sympathizer with a history in the south. Further, his family was said to have challenged Union demands, and he eventually found himself an enemy of the U.S. government. The writer desires those who read this article to gain an understanding of the militiamen of the Civil War and, most importantly, gain insight into the story of Cook’s Cave.

Alfred Cook

Alfred C. Cook was born on November 11, 1819, in Kentucky. He was around forty years old by the time the Civil War broke out. Cook’s parents moved to Missouri years before the conflict. Growing up in Taney County, Missouri, Cook lived in the heart of the Ozarks. The late historian Elmo Ingenthron shares:

Cook, age 40, and his wife, Rebecca Gimlin Cook, and their seven children, were living on a farm a mile or more north of Taney City in Taney County, MO. Both Alfred and Rebecca were descendants of slave-holding families. Their parents, with their family slaves, had come to Taney County in the 1830s and settled on good farmland in the Swan and Beaver Creek valleys.[1]

Cook never joined the Confederate Army, nor did he initially seek involvement in any militia. No accounts exist to explain his reluctance to join the official Army. However, in Missouri, his family was harassed by Union loyalists, ultimately leading to his departure from the state to Marion County, Arkansas.[2] He relocated to avoid conflict, yet it provided further pain and suffering, including starvation for his family. Ingenthron emphasizes the danger Cook faced:

During the last two years of the war on the border, it was dangerous for any man to dwell at home with his family. If he was known to be at home, he might be called to the door and shot by some fanatic. Many men lost their lives in this manner. The Confederate sympathizers, and men whose loyalties were unknown, were plagued by the Mountain Feds scattered through the area, who served as informants for the Unionists.[3]

While no official records mark Cook and his family as supporters of the Confederates, the consensus is the family were proud southerners, which led to regular harassment from Union loyalists and troops. Missouri had one of the strongest bands of Home Guard troops that regularly roamed the region, eventually hunting for the infamous Jesse James. Although he was no rebel Jesse James, after a couple of years of harassment, Cook felt he had little choice but to respond to Union raids and persecution. Soon the isolationist formed his own militia to fight back, ultimately gaining Union Headquarters’ attention.

The Militia

Cook and like-minded neighbors were constant targets of “Union Raiders.” By the later years of the Civil War, it was widely known the Union Army regularly raided farms and homes and even burned down houses of opposing forces and their supporters. Sadly, this happened to normal, everyday citizens, including women and the elderly. The Cook family was one of these families constantly harassed. First, they encountered conflict in Missouri and fled to Arkansas. Though they anticipated peace in northern Arkansas, they never received it. Cook had enough. Alfred Cook and fellow neighbors decided it was time to fight back.

Ingenthron shares, “Cook and 13 or more others in similar circumstances banded together for their mutual protection. Cook was their chosen leader.”[4] According to family accounts, these men and their families were starving. Raids consisted of Union soldiers and loyalists robbing them of their food and supplies. Having seven children, Cook determined it was necessary to defend himself and his family. The newly formed militia acted first by “stealing back what was theirs.” Their first attack focused on Missouri soldiers who crossed the border and raided their homes.[5] They considered such campaigns as “retaliatory raids,” specifically targeting those men who plundered them. Surprisingly, Cook’s militia was successful, and the men’s families were no longer suffering. Ingenthron comments on their success, “The raiders’ vindictive and deadly activities soon came to the attention of the Federals, who branded Cook’s band ‘bushwhackers,’ subject to be hanged if captured or shot on sight.”[6] The men constantly outsmarted their captors, hiding in an abandoned house and eventually an Ozark cave. While Cook and his military initially fought back only against those who raided them, some accounts explain his militia soon accosted any Union or loyalist force crossing into their region. Needless to say, his band had gained the attention of Missouri Headquarters, and they placed an official order to get rid of the rebels. Once the Union burned down the abandoned house, the Feds searched for months looking for this troublesome militia, finally gaining word of their whereabouts.

