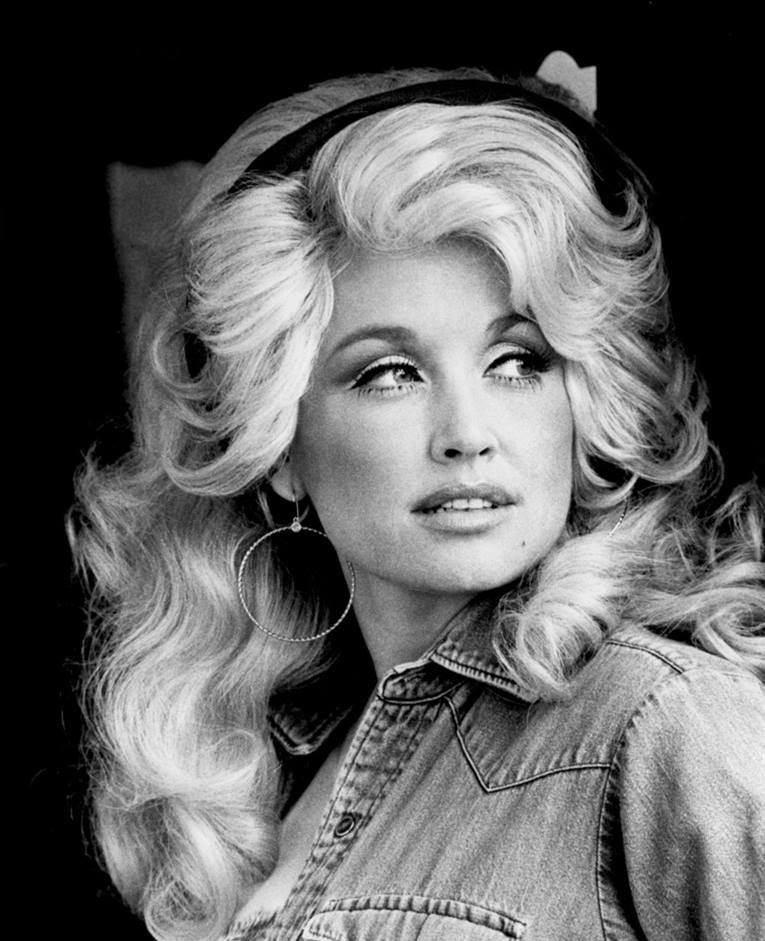

Greatness. In Southern music, “greatness” is rarely the result of innovation alone. More often, it emerges from endurance—specifically, the capacity to move through cultural, commercial, and institutional pressure without surrendering. The South has produced countless musicians whose work crossed boundaries of region, genre, race, and class, but far fewer who managed to do so while retaining control over their voice, their narrative, and their sense of place. The road through Southern music is littered with forgotten examples of rare, unique musicians with a captivating sound who were discovered, changed, altered, and transformed into something no longer rare, unique, and captivating. The very industry that gave them fame surgically removed the outlying qualities that fueled the fame. Only a very rare and very few Southern artists managed to sustain control over their sound across the decades and remain true to the sound that brought them to our attention in the first place. It is within this narrow and demanding category that Dolly Parton belongs.

Many musicians are doing well to simply survive the friction between Southern identity and national culture. Dolly Parton outperforms it. She leaves it in the dust. Her career is not a story of compromise softened by charm, nor of assimilation disguised as versatility. Instead, it represents a sustained exercise in Southern intelligence—linguistic, musical, social, and strategic—applied with consistency over time. She does not function as a pressure case within Southern music history, requiring explanation for how she “escaped” regional limitations. Rather, she stands as a capstone figure who demonstrates what Southern identity looks like when it remains intact across crossover, celebrity, and generational change. There’s no one like Dolly, there never will be anyone like Dolly, and there was never supposed to be another Dolly.

Dolly Rebecca Parton was born January 19, 1946 in Sevier County, Tennessee, within the Appalachian region of East Tennessee, an area whose cultural and musical traditions differ significantly from both the Deep South plantation belt and the commercialized Nashville industry that would later frame her career. This distinction matters. Appalachian culture carries its own linguistic rhythms, musical forms, and storytelling conventions, shaped by relative geographic isolation, economic hardship, and a long oral tradition in which verbal precision and narrative clarity carried real social weight. Parton’s early life unfolded within material poverty, but it was also marked by an extraordinary density of cultural inheritance: mountain ballads, church hymns, family harmony singing, and a community structure in which music was participatory. Nobody cared about stages. They cared about front porches.

