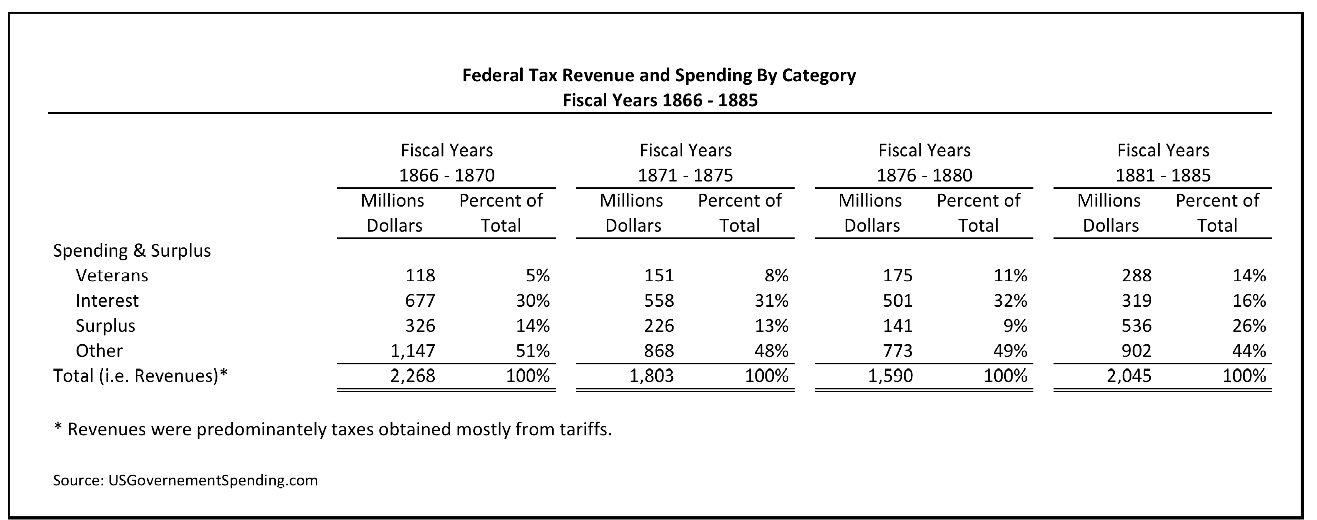

The table below summarizes Federal Tax revenues and spending for twenty years following the Civil War. For clarity, the total period is separated into four discrete five-year intervals. As may be observed, more than half of Federal tax revenues were applied to three items: (1) Federal debt interest, (2) budget surpluses, and (3) veterans benefits. Although compelled to pay their share of taxes to fund them, Southerners derived no benefit from the allocations. They essentially represented a form of reparations for being on the losing side. Nor were they the only form.

First, virtually the entire Federal debt was owed to Northerners who were the chief bondholders. Nearly all bonds were sold during the Civil War as the debt increased more than forty-fold from $65 million to nearly $2.7 billion. In contrast, debts of the Confederate states were repudiated. Finally, Federal debt interest had to be paid in specie, as opposed to greenbacks, which traded at a discount to specie.

Second, the budget surpluses were caused by protective tariffs that generated more income than needed to operate the Federal government. Dutiable items were taxed at over 40%. The purpose of the excess was to restrict competition for domestic producers. It was a form of corporate welfare that largely remained in place until Woodrow Wilson became president in 1914. It was harmful to farmers – both white and black – who sold primarily to export markets, which were competitive to the Nth degree. Theoretically, it could encourage trading partners to retaliate by imposing tariffs on USA products entering foreign markets thereby harming US exporters.

The budget surpluses were also used to pay down the Federal debt, which again was of no benefit to Southerners. Surpluses were also set-aside to redeem greenbacks at face value for specie even though greenbacks could have been purchased for as little as forty-cents on the dollar in the summer of 1864. Few Southerners had greenbacks at the end of the war because it was a Yankee currency.

Third, former Confederates derived no benefit from Federal spending on Union veteran pensions. Ex-Rebel soldiers could only collect pensions from their respective states. Few states had much money for such expenses for years after Appomattox and the Federal government obviously made no contributions.

Aside from the items specified above, what about the rest of the budget? Did not some of it go to the Freedman’s Bureau and other areas that benefitted the South? Well, yes, some..but it was a vanishingly small amount.

While the Freedman’s Bureau did good work with what it had, most of the Federal spending not included in the three highlighted items above were devoted to military defense and the post office. For example, in Fiscal 1870 over 83% of tax revenues were for (a) interest on debt, (b) surplus, (c) defense, (d) veterans benefits, and (e) the post office.

There was very little public works spending in the South. Despite the budget surpluses, outside the Freedman’s Bureau – which was primarily for African-Americans – there was almost no Federal economic aid to the South. From 1865 – 1873 the Federal government spent $103 million on public works, but less than 10% went to the former Confederate states. New York and Massachusetts alone got more than twice the amount of the entire South.

Instead the Federal government taxed cotton. In just a few years the tax raised $68 million, which was more than seven times the amount of public works spending in the region during that 1865 to 1873 period. Although the constitution required that taxes be uniform, there were no taxes on commodities from farm states outside the South. The tax was repealed partly because an African-American Alabama congressman explained that is was harmful to blacks as well as whites.

An objective look at Reconstruction seems to echo Pogo’s conclusion about nuclear energy: “It’s not so new and it not so clear.”