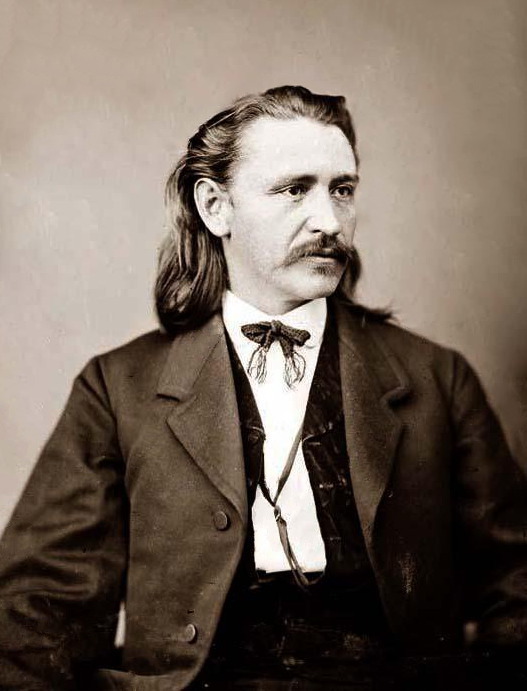

From the establishment of Jamestown in 1607, until the sundering of the Union, a period of roughly 250 years, English, and later American, governments had a very poor record in relations with Native American tribes. In 1861, however, a new “white” government emerged in the American South, the Confederate States of America. The new Southern Republic sought to gain an alliance with tribes of the Indian Territory, many of which once held ancient lands within the bounds of the new nation. One of these tribes was the Cherokee, and soon after hostilities broke out between the United States and the Confederacy, they cast their lot with the South. One of the Cherokee’s most able statesmen was Elias Cornelius Boudinot, who served as a lieutenant colonel in the Southern army and a member of the Confederate Congress.

Elias Cornelius Boudinot, who went by Cornelius, was born on August 1, 1835 near the present site of Rome, Georgia. He was the son of the famous Cherokee leader of the same name, Elias Boudinot, and a white mother from New England. His father, Elias, took his name from the revolutionary leader Elias Boudinot of New Jersey, whose boarding school he had attended and who had aided him financially.[i] Father Elias, whose original family name was Watie, edited and published the first Cherokee newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. He believed, along with other Cherokee, like Major Ridge and John Ridge, that the only way the tribe could survive in the United States was through assimilation and acculturation with whites. As a result of these ideas, they formed a pro-American faction known as the “Ridge Party,” and signed the Treaty of New Echota, which removed the Cherokee, on the Trail of Tears, to the Indian Territory, in what is today Oklahoma. For their actions all three were assassinated in 1839.[ii]

Young Cornelius was just four when his father was cut down in his prime. Without his father’s influence, he was raised and educated in New England among his mother’s family in Vermont, as fear spread among the Boudinots and Ridges that they themselves might also be a target if they remained in Cherokee territory. Receiving a first-class education in New England, Cornelius worked for a year as a civil engineer with a railroad company in Ohio. But, like many youths in the 1830’s, he set out to make a fortune in the West.[iii]

Whether out of fear or for some other reason, Cornelius Boudinot did not travel to his father’s ancestral homeland, the land of his birth, in the old Cherokee Nation, but instead settled in Fayetteville, Arkansas in the 1850’s. There he would be close to his father’s brother, Stand Watie, who lived nearby in the new Cherokee Nation, just over the Arkansas border. While in Arkansas, Boudinot studied law, passed the bar in 1856, and began editing a newspaper, the Arkansian. He was fast becoming a well-respected member of Arkansas society, especially in the realm of politics. In 1860, as “secessionitis” was germinating across the South, Boudinot was elected chairman of the Arkansas Democratic Party’s state central committee. After his election, he moved to the state capital of Little Rock.[iv]

