This essay was presented at the 2019 Abbeville Institute Summer School on the New South.

In 1965 Texas novelist William Humphrey wrote:

If the Civil War is more alive to the Southerner than the Northerner it is because all of the past is, and this is so because the Southerner has a sense of having been present there himself in the person of one or more of his ancestors. The war filled merely a chapter in his . . . [family history] . . . transmitted orally from father to son the proverbs, prophecies, legends, laws, traditions-of-origin and tales-of-wanderings of his own tribe. . . It is this feeling of identity with the dead (who are past) which characterizes and explains the Southerner.

It is with kin, not causes, that the Southerner is linked. Confederate Great-grandfather . . . is not remembered for his (probably undistinguished) part in the Battle of Bull Run; rather Bull Run is remembered because Great-grandfather was there. For the Southerner the Civil War is in the family.

Clannishness was, and is, the key to his temperament, and he went off to war to protect not Alabama but only those thirty or forty acres of its sandy hillside, or stiff red clay, which he broke his back tilling, and which was as big a country as his mind could hold.

Undoubtedly Humphrey was revealing feelings carried forward from his Texas childhood during the 1930s. Back then a few veterans were still alive to pass along their memories to youngsters like Bill. He later used those recollections to portray an incident in his best-known novel, Home from the Hill, which Vincente Minelli made into a movie.

About twenty years after the war a foppish stranger stepped off the Dallas-bound train when it stopped at Clarksville. Even though he spoke English none of the whittlers at the station could understand him, which they later learned was due to his Italian accent. But eventually the stranger—who identified himself as a professor—was granted an audience with the aldermen during which he explained that he could build a marble monument to the Confederate infantryman for $5,000. For $25,000 he could erect one depicting a mounted cavalryman, or an officer.

The town chose the $5,000 option. After the professor labored creatively and submitted a finished design the aldermen gave him a $2,500 deposit. A year later he returned with the sculpted components and erected the statue. The unveiling was a celebration that attracted nearly everyone in town, white and black.

A good many years elapsed before anyone from Clarksville traveled far along the railroad from whence the sculptor arrived. But when one resident eventually traveled to Georgia he noticed that there was “hardly a town of monument-aspiration size along the railway line all the way to Atlanta without a copy of our soldier.”

Statue critics say the Confederate soldier fought for slavery. But fewer than 30% of Southern families owned slaves. In truth, according to historian William C. Davis, “The widespread Northern myth that Confederates went to the battlefield to perpetuate slavery is just that, a myth. Their letters and diaries, in the tens of thousands, reveal again and again that they fought because their Southern homeland was invaded. . .”

Moreover, when their impoverished families were finally able to collect enough money to erect memorials, they honored the soldier for his battlefield sacrifices. It’s obvious in the words contained in monument inscriptions. A typical example is on the Silent Sam statue torn down two years ago by a mob of Chapel Hill students at the University of North Carolina. It reads:

To the sons of the university who entered the War of 1861–65 in answer to the call of their country and whose lives taught the lesson of their great commander [Robert E. Lee] that duty is the sublimest word in the English language.

Honorable sentiments erased by political correctness.

When the inscriptions did address Southern causes, they tended to focus on constitutional rights such as limited government and state sovereignty. One example from a statue removed in St. Louis reads:

To the Memory of the Soldiers and Sailors of the Southern Confederacy.

Who fought to uphold the right declared by the pen of Jefferson and achieved by the sword of Washington. With sublime self-sacrifice they battled to preserve the independence of the states which was won from Great Britain, and to perpetuate the constitutional government which was established by the fathers.

Actuated by the purest patriotism they performed deeds of prowess such as thrilled the heart of mankind with admiration.

Valid points surrendered to the big-government dogma of our age.

Knoxville unveiled her first Confederate statue in 1892, well ahead of most other Southern towns. Since that was only twenty-seven years after the War had ended, the dedication speaker was undoubtedly acquainted with many veterans when he said, “the Southern soldier believed his allegiance was due, first to his state and then to the general government. . . So when his state called for his service, he responded believing it to be his duty.” Without foreknowledge of the Spanish-American war still six years in the future he added presciently, “I am persuaded that the soldier from Mississippi or Louisiana would give his life in defense of his country today as readily as one from Massachusetts or Maine.” Finally, he quotes a mother’s elegy that serves as a soldier’s epitaph:

What need of question now, whether he was wrong or right?

He wields no warlike weapons now, returns no foeman’s thrust

Who but a coward would revile an honest soldier’s dust?

Brave words that too many of today’s academic historians defy behind tenured sinecures, to their everlasting shame. Some day they may find themselves as regretful as Jane Fonda over her Hanoi visit during the Vietnam War.

