On a late November evening in 1970, I rolled into the “Big Easy” on an L&N freight with my pockets jingling. Hitching a ride to Canal Street – and letting the morrow “take thought for the things of itself,” as the Scriptures say – I checked into the Sheraton Delta Hotel, got myself cleaned up, then indulged myself in a supper consisting of Cornish hen, mushrooms stuffed with crabmeat, and hearts-of-palm salad – all washed down with a bottle of Beaujolais. Next, I went down to Bourbon Street to see if I could find any way to spend the rest of my paycheck.

Being a traditionalist it did not take me long to find Preservation Hall, which was around the corner from all the tourist hoopla. I paid a dollar to get in and stayed until they closed at half-past midnight. De De Pierce’s band was playing that night, and during one of their breaks I offered them four bucks to play “Lonesome Road” and “The St. James Infirmary Blues.” It remains one of the best investments of my life. With but few benches, chairs, and orange crates along the wall upon which to sit in the dim, smoky room, the crowd had mostly to stand – and the place was full. There was no bar or any other frills, just one bare light bulb hanging from the ceiling, beneath which old mahogany-colored men of an indeterminate vintage played blues and Dixieland like they were born to it!

I soon found the old brick fireplace with the raised hearth in the back of the room, and I was to spend many a night behind the crowd sitting on that hearth in the dim light with a bottle of Boone’s Farm apple wine tucked under my Navy pea-coat:

Look down, look down that lonesome road

Before you travel on….

I got back to the hotel room about 5:30 in the morning and slept until check-out time that afternoon. I woke up nearly broke again, so I checked into the Ritz on the lower end of Canal Street. It was a little more realistic arrangement: $5 per night, bathroom down the hall. You stepped off the street and went directly up a flight of wooden stairs. The man behind the desk was named Joe, and he wore a flat hat and wire-rimmed glasses. Whenever I would come in I would find him reading the Racing Form. He and I became friends, and the Ritz became sort of a “home away from home” for me to come back to whenever I went off on my subsequent rambles hither and yon.

Once again it was getting to the point where I had to find some work pretty quick. I found that one could make a day’s pay unloading trucks, so I went down to the warehouses along the river to see if I could find one. No luck. I next went over to the French Market, where produce trucks would come in and people had an open-air market going on. I got to talking with some Black men who were standing around on the corner. They said the way to do it is to catch the Tulane Avenue bus out to the truck terminal by the airport early in the morning and talk to the drivers when they go into the restaurant to get breakfast. They also advised me that I was paying too much money staying at the Ritz and that I ought to find a deserted house or warehouse to sleep in like they did.

One of the men informed me that there was a lot of fast money to be made in New Orleans. If you got hard up you could get yourself a gun. Pointing to a tourist as an illustration he said, “That White man over there has got a lot of money.” He then told me he had to stay up until after midnight that night, when he was going to go over and get this woman from another man and take her out of town somewhere. He said he had a gun with him and that he was going to put a “hurtin’” on the other man.

His companion – the one who had advised me about the accommodations at the warehouse wherein he resided – bummed a smoke off me and went back to sleep. Another eyed a cigar butt by the curbing, thumped the ashes off the end of it, and popped it into his mouth like a plug of chewing tobacco. Further down, at the other corner of the building, three of their associates were having a heated argument. My friends informed me they were always arguing about something, and this time the topic was wine.

Next morning early I caught the bus out to the truck stop, where I found a crowd of Black men standing around a fire barrel waiting for the drivers to emerge from their sleepers. I joined them, and I eventually found some work in spite of the stiff competition.

The trucks carried around 40,000 pounds of every sort of cargo imaginable. I once unloaded twenty tons of popcorn – and turned down a load of dumbbells going to Beaumont. I got a city map and learned how to pilot the drivers through town so they wouldn’t get lost or get a ticket for getting off the truck route to their destinations. A driver could always unload his own truck, but some loading docks had their own crews and they didn’t allow the drivers to bring in their own man. The exception was when a truck had a pair of drivers for running around the clock – not usual, maybe, but I suppose such a team would be pulling watches, like men at sea. But even in that case there could be trouble – or at least a hassle – as we found out one day.

