Increasingly, America’s past is becoming a lightning rod for contemporary ideological struggles. Colleges, highways and Democratic Party fundraising dinners are being renamed, monuments destroyed or desecrated, and a general suspicion seems to be growing of the value of anything emanating from America’s first century, soiled as it is with the stains of racism and slavery. This trend is a cause for concern among conservatives who value some elements of America’s past, especially as conservatives are increasingly being linked by their ideological opponents to these less admirable features of America’s history. Conservatives ought, therefore, to respond to such historical controversies with delicacy and tact if they are to separate themselves from the unsavory parts of our history, while still preserving what is good in it.

A recent essay by John Daniel Davidson on The Federalist, however, demonstrates the worst possible response to this situation.* When charged with being the ideological descendants of racists and bigots, Mr. Davidson suggests that conservatives ought to employ the classic retort of the ten-year-old: “I know you are but what am I?” Rather than offer a mature and nuanced defense of America’s past, they ought merely to turn the crude historical assaults back on their enemies. To that end, he claims that contemporary progressives – not conservatives – are actually the intellectual heirs of malicious Southerners and slaveholders.

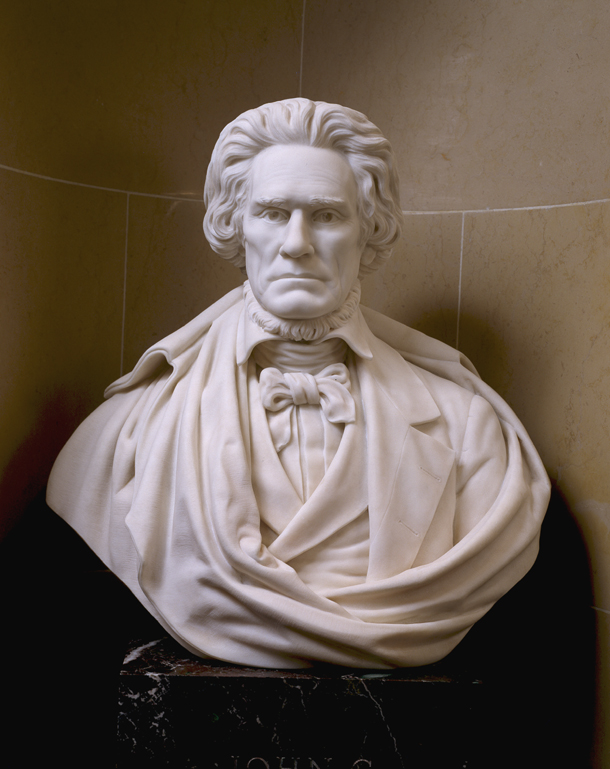

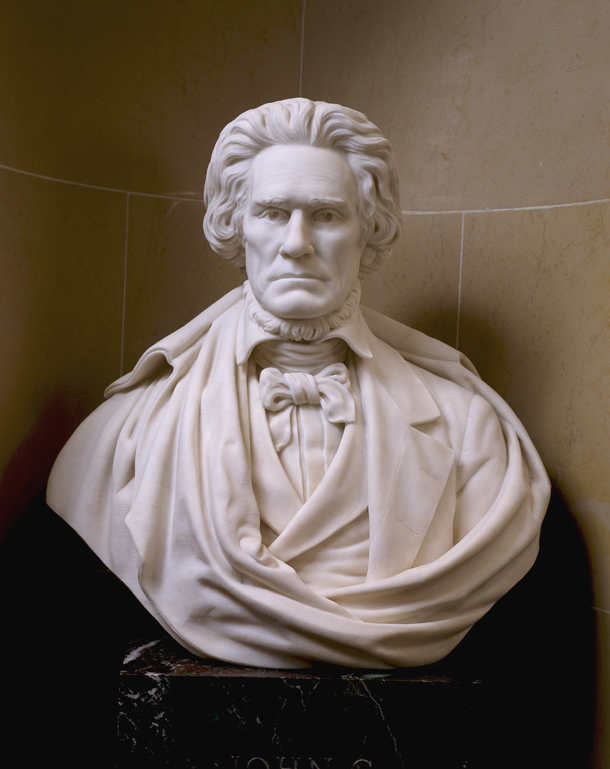

The centerpiece of Mr. Davidson’s assessment is his use of John C. Calhoun as universal boogey-man. Mr. Davidson tells us that Calhoun, known by those who have never studied him as a mere mouthpiece for the Southern slave interest, was the godfather of progressivism. He rejected Lockean natural rights in favor of “science,” (Mr. Davidson is not particularly specific about the content of this science, but he can be forgiven since it is nowhere to be found in Calhoun’s writings, either), and he saw history and circumstance as essential components of any calculation of political justice. Progressives also value social science and believe that political justice is susceptible to changes based on circumstance. Therefore, Calhoun was actually a progressive, and it is progressives who ought to be apologizing for their neo-Confederate ideology.

In assessing Calhoun, Mr. Davidson acknowledges his debt to the late Harry Jaffa, and indeed, since everything he says about Calhoun comes unfiltered from Jaffa’s A New Birth of Freedom, one might be forgiven for wondering if Mr. Davidson himself has ever read a word of Calhoun’s writings and speeches. It would be far too tedious to correct every one of Jaffa’s errors and misrepresentations that Mr. Davidson repeats, but a few are too egregious to overlook, as they serve to completely distort one of America’s greatest conservative thinkers.