Few today comprehend the magnitude of the Confederate warrior’s sacrifice. About 300,000 Confederate soldiers died when the region’s population was only nine million. If the United States were to suffer proportional casualties in a war today our losses would total 11 million, which would be twenty-six times greater than our dead of World War II.

Given such oblations, the Confederate soldier’s surviving family members wanted to memorialize him. Memorial Day evolved after Federal occupation troops observed Southern women spreading flowers upon the graves of their husbands, sons and brothers during the war. A year after the war the ladies of Columbus, Mississippi strewed flowers on the graves of both the Confederate and Union dead in the town’s Friendship Cemetery. Their gesture started a movement that spread and in the North May 30th was selected as National Memorial Day in 1868.

Since the war had impoverished the South, the Southern ladies could do little more than lay down flowers. There was no money for statues and Union veterans initially opposed permanent Confederate memorials. But when the sons of Confederate veterans eagerly joined the U.S. Army to help win the Spanish-American War, the aging Union Civil War soldiers concluded that their former rivals were also Americans, who deserved memorial recognition.

Thus, the twenty years from 1898 to 1918 witnessed the installation of 80% of the signature courthouse square Confederate statues still standing in many Southern towns. During that period the typical surviving Confederate soldier aged from 58 years to 78 years. Memorial placements—North and South—surged between 1911 and 1915 because it was the War’s semi-centennial and the old soldiers were fading away.

Today a vocal minority holds Confederate soldiers in contempt, much like the many Americans who sneered at returning Vietnam veterans in the 1960s and 70s. Mixed in with chants of “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many babies did you kill today?” some civilians mocked the soldiers. Today most Americans old enough to remember cringe with shame when recalling such incidents.

As reported in The New York Times, for example, in 1968 a one-armed vet was accosted at a Colorado college.

Pointing to the missing limb another student asked, “Did you get that in Vietnam?

The veteran said, “Yes.”

“Serves you right,” said the student.

It took years, but eventually the public abandoned the ridiculers and gave Vietnam vets their due credit thereby underscoring the maxim: “Whoever marries the spirit of this age will find himself a widower in the next.”

Thus, we should be aware that decisions to tear down century-old monuments put us at risk for future remorse. Dishonoring such monuments demeans later generations of American warriors who were inspired by the Confederate soldier.

Consider, for example, that post-Civil-War Southerners consistently came to our nation’s defense more readily than did other Americans. Even presently, 44% of American military personnel are from the South notwithstanding that it represents just 36% of the nation’s population.

Tennessee’s Alvin York was America’s most famous infantryman in World War I. Although his grandfather was a Union deserter, two of his grand-uncles sided with the Confederacy. Texan Audie Murphy was the most decorated soldier of World War II. In Vietnam, Arkansas sniper Carlos Hathcock killed more enemy than anyone and even put a bullet in the eye of an opposing sniper through the foe’s telescopic sight. (Steven Spielberg theatrically copied this in his Saving Private Ryan movie.) Each man was born into the grinding poverty that typified much of the South for a century after the Civil War. As boys they hunted game for food, not sport.

During World War II, the first American flag to fly over the captured Japanese fortress at Okinawa was a Confederate Battle Flag. It was put there by a group of marines to honor their company commander—that happened to be a South Carolinian who suffered a paralyzing wound in the victorious assault. Some of the tank crews that freed prisoners from German concentration camps also flew the Confederate Battle Flag.

The academic community is at the forefront of those wanting to remove Confederate statues, which they characterize as racist. In doing so they violate the American Historical Society’s warning against “presentism,” which is defined as an uncritical tendency to interpret the past in terms of modern values. It fails to recognize that racial attitudes throughout America 150 years ago were different than they are today. That is why Abraham Lincoln said during an 1858 debate, “. . . I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races. . .”

Finally, toppling Confederate statues has evolved into a mob sport, with impunity for the vandals. Since such conduct requires no more bravery than kicking a puppy, we may wonder what comes next. Arcata, California has already removed a statue of President McKinley. Notre Dame University has covered a mural that celebrates Christopher Columbus’s discovery voyages. Anti-statue activists are behaving much like the leaders of the former Soviet Union where censorship and rewritten history was part of the state’s effort to ensure that the correct political spin was put on their history. In response, George Orwell warned, “The most effective way to destroy a people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.”