I had gone out to the truck stop at 2 a.m. with $3 in my pocket. The last driver to wake up offered me $20 to unload his truck – which carried 41,000 pounds of potatoes from Minnesota packed in 100-pound sacks. When we got to the warehouse there was a sign that said no outsiders were allowed on the dock to unload, so I was suddenly promoted to “truck driver.” The driver filled me in on the past particulars of the run and backed me up when the people quizzed me on our trip and asked me why I was doing all of the unloading. I told them about loading in Hollendale, Minnesota, on Saturday morning, and about the 36 hour trip down. I explained to them how we took turns: I’d unload this time, then he’d unload the next. There were a lot of big men gathered around who were interested in my story, but they let it ride. They did, however, make us wait around until the middle of the afternoon before we got a spot at the dock. Because we weren’t using their men to unload the truck, ours was the last to get unloaded.

At noon the driver advanced me $5 so I could go around and pay my room rent for that day. When I came back I brought along a sack of hamburgers for our lunch and we watched the Black dock hands play a card game called “pitty-pat” in the back of an empty van. There was tall and lanky George sitting on an orange crate with a quarter stuck in his ear; “Rabbit” with his maroon and green baseball cap on sideways; Alphonso with his Tiparillo cocked at a jaunty angle, etc., all talking at the same time, laughing heartily, and throwing change and dollar bills into the pot. I don’t know who won, much less do I even have any idea how to play, but it kept things lively and interesting around there until we got to the dock and got unloaded. Twenty tons and a half – I never took much to potatoes after that.

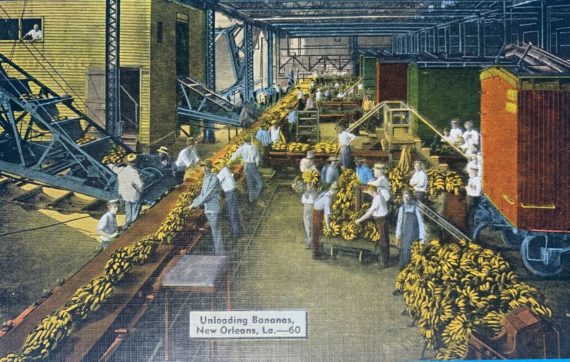

The driver paid me and was then generous enough to buy us both a supper of crawfish gumbo at the French Market. Afterwards I gave him directions on how to get on US 90 east to Gulfport where he was to pick up a load of bananas, and we parted company.

I have always thought I was born under a lucky star. The next day, walking down Canal Street, I bumped into a girl from home. I had just unloaded a truck for twelve dollars and I was still in my grubby clothes, but she hugged me anyway and invited me to Thanksgiving dinner at her apartment in the French Quarter, which she shared with two other girls. She told me she was working at a bank there in the city. I readily accepted, and of course it was a memorable repast. Afterwards she and I went down to Preservation Hall and heard Kid Thomas, who garnished his musicianship with a remarkable display of showmanship. When things started to get hot he put on a big red floppy hat, stood up in his chair, and made his trumpet talk trash until he brought down the house.

The next day I caught a two-day job with a furniture moving van. The driver was going to pay me $50. The first day we only cleaned out the van and folded the quilts, for which he gave me $15 of my pay. The next day we loaded furniture. Physically it was a hard day’s work. In addition, it required a lot of thinking. You had to get all the furniture packed into the trailer without dinging anything; you had to figure out what was going to go on the bottom and what could be stacked on top of what; you had to get the stuff out of the house in the order you wanted to load it, and all that. The driver was the owner/operator, and he said he was looking to get out of the business. He wanted to know if I was interested in working with him with an eye to maybe eventually buying him out. I told him I didn’t think I was ready to make such a commitment at that time, but I appreciated the offer.

Although I certainly did not tell him so, I did not relish the idea of owning – or being owned by – any mill stones, white elephants, or other dependency-generating devices designed for grinding out a regular living. Nor did I relish the idea of cluttering up my mind with all the sorts of thinking that would have to be involved. While captains, kings and CEOs are free to build castles on solid ground, they wear crowns that don’t rest lightly on their heads. Plus, they are always having to pull maintenance on the castles. On the other hand, while servants, poets, and vagabonds are not able to build them on the ground, they are free to build castles in the air because their minds are free. It is the paradoxical freedom of servitude, and a question of priorities.