First is the relationship between Calhoun’s thought and “science.” In A New Birth of Freedom, Jaffa claimed that Calhoun crafted a political theory based on modern science, which sought to conquer nature by manipulating human tendencies that can be observed through social science. Calhoun, however compared his political theory to a very different kind of science: astronomy. This study does not allow the scientist to conquer or manipulate nature. Instead, as Calhoun himself described it, astronomy “displays to our admiration the system of the universe.” Similarly, Calhoun’s science of politics sought to display to our admiration the social nature of man and all the human potential that emanates from that nature when fulfilled in a well-developed civil society.

Perhaps the most ridiculous claim in the essay is that Calhoun’s “general philosophy of government” was one that promoted “an active, pervasive government that doles out benefits, imposes vast regulations, and dictates our affairs based on ‘scientific’ principles.” Few statements could better demonstrate a complete ignorance of Calhoun’s writings than this. The concept of Calhoun’s “concurrent majority” theory was based on the observation that all governments have a natural inclination to expand their scope beyond their rightful limits; that there is a constant incentive for those who govern to misuse their power to advance their own interests. The purpose of government is to “preserve and perfect” the entire society over which it governs, and it can only accomplish that task if its role is limited by the elements which make up that society. It is pure fantasy to see in Calhoun’s thought any seed of a bloated administrative state.

Finally, Jaffa and Mr. Davidson claim that Calhoun’s theory of government was based on racial pseudoscience. This would not seem problematic to someone unfamiliar with Calhoun’s writings. After all, he is portrayed today as a theorist of white supremacy and slavery. But anyone examining Calhoun’s writings looking for a systematic theory of racism will be sorely disappointed. Calhoun undeniably reflected the racial attitudes of his time and place, and it is truly tragic that such an intelligent and, in other respects, virtuous statesman was so misguided and limited by America’s most prominent sin. Calhoun’s general theory of politics, however, had no racial component whatsoever. His greatest work, the Disquisition on Government laid out the elementary principles of free government. Slavery and race are nowhere to be found. In fact, in some key respects, the practical arguments he made about slavery unconsciously contradicted the principles found in that work. In his speeches on slavery and abolition, his racial attitudes emerge as completely customary and inherited. For a man of supreme intelligence, he seemed completely uninterested in intellectually justifying his racial prejudices. Looking back, Calhoun’s racial attitudes were deplorable, but he never peddled racial pseudoscience, nor was he a theorist of white supremacy. As such, those who share Calhoun’s conservatism or his belief in the principles of concurrent majorities, need not defend themselves from Calhoun’s vices any more than celebrants of the Declaration (Like Jaffa and Mr. Davidson) need to defend themselves from Jefferson’s slave-owning.