One argument used by those wanting to remove Confederate statues is that contemporary blacks had little chance to oppose them when they were erected. Aside from anecdotal evidence that blacks joined white crowds to observe the dedication ceremonies, one example in Mississippi provides undeniable evidence of explicit high-level black support. In 1890 the Mississippi legislature voted on a bill to appropriate $10,000 for a Confederate monument. The vote in the lower chamber was 57-to-41 in favor. All six black representatives voted “yea.” One, John F. Harris, made a supporting speech prior to the vote:

Mr. Speaker! I have risen here in my place to offer a few words on the bill….I was sorry to hear the speech of the young gentleman from Marshall County. I am sorry that any son of a soldier should go on record as opposed to the erection of a monument in honor of the brave dead.

And, sir, I am convinced that had he seen what I saw at Seven Pines and in the Seven Days’ fighting around Richmond, the battlefield covered with the mangled forms of those who fought . . . for their country’s honor, he would not have made that speech. . . . When the news came that the South had been invaded, those men went forth to fight for what they believed, and they made no requests for monuments . . . But they died, and their virtues should be remembered.

Sir, I went with them. I too wore the gray, the same color my master wore. We stayed four long years, and if that war had gone on till now I would have been there yet . . . I want to honor those brave men who died for their convictions.

When my mother died, I was a boy. Who, Sir, then acted the part of a mother to an orphaned slave boy, but my old missus? Were she living now, or could speak to me from those high realms where are gathered the sainted dead, she would tell me to vote for this bill. And, Sir, I shall vote for it. I want it known to all the world that my voice is given in favor of the bill to erect a monument in honor of the Confederate dead.

Harris was about thirty years old when he went off with his master to fight on the side of the Confederacy. After the War he studied law at the offices of Percy and Yerger in Greenville, Mississippi. The firm’s co-founder was William Alexander Percy, a former Confederate Colonel. In 1867 Percy successfully defended ex-slave, Holt Collier, who had been accused of murdering a federal officer.

Holt fought as a Confederate sharpshooter during the War and later was a guide for Theodore Roosevelt when the President visited Mississippi on a bear hunt in 1902. When word got out that Roosevelt declined to shoot a bear that Holt had trapped for him, a toy manufacturer started mass producing stuffed bears for infants. He named them Teddy Bears.

Percy’s son (LeRoy) fathered a second William Alexander Percy who authored Lanterns on the Levee in 1941. When future novelist and physician Walker Percy was orphaned at age fifteen in 1931, he went to live with his older cousin, the second W. A. Percy. While in Greenville, Walker became best friends with high school classmate Shelby Foote who had been fatherless since age five. During the next three years the two youths were treated like nuclear family in the W. A. Percy household. The patriarch officially adopted Walker and became a mentor to Shelby. Later, Walker won the National Book Award for The Moviegoer while Shelby became best known for his three-volume narrative history of the Civil War.

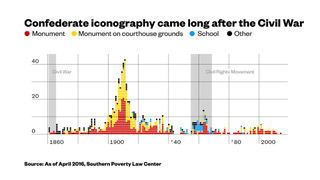

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) wants Confederate statues removed from public spaces. Several years ago, they published the chart above depicting the dates when Confederate statues were erected. As you may see, they attempt to associate the construction of Confederate statues with three eras they claim correlate to white hostility toward blacks. The attempts are as phony as a football bat.

The SPLC portrays the first twenty-year period from 1880 to 1900 as a time when Southern blacks lost voting rights and Jim Crow was enacted. Their case for this period is weak because comparatively few statues were assembled at the time. Similarly, Jim Crow and voting rights issues largely applied only to the second half of the period.

Many more statues were constructed during the second era from 1900 to 1920, which the SPLC correlates to racial lynchings and a resurgent KKK. In realty, lynchings were steadily declining during the entire period and the KKK was not resurgent until after 1920. At the start of the 1920s the KKK had only a few thousand members. Five years later, however, membership ranged between two to five million because it had become a national—not regional—organization. Indiana had more members than any state. Oregon, Kansas, Colorado, Pennsylvania, Washington, and Ohio were other strongholds outside the South. Nonetheless, by the start of the 1930s the Klan’s numbers had dwindled to insignificance.

In truth, four factors that the SPLC evades caused the building surge during the 1900 – 1920 interval. First, since the old soldiers were dying-off family members wanted to honor them while they were still around. A twenty-one-year-old who went to war in 1861 was sixty years old in 1900 and seventy-five in 1915. Second, the Civil War’s semi-centennial commemoration was a major factor motivating statue construction. Nineteen-eleven marked the fiftieth anniversary of the start of the war and 1915 was the fiftieth anniversary of its end. Third, both of the preceding points contributed to a simultaneous surge in the number of statues erected to honor Union veterans. It is only natural that Confederate descendants wanted to follow suit at the same time. Fourth, post-war impoverished Southerners generally did not have enough money to pay for memorials until the turn of the century. Notwithstanding its population growth, the region did not recover to its of pre-war economic activity level until 1900.