In November 1860, the “Secession Crisis” finally came to a head when Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected to the presidency with less than 40 percent of the popular vote. Fire-eaters in the Deep South had long threatened to dissolve the Union should anyone hostile to Southern interests gain the White House. South Carolina did not waste any time, seceding on December 20 of that year. Mississippi soon followed on January 9, 1861, and by February 1, seven Southern states had voted in special conventions to leave the United States and form a new government. This new Southern nation was born in February and Jefferson Davis of Mississippi was elected its first president. Boudinot notified his uncle, Cherokee leader Stand Watie, that a Southern Confederacy had been formed in Montgomery. “Active preparations are being made to commence an attack on Ft. Sumpter [sic] and the attack and capture are considered a foregone conclusion,” he wrote, and, because of these actions, “State authorities at Little Rock have taken possession of the Arsenal there.”[v]

Arkansas and the rest of the Upper South, however, did not immediately join their fellow Southern states in disunion but instead waited to give Lincoln, and the U.S. government, at least a chance. Yet Arkansas decided to hold an election for a state convention for the purpose of devising a course of action. And, in a move that was surprising to many, the people of that state voted for a majority of Unionist delegates to attend the meeting slated for March 4, 1861, the day of Lincoln’s inauguration. At the convention, Boudinot was selected, by a vote of 40-35, to serve as the permanent secretary. As editor of the Arkansian, he had written editorials siding with the South in its case for establishing a Confederacy but in the convention he seemed to shift to the Unionist side, at least temporarily. On February 12, he had written Stand Watie informing him that John Ross, the principal Cherokee chief, “has published a letter in the Van Buren [paper] in which he says the Cherokees will go with Arkansas and Missouri.” It seemed as if that was Boudinot’s plan as well.[vi]

The delegates debated, argued, and pled with one another for nearly two weeks, mainly over the issue of whether or not secession was a legal act. Neither side seemed able to persuade the other. On March 16, the convention finally held a vote and, by a count of 39 to 35, secession failed. It seemed, at least for the foreseeable future, that Arkansas would remain loyal to the Union. Yet the convention remained in session, as the secessionists were pulling out all the stops to have their way.[vii]

Finally, the convention decided to adjourn and allow the people of Arkansas to decide for themselves in a referendum where their loyalties lay. In the plebiscite, they would be given a simple choice on the ballot: Secession or Cooperation. After the people had spoken, the convention would then reconvene to take the appropriate action. In the ensuing months, Boudinot made numerous stops around the state making speeches to educate the public on the issues concerning the current situation. He did not speak for or against either position but simply spelled out both sides of the argument.[viii]

The situation, however, changed dramatically on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor, South Carolina, as Lincoln was attempting to reinforce the federal installation. The next day, Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers to “suppress the rebellion.” Arkansas, still in the Union, would have to supply 780 troops to the Union cause under Lincoln’s plan. Governor Elias Rector refused. Judge David Walker, chairing the state convention, was under enormous pressure, given recent developments, to call the delegates back to Little Rock. In addition to the already extraordinary news, rumors were spreading rapidly that federal troops were poised to “invade” Arkansas and take Fort Smith. This proved to be untrue but it pushed many Unionists and fence-sitters to the side of secession.[ix]

The convention met in May and Chairman Walker hoped to accomplish two things. First, to pass a secession ordinance and officially leave the Union and, secondly, to gain control of the state government before the fire-eaters did. On May 6, the convention voted overwhelmingly to secede from the Union and join the Confederacy, with only one dissenting vote. However, the convention continued in session to rewrite the state’s constitution and take care of other pressing matters, such as establishing relations with the Confederacy. Boudinot remained in Little Rock as secretary of the convention and used his considerable influence in crafting a new state constitution. Several changes were made. For example, the old document used the phrase “all free men,” but the new one would read “all free white men and Indians.” The new Confederate state of Arkansas retained slavery but it included Indians as part of its citizenry.[x]