More is at stake, however, in Mr. Davidson’s distortions than the reputation of Calhoun. A main premise of Mr. Davidson’s essay is that someone who claimed to be a conservative (Calhoun) actually espoused the principles of progressive liberalism. Perhaps we ought to pause, however, to compare Calhoun and Mr. Davidson as conservatives: One recognized that majorities were not immune from the temptation to misuse power. The other places scare quotes around “tyranny of the majority.” One insisted that political justice and rights could not be boiled down to mathematical calculations, while the other applauds Earl Warren and William Brennan’s mathematical democracy as a cornerstone of our constitution. One recognized that political right draws its meaning from history and circumstance; the other claims that only abstract theories of liberté and égalité can justify a political regime. How did American conservatism reach a point at which the former beliefs are considered progressive and the latter conservative? If conservatives no longer recognize history, tradition, and restraints on majorities as their principles, and instead embrace abstract liberty, equality and majoritarianism, then an intellectual anarchy surely must have been loosed on American conservatism. Centers are not holding; falcons are not hearing falconers.

It was none other than Harry Jaffa who unleashed that anarchy on conservatism in the mid-twentieth century. The story of Jaffa’s impact on American conservatism has been told many times, and it need not be recounted again in great detail. But Mr. Davidson’s puerile assessment of America’s past shows the consequences of Jaffa’s new, ideological conservatism. Now that it has been absorbed by rank-and-file conservatives for over a generation, we can see just how destructive it can be to a genuine conservative outlook. Jaffa’s interpretation of the founding in the academic arena is simply incorrect; in the political arena, it threatens to undermine all forms of conservatism.

Jaffa’s great project was to build a kind of conservatism on the principles of liberalism. He was most successful in convincing conservatives that if they did not accept universal abstract principles observed through reason as the foundation of government, they were embracing moral relativism. As such, the particularism which defined conservative thought must be abandoned in favor of a specific set of universal principles which Jaffa found in the Declaration of Independence and Lincoln’s “refounding.” Traditional conservatives, of course, were not embracing relativism. Following Burke, they believed that long-established political and social orders are the framework which give any individual the ability to perceive, ever so dimly, the eternal and divine justice which is beyond the capacity of any human to fully comprehend. Abstract justice is always reflected and refracted in innumerable ways within a specific context before it can be comprehended by the human mind. Political and social institutions, therefore, ought to be conserved, not because they are perfectly true and right, but because their destruction would lead to political and moral anarchy. Jaffa, however, like progressive liberals, argued that institutions, however old and venerable, can be justified only through a direct comparison to abstract theories of liberty and equality. These ideas can succinctly be labelled the American Idea.

Jaffa’s reorientation of American conservatism has done considerable damage to the ability of conservatives to assess intelligently and appreciate America’s history. It has created a kind of founding myth which has, in turn, caused a tendency toward hero-worship among conservatives. There is an undeniable arrogance in the belief that America’s founders were the first (and perhaps only) in history to have founded their nation on true principles. America’s laws did not arise like those of every other nation, through history, compromise and gradual development, but were handed down, as it were, from the gods. One can see this in Jaffa’s attack on Calhoun’s belief that constitutions are the result of the careful, prudent deliberation of wise but fallible statesmen, making practical calculations about the situation before them. Jaffa and Mr. Davidson present this view of constitutionalism as “irrational” and “mindless.” Only those who, like the (capitalized) Founding Fathers, had access to abstract truth can create a legitimate constitution founded on the solid rock of reason.

This ideological view of American history also gives rise to a more general moral illiteracy among conservatives which rivals that of statue-demolishing liberals. Any personal vice or wrong-headed principle in our heroes threatens to demolish the founding myth. As such, rather than tactfully recognizing the failings and limitations of our founders, conservatives have developed a tendency to deny that they ever possessed those faults. Furious defenses are mounted to show that all Founders were virulently anti-slavery, possessed no limited or parochial views, and were never influenced by personal advantage. Furthermore, anyone who did have such tendencies must be dismissed as unimportant to the American Idea, whatever their contribution to American life may have been. What makes a figure virtuous, by this view, is the conformity of a person’s actions to the true American faith. America’s past, therefore, is a simple morality tale in which there are clearly discernible heroes who reflect purity of motives as evidenced by their complete devotion to Lockean natural rights, and villains who undermined those principles in the name of relativism, selfishness and immorality.