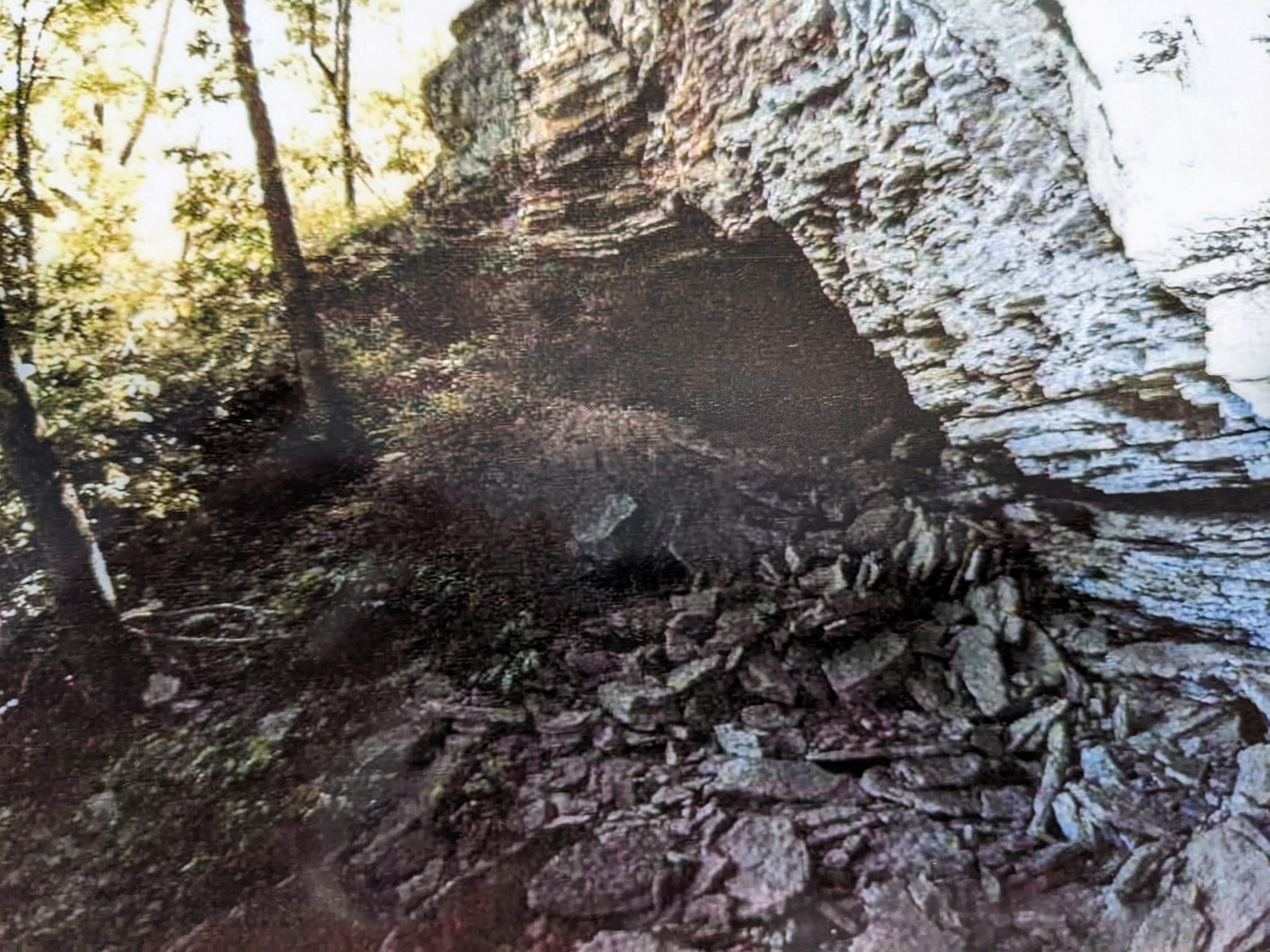

Cook’s Cave

The rumor was Cook’s militia was hiding out in a nearby cave. Though a strategic point of escape and rendezvous, the cave had one major drawback, there was no rear exit point. Knowing the location of Cook’s family’s residence, Captain William L. Fenex and Lt. Willis Kissel found one of Cook’s young sons and ordered him to take his unit to his father’s hideout. The son complied and led the soldiers to the infamous Cook’s Cave. The reader can only speculate on the measures used to force the young boy to comply. Ingenthron shares the story:

With his troops surrounding the cave entrance, Kissel demanded that the raiders surrender, a demand which, if complied with, could mean death. When no one emerged, Kissel called out that the raiders would be treated as prisoners of war and not harmed if they surrendered. He gave the embattled men four hours to decide. At the expiration of the time allotted, 11 of the men emerged from the cave. Cook and two others refused to surrender.[7]

Kissel then ordered a “huge fire to be built on the edge of the cave.” The wind blew, bringing the smoke into the cave and forcing Cook and his men out of the hideout.[8] Once out of the cave, shots rang. Union soldiers killed all three men, including Alfred Cook.[9] The official report from Captain Fenex shared:

I would respectfully report to you that on the 8th instant, I started a scout of twenty-five men, under the command of Lt. Kissel, to look after old Snavels, whereabouts, and if possible, to capture or exterminate Alfred Cook and his band, that had so long been a terror to the loyal people of Taney, Christian, and Stone counties. After reaching the Sugar Loaf Mountains, about thirty miles south of Forsyth, Lt. Kissel there learned, through strategy, that Cook, with his band, was in a cave some two miles south of his house, when he immediately determined to press Cook’s son, a small boy, to pilot him to the cave, which he did and found Cook and thirteen others with him. After surrounding the cave he demanded an unconditional surrender of all in the cave, which was refused. He then gave them four hours to consult, with the promise that that surrendered in that time should be carried to Springfield and there turned over to the proper authorities to be dealt with according to the law.[10]

After the four hours had passed, the report continues:

At the expiration of the time allowed, nine of the party surrendered, leaving in the cave some five others with Alfred Cook, their leader, which explains the reason that Cook and Ed Brown were not brought to Springfield. The lieutenant and his brave boys continued to siege until the next morning when Cook and his party succeeded in getting their Southern rights. All praise to the lieutenant and his brave boys.[11]

Brigadier General J.B. Sanborn summarized the results in a similar report:

General Orders 231, from headquarters Department of Missouri:

Captain Fenex this day brought in eleven prisoners of Alfred Cook’s band. He reports having caught Alfred Cook and fifteen of his men in a cave east of Sugar Loaf Prairie. Eleven of these surrendered, but Cook, Brown and two others refused to surrender and were killed. [12]

Though discrepancies exist between Ingenthron’s and both official reports (total number of militia members, including those killed), all three accounts have Alfred Cook, and Ed Brown listed as two of the deceased militia members.