But notwithstanding all of his prosaic mental burdens, I found that this furniture-moving truck driver had enough freedom-of-mind to delve into some serious philosophy. It was he who introduced me to the works of Immanuel Velikovsky. Worlds in Collision hypothesizes that the earth experienced two cosmic cataclysms within the recorded memory of man – once at the time of the Exodus and once at the time of the fall of Troy. Velikovsky presents as evidence the records, myths, folk-memories and legends from peoples around the world, and shows how they meshed in time. He argues – for example – that the passage of a comet within the gravitational field of the earth and the passage of the earth through the comet’s tail accounted for the plagues of Egypt, the parting of the Red Sea, and the pillar of smoke by day and fire by night recorded in the Book of Exodus. He caused such a furor in some quarters that the publisher was threatened with a massive boycott.

Velikovsky did not blink – and evidently the publisher did not, either. When some scholars pointed out that Velikovsky’s hypothesis was false because of a gross discrepancy in his timeline compared with the traditional Egyptian and Hebrew chronologies of the Bible, he published Ages in Chaos to challenge these chronologies. Using the cataclysm during the time of the Exodus as the point of departure, he reinterpreted the evidence presented in the ancient writings to bolster his conclusions. This was not all. Velikovsky then went on to publish Earth in Upheaval, which presented the strictly geological record that further substantiated his hypothesis.

With this rewriting of fundamental history, one may imagine the reaction among not only those whose faith was being challenged by it, but among those many scholars and theologians whose careers rested upon the very foundation this argument was threatening to destroy. I once asked a professor of the Old Testament whether he was familiar with Velikovsky. He said that he was – and that as far as he was aware, Velikovsky’s argument had never been proven wrong.

I cannot vouch for the veracity of any conclusions one way or another, but Velikovsky’s works revolutionized my thinking and philosophy and marked a paradigm shift in my world view as profound as any that had shaken the Age of Faith during the eighteenth century. I had earlier become a skeptic when it came to religious dogma and religious faith, but I had not filled the void my skepticism had left me with anything of value. Whether or not Velikovsky’s conclusions were true, I felt that the Revealed Theology that I questioned might be either refuted literally or substantiated allegorically with an understanding of a Natural Theology first suggested to me by Velikovsky’s work. And when I think about that, I think of that truck driver in New Orleans who opened that first door.

This opening began to pose for me some questions not only in matters of Faith, but also in matters pertaining to the Brave New World of Reason. The first – the Perennial Question – is: where did we come from and why, and where are we going with our heads so full of calculations and our souls so full of emptiness? We have not destroyed religious things with our totalitarian secular humanism, but we have destroyed plenty of secular things, if that is any consolation.

Another question: how do we explain the limits that we have encountered in the cosmos? These limits (like the speed of light and the square root of minus one) that seem to suggest that before we go rocketing off in neutrino-powered space ships beyond the boundaries of the speed of light we might have some more important things to attend to in our own back yard – things such as those revealed to us by the wisdom of the prophets or the rishis or the scriptures of all the exoteric traditions; Holy things, all of which exhibit a transcendent esoteric unity.

Furthermore, if these limits define the boundaries of the universe, then we are faced with a contradiction in terms. In that case the “universe” thus bounded is by definition not the universe, but a closed system within something else that is beyond. In classical physics closed systems are governed by the Second Law of Thermodynamics – a law which carries within itself a theological implication. The Second Law states that in a closed system energy tends towards entropy and not the other way around. In such a system, clocks and universes wind down on their own, but not up. This poses the next question (and the answer depends upon how we frame it): If we ask how things got wound up in the first place, we are getting into quantum theory and relativity theory. If we ask Who wound things up in the first place, we are getting into theology. And if we ask how the two are reconciled, we are getting into Fritjof Capra’s The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism, perfectly articulated in the Dance if Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction and regeneration.