From the beginning, Parton’s songwriting reveals an understanding of her home as a foundation of her identity without being simple nostalgia. Songs such as “Coat of Many Colors” do not romanticize poverty or aestheticize hardship. Instead, they articulate dignity through narrative control. The song’s power lies in its refusal to bend to ridicule. The child narrator understands precisely what the coat represents, how others perceive it, and why those perceptions are ultimately irrelevant. The song is actually a perfect metaphor for the whole Southern experience in that the things non-Southerners mock about the South are the very things of which we are most proud. This insistence on self-definition—on telling one’s own story without apology or embellishment—will remain central to Parton’s work across genres and decades.

Unlike many artists who later rediscover their roots as branding tools, Parton never treats Appalachian identity as a costume. It is not something she puts on or takes off depending on the audience. It is the baseline from which she operates. Even as she enters spaces historically hostile or dismissive toward rural Southern women, she does so without ever translating herself into a more “acceptable” cultural language. Her work suggests that place, when genuinely inhabited, does not need to be defended. It simply persists. No explanation, and certainly no apology, should ever be given when one is not necessary.

In Southern music, the accent is never just something phonetic. It’s not just the way Dolly talks and she can’t help herself. The Southern accent functions as a cultural boundary marker of authenticity and legitimacy. At the same time, it becomes one of the first targets of institutional pressure once an artist approaches crossover success. To retain a strong Southern accent is often framed as risky; to soften it, as strategic. Dolly Parton’s significance lies in her refusal to accept this binary.

Parton’s speaking voice retains a bright, unmistakable East Tennessee drawl—nasal, quick, rhythmically playful, and immediately recognizable. Rather than neutralizing this sound in public life, she foregrounds it, allowing it to function as both identification and disarmament. In singing, however, she demonstrates remarkable technical control over how that accent operates. Early recordings such as “Jolene,” “My Tennessee Mountain Home,” and “The Seeker” lean fully into Appalachian vowel shaping, elongated diphthongs, and melodic contours that mirror mountain speech patterns. In these songs, her accent is not a gimmick she uses to decorate the melody; it generates it.

By contrast, crossover recordings such as “Here You Come Again” reveal a calculated modulation of vocal delivery. Her Southern accent remains present but scaled back and less dominant, functioning as coloration rather than structural driver. This is not an example of Dolly “selling out” and erasing her culture. It is selective emphasis. Parton does not lose her accent in pursuit of broader audiences; she deploys it differently, and the distinction is crucial. Where many artists experience crossover as a one-way dilution of regional markers, Parton treats crossover as reversible, which is such a smart move. She moves between vocal registers without destabilizing and her Southern identity remains unquestioned.

This control over accent represents a form of cultural literacy often underestimated in discussions of popular music. Parton understands that accent can function simultaneously as an authenticity marker, an emotional amplifier, and a commercial signal. Her greatness lies in managing all three without allowing any single one to dictate the terms of her work.

Dolly Parton’s songwriting output is extraordinary not merely in scale but in narrative precision. She writes with an intuitive command of Southern storytelling conventions: linear progression, moral clarity without preachiness, emotional specificity grounded in lived detail, and restraint that amplifies rather than diminishes impact. Her songs are not abstract metaphors. Instead, they operate through concrete scenes, named emotions, and clearly articulated stakes. “Coat of Many Colors” is not a symbolic coat that projects moral lessons, but an actual, physical coat from her childhood that delivers an emotional gut punch.

“Jolene” remains among the most instructive examples. Structurally minimal and harmonically spare, the song depends almost entirely on narrative tension and vocal delivery. It follows a repetitive verse-refrain form that is significant because the song has no bridge. There is no harmonic escape, no emotional release, and no new narrative perspective. The song is powerful because it is minimal. The repeated invocation of the name itself becomes a structural device, stretched through Appalachian vowel shaping into a sustained emotional plea. The narrator does not rage, accuse, or posture. She speaks from vulnerability without relinquishing dignity and avoids melodrama. The power of the song comes from its containment.

This rhetorical restraint reflects a deeply Southern mode of expression, particularly among women, in which emotional honesty is paired with self-control. Because society expects women to get hysterical, it is significant that she goes out of her way to remain calm when she has every justifiable reason to go nuts. The narrator’s authority derives not from dominance but from clarity. She knows what she fears, what she values, and what she is asking. The Southern accent reinforces this authority rather than undermining it, embedding the plea within a recognizable cultural grammar.

Elsewhere, Dolly Parton extends this narrative authority across thematic and generic boundaries. “9 to 5” translates working-class frustration into a national labor anthem through humor that functions as critique rather than deflection. The song’s rhythmic insistence mirrors the monotony it describes, while its wit invites solidarity without flattening experience. Humor, for Parton, is not avoidance; it is precision.

Few aspects of Dolly Parton’s career have been more persistently misunderstood than her public persona. Her exaggerated femininity, self-deprecating humor, and deliberate embrace of visual excess are often misread as capitulation to stereotype or distraction from seriousness. In reality, they represent one of the most sophisticated examples of strategic persona construction in modern American music.