Few people today appreciate the efforts required to fund the century-old statues. A typical example is the 1905 monument in Chester, South Carolina. When erected blacks accounted for about 40% of the town’s 4,500 people as compared to 60% of its present 5,500 population. Fundraising began the year after the war ended in 1865 when school children were only able to raise pocket change. A second effort four years later in 1870 collected only a few dollars. In 1890 a Chester woman raised $200 with a theatrical performance. Finally, in 1900 the United Daughters of the Confederacy took charge and by the end of 1904 had about $420. Next the UDC launched a public subscription involving many small donations from Chester residents including some blacks. That increased the treasury to $2,100, which was enough to pay for the monument. In May 1905 they laid the cornerstone before a crowd that also included a minority of African-Americans.

But, to return to the SPLC’s analysis, consider the third surge of statue placements during the 1960s. The Poverty Center fallaciously attributes it to white protest against school integration and MLK’s Civil Rights Movement. In reality, the SPLC’s own graph shows that the deployment of new statues during the 1960s was a minor swell compared to the semi-centennial. Moreover, it most likely reflected the centennial commemoration as opposed to protests against black progress.

The preceding chart underscores the importance of the semi-centennial and dwindling veteran population as true motivating factors for erecting the signature public square statues. The yellow bars represent the statues placed on courthouse grounds, as opposed to cemeteries, battlefields, and private property. As may be seen, they are heavily concentrated in the semi-centennial era. There can be little doubt that they were built with some urgency caused by the shrinking numbers of vets. Only a cynic could conclude otherwise.

Unfortunately, most academic historians are cynics. Remarks by Mercer University’s Dr. Sarah Gardner reveal good examples. “It took the North’s abandonment of Reconstruction,” she argues, “before Confederate apologists could enshrine their views in public squares.” No, Dr. Gardner. In reality, since the Carpetbag regimes ended only a dozen years after the Civil War, it’s obvious that lingering Southern poverty was the chief reason that most Confederate statue-building was delayed until the twentieth century when Republican Reconstruction had been over for twenty-three years.

Even though she admits that 90% of the Rebel statues were erected after 1895 she concludes, “The purpose of these statues was not to honor the Confederate dead but to assert and celebrate white supremacy in the present.” Since the most active statue-building part of that period also coincided with the dwindling ranks of Confederate veterans, only the most extreme cynic could reach her conclusion.

Finally, she argues that the long-delayed work on the Davis, Lee, and Jackson carvings at Stone Mountain in 1963 had “nothing to do with honoring the Confederate dead of the 1860s and everything to do with asserting white supremacy . . . in the 1960s.” No, Dr. Gardner. Since 1963 was a hundred years after the war’s mid-point, it’s more likely that the Centennial Commemoration triggered a restart of the Stone Mountain carvings. Consider also, for example, that the U. S. Post Office issued five postage stamps between 1961 and 1965 to commemorate the Civil War Centennial. The chances they did that to assert “white supremacy” are about as slim as an Apache Indian getting elected Pope.

Rather than taking down Confederate monuments, we should be adding new ones that address the subjects of slavery, the Underground Railroad, black soldiers, and Reconstruction as well as the Jim Crow and Civil Rights eras. Adding new monuments for more recent heroes while keeping the old ones in place provides a tangible record of how our society evolved.

Such trends had already been in place long before Dylan Roof provided the cultural elite an excuse to tear down Confederate symbols in 2015. In 2007, for example, Arkansas erected statues on its state capitol grounds to the nine black teenagers who integrated Little Rock’s Central High School fifty years earlier in 1957. Similarly, Richmond, Virginia honored pioneering black tennis player Arthur Ashe even earlier in 1996. They built a statue of him on Monument Avenue, which is chiefly populated with Confederate heroes.

Consider also street-name memorials to Martin Luther King. Former Confederate states have far more MLK streets and avenues than similarly sized Northern states. North Carolina and New Jersey, for example, have comparable populations but the Southern state has twenty-nine MLK streets whereas the Northern one has only eight. Similarly, even though Ohio has four times the population of Mississippi, the Buckeye State has only eight MLK streets whereas the state with the Confederate banner in its flag has sixteen.

I struggled for a way to end this speech on a positive note until I read a recent blog post by Richard Williams at Relics & Bones. He quoted the wisdom of Will Durant who said, “To speak ill of others is a dishonest way of praising ourselves.” Thus, even though pictures of students triumphantly kicking a fallen statue may anger us, Durant’s quote indicates that their conduct is really a grotesque display of narcissism.

Although saving Confederate statues may be hard, we must try. Never think your corner of the world is too small to have an impact, even if that part is simply in your own family circle.