This article was originally published in the May 1916 issue of the Journal of Political Economy.

To turn men away from the “barren” field of political history is one professed object of Professor Charles A. Beard in the two volumes which he has in recent years submitted to the public. Other purposes of these interesting volumes are to call the attention of scholars to a closer consideration of men’s interests as decisive factors in history, to induce a re-examination of the actual conditions upon which the federal Constitution was posited, and to further the study of the programs of whatever democracy there was in the Jeffersonian system of government.

These purposes are certainly legitimate, and the volumes before us show both the earnestness of their author and the important results actually attained. Their general truthfulness and effect are suggested by the reactions of historical scholars. Several well-known writers have declared that the first volume was bad—very bad, and even slanderous of the Fathers of the Constitution; but when the second volume appeared some of these same men declared that Beard was not such a bad scholar after all—that his new book was a most important publication, a work which all ought to read. Some who had liked the first volume could not avoid the conclusion that the second was of doubtful value; but most people from whom the writer has had reactions agree in the view that the first installment of Mr. Beard’s study is of doubtful importance, while the second is really an excellent work.

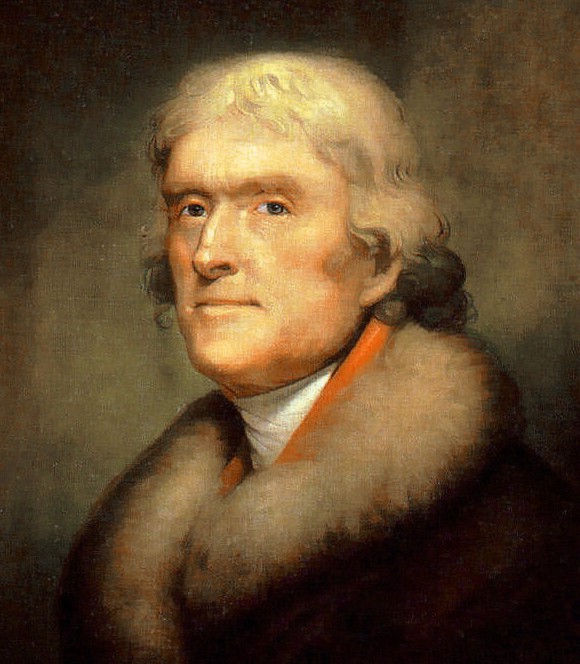

This brings to mind a fact which many readers of history are prone to forget, namely, that American historians are conservatives; they cannot allow anyone to treat the makers of the federal Constitution as other than sacrosanct; and any scholar who finds the “Fathers” just ordinary human beings, some honestly straightforward, some shrewd politicians, and still others “crooked,” as we measure men’s morals today, must expect but cold recompense for his labors. On the other hand, these same historians generally regard Thomas Jefferson as a trickster, an insincere and shallow reformer, a liar and a slaveholder. Anyone, therefore, who shows the so-called sage of Monticello to have been a rather poor sort of individual, a mere timeserver and a consistent representative of certain “interests,” as Professor Beard does, makes a “valuable contribution to our knowledge,” which is to say that the historian of today is quite a normal individual who responds to all the stimuli that moved Shakespeare’s famous Jew to say that he had feelings like other men.

To me Mr. Beard’s two volumes seem to be of about equal value, though I do not think Jefferson quite so bad a man as he is here painted. That may be set down to my pro-Jeffersonian bias. Yet these two volumes commend themselves as the most important that have come from the press in the last few years. They put the men of the period before us very much as they must have appeared to their contemporaries. This is the most that any historian can hope to do. The author’s point of view is perhaps a little too evident in certain passages. He inclines to condemn both the Federalists of 1787 and the Democrats of 1800 as representatives of “interests” seeking the good only of their respective sets, of themselves and their supporters. To him the devices and nice balances of the Constitution were invented to prevent the masses of the people from gaining control of the new federal system, as indeed they had controlled the legislatures, occasionally, of the states, notably Pennsylvania, where, according to the view of the Fathers, anarchy ruled supreme in 1787. Nor did the makers of the federal Constitution deny that their purpose was to conserve the rights of property, though they did try to temper their arguments for its adoption just enough to secure from the various conventions the necessary votes of approval.

Anyone who will read John Adams’ writings, amply quoted in Beard’s book, Marshall’s Life of Washington, McRee’s Life and Times of James Iredell, or any of the hundreds of other works which reflect Federalist opinion, will see for himself that this is true.

Mr. Beard shows distinctly and from sources hitherto unused what the more thoughtful political scientists have accepted from the time of Washington to our own day, namely, that the constitutional movement and the Federalist supremacy constituted a reaction against the radicalism of 1776, whatever that radicalism was. There is no need in our day to blink this fact. Yet many of us do blink it. We are deceived by the many statements of politicians, and especially by Chief Justice Marshall’s fiction, that the “People” made the Constitution. One of the reasons we are so readily misled is the fact that we misunderstand the so-called movements in our history. For example, most scholars, including Professor Beard, I believe, regard the states’ rights preachings of Jefferson as appeals to the states as such in order to overthrow the Federalist system. The truth is that Jefferson was all his life more of a nationalist than any of his Federalist opponents, and the resolutions of 1798-99 were but platforms upon which to mobilize the democracy of the times; they were appeals to state democracies for a union against overgrown “interests” which opposed both the legitimate rights of the states and the real interests of the people, if these meant to be self-governing.