Once Arkansas joined the Confederacy, the government in Richmond wanted to extend its reach into Indian Territory to the west. The Confederacy concluded “Treaties of Friendship and Alliance” with the Cherokee, the Choctaw, the Creeks, the Seminoles, the Comanche, the Shawnee, the Seneca, and the Wichita, to name but a few. The Confederate government conducted a very serious effort to win over the Native American tribes. Secretary of War Leroy P. Walker wrote Douglas H. Cooper, agent to both the Choctaw and Chickasaw tribes, that the “desire of this Government is to cultivate the most friendly relations & the closest alliance with the Choctaw Nation and all the Indian tribes West of Arkansas and South of Kansas.” Those in the North, he wrote, “had its emisaries [sic] among the tribes for their ultimate distruction [sic]. Their destiny has thus become our own and common with that of all the Southern states entering this confederation.” Walker hoped to raise many Indian regiments to secure the frontier against possible Union army invasions. Cooper wrote President Davis that the Five Civilized Tribes “can furnish ten thousand warriors if needed” and “would be a terror to the Yankees.”[xi]

Boudinot hoped to be included in this new Indian army being raised to help defend the Confederacy. After the business of the convention had concluded, he left Arkansas and headed for the Indian Territory to join Uncle Stand Watie, who was busy building a Cherokee regiment of his own. Watie had already received word from friends that “President Davis is determined to arm the Cherokees, Creeks and Choctaws. Probably in the course of six or eight weeks there will be many guns for the Cherokees.” Boudinot had desires of achieving glory during the war, the same thoughts that filled the heads of countless others on both sides, and serving in a high-ranking position under his uncle was the surest ticket. In October he wrote Watie seeking the position of either lieutenant colonel or major in his uncle’s regiment. Boudinot begged his uncle for a chance:

You told me in Tahlequah [the seat of the Cherokee government] if I would go with you you would do a good part by me. I am willing and anxious to go with you and as you have it in your power to do a good part by me, and thinking without vanity, that I deserve something from your hands…. If any accident, which God forbid, should happen to you so that another would have to take your place, you will see the importance of having some one in responsible position to keep the power you now have from passing into unreliable hands.

Interestingly, Boudinot did not want anyone to see the length he went to secure for himself a high-ranking position, as he ended the letter by telling Watie to “Destroy this as soon as you have read it.”[xii]

Stand Watie did, indeed, commission Boudinot a major in the First Cherokee Rifles, and he served in that unit for more than a year, eventually rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. He fought in several major engagements, including Pea Ridge, and distinguished himself as a “gallant” fighter. But it was in the realm of politics that Boudinot would aid the Cherokees, and the Confederacy, the most.[xiii]

On August 21, 1861 the Cherokee legislature voted to secede and join the Confederacy. The Confederate Government soon established relations with the tribe in a “Treaty of Friendship and Alliance” signed on October 7, 1861 and ratified unanimously on December 23, 1861. Article XLIV of the treaty awarded the Cherokees one non-voting delegate to the Confederate Congress, with the first election to be held under the direction of the principal chief. This was a right and privilege that the United States Government would never have considered for any Indian tribe. With the pro-Union John Ross faction of the Cherokee nation scattered, pro-Confederate Cherokees seized control of the tribal government and elected Watie its principal chief and Boudinot to its seat in the Confederate House of Representatives on August 21, 1862. Boudinot traveled to Richmond later that fall and took his seat on October 9.[xiv]

Throughout the war, the Confederate Government under Jefferson Davis sought the very best friendship with all Indian tribes. By December 1861, after several treaties with numerous tribes had been signed, President Davis sent the Confederate Congress a message specifically regarding Indian relations. Imploring Congress to ratify them, Davis pointed out that each treaty gave the Confederacy “guardianship over the tribe” and the responsibility “for all obligations to the Indians imposed by former treaties on the Government of the United States.”[xv]

The President also sought to supply the nations with both materials and money, asking Congress to “advance $150,000, and the interest of $50,000 for educational purposes on what are known as the Cherokee neutral lands…which lands we guarantee to the Indians against the hazard of being lost by the fortune of war or ceded by treaty of peace.” In other words, Davis, who could trace his family lineage back to the great Powhatan chief Opechancanough, sought to do what the United States would not – honestly and judiciously take care of the Indian tribes under his jurisdiction.[xvi]