And finally, if the universe is a closed system, then what lies beyond? Infinity turns the universe into a grain of sand, and looking up at the stars and trying to figure out how far “up” goes will give you a koan to meditate upon from now until Kingdom Come! As Thomas Carlyle wrote:

We sit as in a boundless Phantasmagoria and Dream-grotto: boundless, for the faintest star, the remotest century, lies not even nearer the verge thereof…. Think well, thou too wilt find that Space is but a mode of our human Sense, so likewise Time; there is no Space and no Time: We are – we know not what; – light-sparkles floating in the aether of Deity! …

December had arrived and I was getting restless. I could scratch up a few bucks in New Orleans, but (aside from the revelation that I had received from my introduction to Velikovsky) I was still a long way from fulfilling my quest for the Truth. Somewhere from beyond the din of the city – perhaps by the mighty river sweeping past the foot of Canal Street – I had heard the empty places calling.

I had a set of seaman’s papers for entry level ratings: Ordinary Seaman for the deck, Wiper for the engine room, and Food Handler for the stewards department. I had gone down to the union hall towards the end of November to see about a berth. Being particular, I had already ruled out accepting a job in the stewards department, although I had been told that was the quickest way of getting a berth. However, there were no calls for any entry ratings of any sort, so I went over to the Scandinavian Shipping Office where they said I might be able to ship out as a “deck boy” on a Norwegian tanker named the Brimstone that was due in soon. There was a possibility, but I scratched that right off. I would be glad to sail as a deck hand, but I had no intention of sailing as anybody’s deck boy! A Gentleman of the Road has his standards!

At some point in my sojourn in New Orleans I had gone out to the race track looking for work around the stables as a “hot walker.” Although I did not find work, I did take to going to the races some evenings and placing two dollar bets. I didn’t know anything about picking the horses, but I started betting on the jockeys who were regularly in the running. I’d check the odds on the horses they were riding, then bet on them to place or show if the odds weren’t too outrageous. In this way I pretty much broke even or even picked up a few bucks, but in any case it allowed me to have some fun without it costing too much.

But now it was time for me to leave town, and the race track was part of my exit strategy. I had my pay from the moving van job, so I went out to the Fairgrounds and bet $20 on Charlie Junior to win. He was the favorite in the ninth race and my jockey was riding him. Figuring I was bound to win some money, I planned to get a steak dinner afterwards, then get my grub for the road and catch out for the West Coast.

Lesson #1 in the search for the Truth: Don’t count your chickens before they hatch. I could tell my chickens weren’t going to hatch as soon as they left the gate. Right away Charlie Junior took the lead – which is something my jockey had never done before. He usually held his horse and let some other pace him until the last turn. Then he’d give the horse his head and let him run. Charley Junior held the lead through the back stretch and into the last turn, then he started to fade. I remembered my friend at the French Market telling me that there was some fast money to be made in that town and I wondered if somebody had thrown the race.

Needless to say, I did not get that steak dinner. I took what I had left and bought a loaf of bread, a big pack of bologna, a little thing of mustard, and an onion – ingredients with which I made a whole loaf of bread’s worth of bologna and onion sandwiches. I had figured I could make it to the West Coast and back on this and $30. Now I had to do it with this and $2.

But I had to go, and before I left I wrote a poem and sent it to my hometown friend who had invited me to share Thanksgiving dinner with her and her roommates. As poems go it is pretty horrible, but as an expression of the moment it was heartfelt:

Suddenly, too many

Feet, faces, open mouths.

The good guitar goes bad.

The beer turns warm and costs too much.

I smoke cigarettes,

Each one worse than the last.

In the street there is no change:

Hot spot hawkers open their doors,

Giving glimpses of dancing girls

To hustle you into Paradise;

Bumper to bumper, every car

Blows a horn, herding people.

In the chilly darkness

I hurry down to the train yards

And think of warmth I left behind.

Hiding from the railroad men,

I watch a freight train

Labor onto the high-line.

I dive into a boxcar,

Then stand in the door

To watch the lights of the highways

And juke joints drift away.

I wave to a car at the crossing;

You’ll never be free, Mister!