Conservatives may be particularly tempted to embrace this concept of America as an idea when responding to the racial reactionary elements of today’s ideological fringe. As such groups celebrate with growing confidence the worst tendencies of American history, what better way for conservatives to distance themselves from such ugliness while still salvaging our past than by removing as “un-American” those figures which seem most problematic? While such a solution may seem easy, it is both intellectually dishonest, and disastrous for conservatives. As poetic as the American Idea may seem, one cannot avoid the simple fact that a polity is composed of the people who make it up, and it must bear the stains of their evils along with the luster of their achievements. Treating racism as an un-American tumor on an otherwise pristine body truly understates the problem. The greatest tragedy of America’s past is that racism was present not only in its worst villains, but also in some of its greatest leaders, thinkers, and public figures. It cannot be cured by surgically removing a specific set of villains. This historical reality cannot be hidden behind glimmering visions of the American Idea. Those who seek to discredit all of America’s history, traditions, and institutions will expose this truth and utilize it to the advantage of their revolutionary programs. By way of an example, one might note Harvard president Drew Gilpin Faust’s recent suggestion that the right to free association is little more than a dogwhistle for bigotry and exclusion because it was utilized by Southern resistance to school desegregation. Almost anything emanating from deep enough in America’s past can be connected to racism in some manner, and this fact will be exploited. Only a moral discretion capable of demonstrating how virtue and vice live together in every society and, indeed, in every individual, can protect what is good in America’s history, traditions, and institutions from such an attack.

A more genuine conservatism, unlike Jaffa’s innovations and progressive liberalism, can provide that discretion by more truthfully and subtly assessing America’s past. By rejecting abstract ideology, conservatives stress the importance of learning the lessons history teaches us, rather than using history to prove the points our ideological commitments demand. Conservatives do not fight to preserve our institutions because they are perfect—because they were crafted by pure, god-like Founders, or because they reflect the one, true political faith. They preserve them because they have promoted a relatively free and steady political order for hundreds of years, and have served as a stable framework for our understanding of liberty, rights and justice. Like all constitutional structures, they are the product of compromise and conciliation among diverse groups with differing ideas and motivations. The men and women who have shaped them possessed virtues and vices, and their vices do not nullify their virtues. To the extent that conservatives reject this humbler and more moderate assessment of the past, they will find themselves incapable of adequately defending the historical figures, peoples, and institutions which they appreciate and memorialize as each comes under assault. The inconvenient truth is that America, like all other nations, is the product of both selflessness and selfishness, virtue and vice, wisdom and foolishness. If we reject the important historical figures who possessed the latter along with the former qualities, we must ultimately reject them all. Given this reality, conservatives cannot attempt to turn liberal attacks around on their adversaries. They cannot resort to using American history for the purpose of intellectually vacuous name-calling. They must approach history in a more nuanced and truthful way. It won’t matter that one puts Calhoun in the villain category if Jefferson still stands among the heroes. If the statues of Calhoun fall, the statues of the Declaration’s author will eventually fall as well. At that point, conservatives will need to worry about the preservation of more than just symbols, but also of laws, traditions, and treasured institutions.

Calhoun’s greatest contribution to American political thought was his observation that a people cannot be adequately represented simply through majority-rule elections. A society is not a mere collection of individuals—it is a unique, historical creation composed of a variety of groups and interests which often clash, but which nevertheless have moral obligations to each another. A government actuated by the whole, not just a part, of society will preserve and protect that society by encouraging civil harmony, conciliation and justice. His theory is not irrelevant to contemporary politics. It is also undeniably conservative in its character. Does this mean that conservatism is indelibly stained by Calhoun’s defense of slavery? Certainly not. All ideas, like all political institutions, have been crafted by flawed individuals. We cannot reject and debase the positive contributions, virtues, ideas, and examples of figures who had moral failings, even serious ones. A subtle and nuanced view of history would allow us to memorialize such elements of our past without a false pretension that vice did not exist alongside virtue. Let us approach our history as becomes thoughtful citizens, learning its lessons rather than fitting it into the procrustean bed of our favored ideology.

This essay was originally published at The Imaginative Conservative.