It is this misunderstanding of the states’ rights reaction of 1798-1800 that lead’s historians to a wrong view of Jefferson and the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, and to the even more fundamental misconception of the aims of the Fathers in 1787, which were nationalist in so far as nationalism coincided with the interests of property. Another error in Mr. Beard’s second volume consists in supposing that the Jeffersonians were essentially the mouthpieces of the southern planters. No set of men in all America hated Jefferson more cordially than the planters. They “went over” to his party for the same reason that certain great manufacturers turned to Wilson in 1912: he seemed inevitable, and they desired to save themselves in time. Of course these wealthy planters came in time to dominate the new party; such men sooner or later always win control of the ruling party. One might even prophesy that this would happen in the event that the Socialists should win control of the national machinery.

Again, modern historians have been misled by the fact that Lincoln worked out his salvation of the Union by constant appeals to the Constitution, as though that document was not on the side of the property-holding interests of the South. But Lincoln knew perfectly well that the only way to win was to arouse the devotions of the plain people to an ideal constitution and thus unite men who cared for property with those who had too little wealth to understand the interests of property. But since Lincoln was a democrat, in so far as it has ever been possible for a President of the United States to be democratic, we have confused democracy and constitutionalism. The fact is that between constitutionalism and democracy there is a great gulf fixed which cannot be bridged. He who appeals to constitutions, court decisions, and static law is consciously or unconsciously an opponent of democracy; he is afraid of the people, of “the mob,” as he is likely to say.

Confusing thus the issues of our early history because of later misconceptions—because, perhaps, of the necessities of politicians like Jefferson and Lincoln—scholars have not been able to see what the Fathers were at heart desirous of accomplishing: the creation of a government of the people by an intelligent and well-to-do minority, the establishment of a government which should always withstand a popular storm such as that which the Germans established when they made all ministers dependent upon the crown, not upon the people. Our constitution-makers did the thing by checks and balances; Bismarck did it by saving to the king or emperor the essential power in the new state. The Federalists planned to train and discipline the people by their more adroit method; the Prussians were more happy in that their common men were not sufficiently conscious of their rights, and the German training has been easier and more effective.

If this explanation of the attitude of historians may suffice to show why Mr. Beard is unwelcome to scholars at one time and welcome at another, let us proceed to another point in our discussion of the interpretation of American history. Our author brings purely economic interests and motives to bear, and he shows how much they affected the great decisions of 1787-1800. The Constitution—the document par excellence of fluid property allied with the interests of owners of slaves— and the Jeffersonian reforms were but the items of a platform of the “interests” of landholders, including those of small farmers. With this view we may not, for the moment, find fault. But there were certainly other factors: a good woman of “old Virginia” once berated Jefferson because he had ridiculed the sacred vessels of the established church, and a great preacher hated “the reformer” because he had taught inferiors to hold their heads up in the world, to count themselves as good as other men, equal to the gentry.

Now this suggests that there are certain subtle social and religious influences which operate powerfully upon responsible men. I am sometimes puzzled to know why, for example, Peter Cartwright, who had denounced the slaveholders of the South for half a century, refused his support, in 1860, to Abraham Lincoln. Cartwright owned no slaves and he hated the slavery system. Lincoln proposed to curb the power of slaveowners and to do it in the most moderate and “constitutional” manner. Yet Cartwright stood aloof. There is something in the life of men, associated together for common purposes, which defies tabulation and which escapes the closest scrutiny of the historians who seek to show conclusively that a single cause produced certain results.

It is this condition or circumstance which makes history the most difficult as well as the most interesting of all studies and which makes the verdicts of the distinctively economic or political historian sometimes very doubtful. But Mr. Beard does not claim that his work is final; indeed, he openly avows that it is only fragmentary, that it is incomplete. One may wonder, however, whether by this he means that it is only a part of the economic determinism which all further research will tend to fix, or whether such factors as religious predilections or sheer personal will shall be taken into account.

Whatever is meant by fragmentary, it is certain that his work thus far has contributed a great deal toward the clearing up of the public mind on the epoch which he has described. These volumes are enlightening in ways in which few other studies of this period are enlightening. For example, chap, v of the Economic Interpretation of the Constitution gives a list of the members of the federal convention, and after each name an account of the economic and social affiliations of that individual. James Wilson, we are told, “removed to Philadelphia where he established a close connection with the leading merchants and men of affairs, including Robert Morris, George Clymer, and General Mifflin. He was one of the directors of the Bank of North America; and he also appears among the original stockholders of the Insurance Company of North America?’ Other similar accounts of all the leaders of the Federalist movement make up the chapter which concludes with a moderate statement of what would seem to be the logical conclusion: “At least five-sixths [of the members] were immediately, directly, and personally interested in the outcome of their labors at Philadelphia and were to a greater or less extent economic beneficiaries from the adoption of the Constitution.”