It would be disingenuous to discuss this visual strategy without acknowledging the most conspicuous feature of Parton’s appearance, which has been remarked upon so obsessively that it has almost ceased to be seen clearly at all. Her exaggerated bust, far from being an accidental byproduct of glamour, functions as part of the same deliberate overstatement that governs her hair, wardrobe, and stage presence. It is excess worn knowingly. Dolly Parton purposefully makes herself visually impossible to ignore. She removes the element of voyeuristic discovery and replaces it with self-authored spectacle. By exaggerating femininity to the point of caricature, she renders it non-threatening, even disarming, while simultaneously retaining control over its meaning. The joke, crucially, is never on her. She names it first, laughs first, and in doing so renders commentary toothless. What might have been used to trivialize her instead becomes another layer of armor—one more way she controls the terms under which she is seen, discussed, and ultimately underestimated in male-dominated industries and hostile media environments.

Crucially, the persona never substitutes for nor replaces the work. Parton’s songwriting credits, publishing control, and business decisions remain central to her career. From retaining ownership of her catalog to building Dollywood as a regional economic engine rather than a vanity project, her actions demonstrate long-term strategic intelligence. The persona draws attention; the Southern identity determines outcomes.

This distinction separates Parton from many crossover figures whose visibility outpaces their control. She does not trade seriousness for accessibility. Instead, she uses accessibility to protect seriousness, ensuring that her work remains legible on her own terms.

Crossover success often functions as a loyalty test within Southern music culture. Artists who cross too far are accused of abandonment; those who refuse are marginalized. Dolly Parton reframes this equation by refusing to relocate her center of gravity. She crosses genres, media, and audiences without displacing her foundational Southern identity. In this ingenious strategy, she’s not the one doing the crossover – we are.

Her pop recordings do not replace her country work; they coexist alongside it. Her film roles do not eclipse her songwriting; they extend its reach. Even her philanthropic efforts reflect a Southern ethic of community investment rather than celebrity branding.

The Imagination Library, which provides free books to children regardless of income, is structured not as a publicity vehicle but as a quiet, scalable infrastructure rooted in early literacy and local partnership. Her long-term investment in Dollywood similarly emphasizes regional employment, vocational training, and economic stability in East Tennessee rather than spectacle for its own sake. Even her disaster relief efforts—most notably her direct financial support to families affected by the 2016 Great Smoky Mountains wildfires—prioritize immediate, practical aid over symbolic gestures. In each case, the emphasis remains consistent: help that stays put, serves neighbors first, and resists the logic of performative charity.

Dolly is always able to occupy multiple spaces simultaneously, because her authority remains consistent across them. This consistency is not accidental. It is the result of sustained control—over voice, narrative, and public meaning. Parton does not drift into crossover; she navigates it.

Longevity is something elusive and rarely neutral. Careers endure either because they adapt indiscriminately to shifting trends or because they remain anchored while selectively evolving. Parton exemplifies the latter. Her relevance across decades does not stem from constant reinvention but from cumulative intelligence. Each era builds upon the last rather than erasing it. It’s never a “new” Dolly, but just the same Dolly, but comfortably adapted for newer times.

This endurance also reframes gendered expectations within popular music. Parton is neither frozen in youthful novelty nor relegated to legacy status. She remains culturally present because she never ceded interpretive authority over her work or her voice. Her career suggests that endurance, when grounded in Southern identity, is not stagnation but stability.

Dolly Parton is often described as singular, as though her success exists outside the logic of Southern music history. She is thought of as an exception whose success can probably never be replicated. This framing misses the deeper truth. She is not an anomaly within Southern music. She is not an exception to Southern musical tradition. Dolly Parton is its most fully realized expression when talent, instinct, intelligence, and Southern culture align.

Her greatness has nothing to do with songs written or records sold, but in the demonstration that Southern identity can move through modernity without apology or erasure. She proves that accent can function as asset rather than liability, that persona can operate as strategy rather than compromise, and that crossover doesn’t have to entail displacement.

Dolly Parton is a master practitioner of Southern endurance done right and a little ol’ Southern girl who was raised right.

I have always loved all of her songs, I particularly appreciate the quality of her voice because it reminds me of my godfather’s wife’s (aunt Bertha’s) voice.

But I did take issue with her decision a few years back to permanently ban the singing of Dixie on her program. For me, she caved to the nascent Woke agenda.

Dolly’s woke. Anyone who reads the Bible knows the coat of many colors created conflict among brothers. Favoritism is not usually something wise parents exhibit.

While I do agree that Dolly Parton is a great and talented singer and songwriter, she lost all of my respect when she discarded the name “Dixie” from her Dixie Stampede in Branson, Missouri, thereby denouncing her Southern heritage. She further lost credibility when she endorsed, and financed, the deadly COVID shot. She has gone pure “woke” and I would not walk across the street to see her perform, and certainly will not spend one dime on any of her products or businesses.