President Davis worked hard to care for all the tribes in the Indian Territory throughout the life of the Confederacy. He ordered the establishment of a Bureau of Indian Affairs, appointed an Indian agent for most of the tribes, and continually encouraged tribal leaders to stick with the Southern effort, even toward the end when it seemed all might be lost. “The welfare of the citizens and soldiers you represent,” he wrote Israel Folsom, president of the Grand Council of the Six Confederate Indian Nations, “is identical with that of all the Confederate States in the great struggle in which we are now engaged for constitutional rights and independence, and you are regarded by this Government as peculiarly entitled to its fostering care.”[xvii]

On August 18, 1862, the President wrote Congress that the “Indian nations within the Confederacy have remained firm in their loyalty and steadfast in the observance of their treaty engagements with this Government,” despite the fact that there had been delays in getting some of the promised aid delivered on time. And the nations seemed to appreciate his efforts and viewed him as a benevolent leader. One letter to President Davis from the Choctaw Nation addressed him not as “Mr. President” but as “Dear Father.” Here was someone Cornelius Boudinot could work with.[xviii]

Even though Boudinot was a member of the Confederate House of Representatives, he was, officially, a delegate only and could not vote. He was assigned to the Committee on Indian Affairs, an essential post, and was allowed, by rule, to draft and propose bills that directly affected the Cherokee Nation and to speak on their behalf in committee meetings and on the floor. However, Boudinot was clever enough to put a much more liberal interpretation on the privileges of a “non-voting member,” viewing it to mean that he could work on behalf of any issue that “affected” Indians in any way. This meant that he could involve himself in almost any issue he wanted.[xix]

Representative Boudinot cared deeply for the Cherokee Nation and the Confederacy. He sought to do all he could for both. While not in session in Congress, he traveled frequently to Arkansas and the Indian Territory to meet with Watie. He wanted to see first-hand the situation on the ground, as this “intelligence of the State of Affairs” would “enable me to do more at Richmond than I could otherwise.”[xx]

Yet he also was greatly concerned about the miserable conditions in the Cherokee Nation. By treaty agreement, the Confederate government owed a sum of money to the Cherokees and Boudinot wanted to see it paid. He wrote Watie that he intended to invoke the terms of the treaty that stipulated that the money could be paid to anyone that was authorized to receive it by the authorities in the Cherokee Nation. He would then see that it was distributed to those who needed it most. Boudinot was successful in this quest and the money, along with supplies, was paid to him for distribution. In early 1864, the Confederate Congress appropriated another $100,000 to the Cherokee Nation, from a bill authored by Boudinot and signed by President Davis, but this money, as with all the rest, was beginning to lose much of its value with run-away inflation, a problem that began to seriously plague the Confederacy.[xxi]

By 1864 and 1865 it seemed more and more likely that the Confederate States of America was beginning to unravel. But like President Davis, Boudinot continued to espouse confident feelings of ultimate victory. In July 1864, with Grant having crippled Lee and bottled him up at Petersburg, Virginia, Boudinot wrote Watie it was his view that the “cause never looked brighter and an early peace is universally predicted.” But within a year, the Confederacy had collapsed and Boudinot would be seeking another profession.[xxii]

With the end of hostilities in the spring of 1865, the United States sought to re-establish ties with the Indian tribes and Boudinot played a major role in those negotiations. He also partnered with Uncle Watie in a tobacco “factory,” which was quite prosperous. Yet he never let go of his “radical” views that in order to survive, the Cherokee need to let go of the past and embrace the future, or the ways of the white man. He even desired to see the Indian Territory become a state. Because of these views, he was hated in his final years, even receiving death threats. Cornelius Boudinot died at his residence at Fort Smith, Arkansas on September 27, 1890, an important, yet forgotten hero in the South’s “Lost Cause.”[xxiii]

*******************************************

[i] Elias Boudinot of New Jersey was a delegate to the Continental Congress, serving a term as president of that body, and later a member of the U.S. House of Representatives.

[ii] James W. Parins, Elias Cornelius Boudinot: A Life on the Cherokee Border (Lincoln, 2006), 4-15; Ezra J. Warner and W. Buck Yearns, Biographical Register of the Confederate Congress (Baton Rouge, 1975), 26.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid. The term “Secessionitis” comes from George Templeton Strong, a New York lawyer, who used it in his diary, which was edited by Allan Nevins.