In the second volume of Mr. Beard’s work the economic character of the Washington administrations is clearly presented. It reflects the views of the majority of voters both in the national convention and in the state conventions which adopted the Constitution. None but true Federalists were put on guard, unless Jefferson be excepted—and a reference to unpublished letters of that leader now available show conclusively that he was as good a nationalist as Washington himself, though a Federalist in the true sense he was not. In the chapters treating the politics of agrarianism and the battle of 1800 we have the same kind of analysis which characterizes the former volume. Here the test is not the holding of stocks in banking or other corporations or government securities, but the ownership of lands or land warrants. The ownership of a plantation is also put down as a strong reason for voting the Republican ticket, which, as I have already indicated, may not be quite correct. John Taylor is made the philosopher of the party which came to power in 1800, nor does this seem to be wrong. Taylor was undoubtedly the theorist of the party of Jefferson, and Taylor’s ideal was undoubtedly the plantation interest. Yet whoever has read Taylor’s Arator will remember how he condemns the plantation management and especially negro slavery. There was thus something more in Taylor than the plantation “interest,” and it may be stated with more than plausibility that Jefferson and the small farmers and even the tenant class who made up the sentiment of Republicanism were far in advance of Taylor.

But without doubt the treatment of the Republicans which distinguishes the Economic Origins of the Jeffersonian Democracy is most informing. To know that land speculation and not the common good determined the location of Washington on the Potomac, that big planters made such a fight for their interests during Jefferson’s two administrations, that democracy could not get “a hearing,” or at least “ the right of way,” is enlightening. The picture of the Family Compact of Connecticut reminds one of the boss organizations of many of the states of today, while the analysis of the struggle in New York shows more clearly than we have ever known before what the issue between Hamilton and Burr really was. Still it is very doubtful whether the author is right when he attempts to prove, as he does on pp. 457-60, that Jefferson was at heart not democratic. The constitution which he proposed for Virginia in 1776 was certainly a much more democratic instrument than was proposed by any other prominent man of the time except possibly Franklin. It was seriously debated and not a mere matter of form.

If this should not be regarded as a sufficient test, one has only to turn to Jefferson’s lawmaking in 1776-77 for satisfaction. The real reason that a more democratic constitution was not adopted in Virginia during Jefferson’s lifetime is that the state was so opposed to anything like democracy. Not once but many times the old Republican denounced the system and endeavored to secure an improvement. It may seem strange to people not very observant of the ways of politics that the greatest of all Virginians could not even reform the constitution of his state. But such is the fact. It is not at all improbable that New York will cast its electoral vote this year for Theodore Roosevelt. Yet it would be impossible for Roosevelt to secure such amendments to the New York constitution as he regards essential to the welfare of the people of that commonwealth. New York, like Virginia a hundred years ago, is willing to vote for a man she hates in order to defeat some other man whom she hates more cordially.

These volumes call attention once again to the content of history. On this subject many have spoken. Yet another word may not be out of place. Possibly economic motives are the greatest in shaping the course of history; but next to these I should place religious motives. Then social and political influences count. And there is still another— the purely personal factor which sometimes determines the direction a nation shall take at a given crisis. How much in a given crisis is personal may be open to doubt, yet none will deny that purely personal will and stubbornness have contributed the decisive element, for example in the case of Andrew Jackson’s determination in 1830 to run a second time for the presidency and break the “understanding” with Calhoun and his friends, or in the crisis of 1870 when Bismarck recast the Ems dispatch in such a way as to bring on war between Germany and France.

If one were to make as careful study of the religious background of the American Revolution as Mr. Beard has made of the economic bearings of parties in the constitutional epoch, it would doubtless appear that the break with England and the Declaration of Independence were both to a large extent the results of long-growing discontent with the religious and social ideals of the ruling element in the mother-country. Surely the Presbyterian war upon the Establishments in the South was a factor, and the Baptist equalitarianism which was so prevalent in all the South was not without influence. In fact, we know that these factors entered into the politics of Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson; and these two men were for that region decisive in many matters of public policy.

Other influences may come to the mind of the reader, all of which should tend to make the historian cautious in determining and cataloguing the causes of certain important events and movements. What we have to do in the writing of history is to take into account the complexity of any given situation, examine into all the ascertainable influences that must have contributed to a certain result, and then do what Lamprecht, one of the most learned of modern historians, mistakenly said was the easiest thing in the world: simply describe what was going on. Tested by such a standard Professor Beard appears a little dogmatic; but since he only claims for his work the importance which attaches to the investigation of one series of facts, the reviewer cannot fail to say that his is one of the most important works of recent times. It does all he claims to have done, which is to call men’s minds to his side of the story and to warn them against the kind of writing which ascribes undue importance to political leadership. His two volumes have already aroused much discussion; they are certain to count very largely in the historical work of the future.