Brigadier General J.B. Sanborn

One of Cook’s children, John E. Cook (age 16 when his father died) reported his father was “shot down at the mouth of the cave.”[14] Ed Brown ran out of the cave and, after being hunted down, was shot dead some “one-quarter miles away from the cave.”[15]

Cook’s son shared:

An ox wagon pulled by a yoke of cattle was brought into the hollow below of the cave and the dead men were carried down the mountainside to the wagon and placed in the wagon-box and hauled four miles and stopped one-half mile of the old Abe Kneeling place where a grave was dug and a plain coffin prepared for the reception body of his father.[16]

Grave of Alfred Cook and the men who refused to surrender

The reader can only speculate why Cook and the other men did not surrender. The word was out that Cook’s capture and hanging was an order from headquarters. Perhaps Cook feared execution if he in fact, complied. After all, he was the leader of the organized militia. Nevertheless, their reasons for refusing to surrender will never be known for certain.

Today, near Sugar Loaf Prairie, Arkansas, Cook’s Cave still remains. Locals well know the cave. It has a long history of being used as a hideout and is the past home of many animals, from wolves to bears. The late Ozark legend Silas Claiborne Turnbo recalled visiting the cave some years after the Civil War incident. Upon entering the cave with his guide, John Campbell, they encountered several black bears: “Mr. Campbell shot and killed one bear, scaring off the others.”[17] The reader must realize Cook and his band were just one militia. The Ozarks contained an estimated two to three hundred militiamen in the vicinity of Cook’s cave. The Union could not successfully rid the area of all “rebels.” Ingenthron pondered the aftermath of Cook’s death: “We have no specific record of the hardships and heartaches that Rebecca and her children must have endured in the ensuing months.”[18]

Conclusion

While not as exciting as studies of major battles, skirmishes have a place in Civil War history. The story of Cook and his band is more than a story about a group of militiamen. The reality is everyone was affected by the War Between the States. Whether or not one desired to remain neutral, neutrality was almost non-existent. It was apparent that Cook and his family were southerners at heart. When tension arose in Taney County, Missouri, they left their home, seeking peace and safety away from the Union. Unfortunately, they never found peace.

Cook and others like him faced harassment, violence, and raids that starved their families in the foothills of Arkansas. By all accounts, these men and families joined as one to defend their homes and feed their families. Today, we can have empathy for their situation. Once they chose violence, they were the enemy of the Federal troops stationed in Missouri. Alfred Cook and a few of his men met their end in January 1865, though his family carried on. Rebecca and the children headed to Missouri following the war. The author of this article is one of Cook’s descendants, the great (x3) grandson of Alfred Cook. My great grandfather (x2) was Wilson C. Cook, the youngest boy of Alfred, only four years old, around the time his father perished. Poverty and hardship did in fact follow the Cooks well into my grandmother’s life and childhood. Nevertheless, Cook’s legacy continues in his descendants.

Cook made the unmistakable decision to fight back. Albeit surrendering was an option, he most likely chose not to out of fear of immediate death. Regardless, in studying the lives of these “rebels” or militiamen, we often learn they were ordinary people who usually sought peace. Yet, like any person alive today, they desired to provide for their families and often made the difficult decision to fight back rather than be plundered and bullied by an invading army. Let us never forget the men who served their families during the Civil War.

*********

[1] Elmo Ingenthron, Borderland Rebellion (Branson: Ozarks Mountaineer, 1980), 292.

[2] Ibid., 293.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Elmo Ingenthron, Borderland Rebellion, 293.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Elmo Ingenthron, Borderland Rebellion, 295.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Military Records, “Records of Capt. William L. Fenex,” (letter, January 17, 1865), Fold3.com.

[11] Military Records, “Records of Capt. William L. Fenex,” (letter, January 18, 1865), Fold3.com.

[12] Ibid.

[14] S.C. Turnbo, The Alph Cook Story, The Turnbo Manuscripts, https://thelibrary.org/lochist/turnbo/V1/ST002.html/

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] S.C. Turnbo, A Spring of Blood, The Turnbo Manuscripts, https://thelibrary.org/lochist/turnbo/V27/ST769.html.

[18] Elmo Ingenthron, Borderland Rebellion, 295.

Yes sir.

Alfred Cook was my great grandfather too. My linage is through John Cook. He settled in Oklahoma after the war.