[v] Boudinot to Watie, February 12, 1861, in Edward Everett Dale and Gaston Litton, Cherokee Cavaliers: Forty Years of Cherokee History as told in the Correspondence of the Ridge-Watie-Boudinot Family (Norman, 1939), 102-104.

[vi] Parins, Boudinot, 37; Boudinot to Watie, February 12, 1861, Dale and Litton, Cherokee Cavaliers, 102-104; Arkansas Ordinance of Secession, in War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (hereafter cited as OR), Series 4, Volume 1 (Washington, D.C., 1894), 287-288.

[vii] Parins, Boudinot, 38.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Parins, Boudinot, 38-39.

[x] Parins, Boudinot, 39.

[xi] L.P. Walker to Douglas H. Cooper, May 13, 1861, in Dale and Litton, Cherokee Cavaliers, 104-105; Douglas H. Cooper to Jefferson Davis, in Lynda L. Crist and Mary S. Dix, eds., Papers of Jefferson Davis, vol. 7 (Baton Rouge, 1992), 267.

[xii] A.M. Wilson and J.W. Washborne to Stand Watie, May 18, 1861, and Elias Cornelius Boudinot to Stand Watie, October 5, 1861, in Dale and Litton, Cherokee Cavaliers, 106-107, 110-111.

[xiii] Frank Cunningham, General Stand Watie’s Confederate Indians (Norman, 1959), 36, 51, 52, 58, 73; John M. Harrell, ed., Confederate Military History, vol. 10, part 2: Arkansas (Atlanta, 1899), 118.

[xiv] Treaty of Friendship and Alliance with the Cherokee Nation, in James M. Matthews, ed., The Statutes at Large of the Provisional Government of the Confederate States of America (Richmond, 1864), 394-411; Journal of the Confederate Congress, 611; Parins, Boudinot, 51-52.

[xv] Jefferson Davis, Message to the Congress of the Confederate States, December 12, 1861, in James D. Richardson, ed., A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Confederacy, vol. 1 (Nashville, 1906), 149-151.

[xvi] Jefferson Davis, Message to the Congress of the Confederate States, December 12, 1861, in Richardson, Messages and Papers, 149-151; Laurence M. Hauptman, Between Two Fires: American Indians in the Civil War (New York, 1995), 12.

[xvii] Jefferson Davis to Howell Cobb, March 12, 1861, in Richardson, Messages and Papers, 58; Jefferson Davis to Israel Folsom, February 22, 1864, in Dunbar Rowland, Jefferson Davis, Constitutionalist, vol. 6 (Jackson, 1923), 184-186.

[xviii] Jefferson Davis, Message to Congress, August 18, 1862, in Richardson, Messages and Papers, 238; Moty Kanard, et al. to Jefferson Davis, August 17, 1863, in OR, series 1, volume 22, 1107-1108.

[xix] Parins, Boudinot, 53; Warner and Yearns, Biographical Register, 27. Parins has a very negative view concerning the fact that the Confederate Government did not allow Indian delegates to be full voting members of Congress. But the Indian Territory was not a sovereign state and therefore could not have a full member (The U.S. Congress today does not allow delegates from territories to vote). It is not known if that area would have become a state or several states under a permanent government but at least the Confederate Government allowed them to join its Congress, which the Federal Government never did.

[xx] Boudinot to Watie, January 23, 1863, in Dale and Litton, Cherokee Cavaliers, 119-120.

[xxi] Boudinot to Watie, January 24, 1864, in Dale and Litton, Cherokee Cavaliers, 150-153; Parins, Boudinot, 54-55.

[xxii] Boudinot to Watie, July 13, 1864, in Dale and Litton, Cherokee Cavaliers, 181.

[xxiii] Warner and Yearns, Biographical Register, 27; Parins, Boudinot, 161.

Well done.

Great Job! The relations between the Confederate government and the tribes are an interesting and overshadowed part of our history. I hope to see more written about it in the future.