What do a popular country group and the Vanderbilt Agrarians have in common? West Virginian Arlos Smith penned the song Mayberry for the pop-country group Rascal Flatts. There are striking similarities between the Agrarian manifesto I’ll Take My Stand (ITMS) and the song Mayberry, but I couldn’t find any evidence that the work of the Agrarians had any influence on the writing of the song. It just may be that this song organically sprang from the same fertile Southern soil and traditions as the work of the Twelve Southerners. It’s ironic that Nashville is associated with the Agrarians then and with country music now.

For brevity, I will leave out the background nananana’s and quote only the pertinent lyrics from Mayberry. The song begins:

Sometimes it feels like this world’s spinning faster

Than it did in the old days

So naturally, we have more natural disasters

From the strain of a fast pace

Sunday was a day of rest

Now, it’s one more day for progress

And we can’t slow down

(And we can’t slow down)

‘Cause more is less

(‘Cause more is less)

It’s all an endless process

Progress for progress’ sake is not necessarily progress, as the Agrarians and Mayberry proclaim. A faster pace may not get you where you want to go. Today we often hear the phrase 24/7, yet we need to stop and think about this concept. Not only is Sunday not the ‘day of rest,’ but there often is no day of rest for production. It may truly seem to be ‘an endless process.’

John Crowe Ransom, in his ITMS essay, “Reconstructed But Unregenerate,” attempts to pin down this idea of progress:

“This is simply to say that Progress never defines its ultimate objective, but thrusts its victims at once into an infinite series. Our vast industrial machine, with its laboratory centers of experimentation, and its far-flung organs of mass production, is like a Prussianized state which is organized strictly for war and can never consent to peace.”

Lyle H. Lanier, in his contribution, “A Critique of the Philosophy of Progress,” echoes these sentiments:

“A steady barrage of propaganda issues through newspapers, magazines, radios, billboards, and other agencies for controlling public opinion, to the effect that progress must be maintained. It requires little sagacity to discover that progress usually turns out to mean business, or else refers to some activity which serves to allay the qualms of the business conscience. General sanction of industrial exploitation of the individual is grounded in the firm belief on the part of the generality of people that the endless production and consumption of material goods means “prosperity,” “ high standard of living,” “progress,” or any one among several other catchwords. The conviction that our noisy social ferment portends progressive development toward some highly desired, but always undesignated, goal is perhaps the central psychological factor in the maintenance of our top-heavy industrial superstructure.”

Industrializing agriculture is an example. It has led to major problems: depletion of soil, lack of nutrients in our food, poor food quality and the resultant myriad health problems we suffer from today. That doesn’t sound like progress.

The introduction to ITMS, likely written for the most part by John Crowe Ransom, has this to say about the future of a consumer society:

“Turning to consumption, as the grand end which justifies the evil of modern labor, we find that we have been deceived. We have more time in which to consume, and many more products to be consumed. But the tempo of our labors communicates itself to our satisfactions, and these also become brutal and hurried. The constitution of the natural man probably does not permit him to shorten his labor-time and enlarge his consuming- time indefinitely. He has to pay the penalty in satiety and aimlessness. The modern man has lost his sense of vocation.”

Donald Davidson, in his essay “A Mirror for Artists,” has more to say on the effects of a hurried pace:

“It is common knowledge that, wherever it can be said to exist at all, the kind of leisure provided by industrialism is a dubious benefit. It helps nobody but merchants and manufacturers, who have taught us to use it in industriously consuming the products they make in great excess over the demand. Moreover, it is spoiled, as leisure, by the kind of work that industrialism compels. The furious pace of our working hours is carried over into our leisure hours, which are feverish and energetic. We live by the clock. Our days are a muddle of “activities,” strenuously pursued. We do not have the free mind and easy temper that should characterize true leisure. Nor does the separation of our lives into two distinct parts, of which one is all labor–too often mechanical and deadening–and the other all play, undertaken as a nervous relief, seem to be conducive to a harmonious life. The arts will not easily survive a condition under which we work and play at cross-purposes.”

Andrew Lytle, in his essay, “The Hind Tit,” ponders how the high expectations of the founding of the American Union had not been realized, and the commonwealth had gone astray:

“There are those among us who defend and rejoice in this miscarriage, saying we are more prosperous. They tell us–and we are ready to believe–that collectively we are possessed of enormous wealth and that this in itself is compensation for whatever has been lost. But when we, as individuals, set out to find and enjoy this wealth, it becomes elusive and its goods escape us. We then reflect, no matter how great it may be collectively, if individually we do not profit by it, we have lost by the exchange. This becomes more apparent with the realization that, as its benefits elude us, the labors and pains of its acquisition multiply.”

He then goes on to make comments which seem to fit our time as well as a century ago:

“Since 1865 an agrarian Union has been changed into an industrial empire bent on conquest of the earth’s goods and ports to sell them in. This means warfare, a struggle over markets, leading, in the end, to actual military conflict between nations. But, in the meantime, the terrific effort to manufacture ammunition–that is, wealth–so that imperialism may prevail, has brought upon the social body a more deadly conflict, one which promises to deprive it, not of life, but of living; take the concept of liberty from the political consciousness; and turn the pursuit of happiness into a nervous running-around which is without the logic, even, of a dog chasing its tail.”

Here we return to the lyrics of the song:

I miss Mayberry

Sittin’ on the porch drinkin’ ice cold cherry coke

Where everything is black and white

(Nana nana nananananana)

Pickin’ on the six string

People pass by and you call them by their first name

Watchin’ the clouds roll by

Bye, bye

Whether 1930 or 1960, people in the South, exemplified by the television show Mayberry, certainly knew their neighbors. Sitting on the porch would have been a common pastime, though with the advent of television, these times were growing fewer. Everything was black and white could refer to older television shows, which were much more family friendly. It could also refer to distinctions being more sharply defined. There were two genders, a concept very simple to understand in days past. You may remember, as I do, watching clouds going by. Such exercises bring us closer to nature. Though we get our forecasts from scientists today, close observations of nature married with traditions were what most generations have relied on to seek tomorrow’s forecast.

“Pickin’ on a six string” reminds us of the warning Andrew Lytle issued concerning the radio. (In 1930, television was still a few years in the future) Take the fiddle down from off the mantle-not quite, but almost strummin on a 6 string. Often that fiddle would be accompanied by a six string, a banjo or mandolin. In the hollers and at the crossroads store, cabin porches and hoe downs, jigs and reels, cloggin, square dance… The Agrarians and those they wrote of would still feel at home in many rural places today. The forms of art would be familiar, if not the worries of modern life. Neighbors usually not only knew each other, but looked out for one another.

There is a small town in Mississippi, which I remember visiting often on Saturday mornings long ago. Men came in from the countryside in their overalls. They sat, talked, and whittled. I’m sure they watched clouds roll by on occasion. Recently I went back through that town, but that form of leisure has passed. Only the roar of freight trains fills the square now.

Sometimes I can hear this old earth shoutin’

Through the trees as the wind blows

That’s when I climb up here on this mountain

To look through God’s window

Now I can’t fly

But I got two feet that get me high up here

Above the noise and city streets

My worries disappear

Worries disappear as the singer gets farther from streets and noise, from the city. Living in the shadow of the Great Smoky Mountains I see many people who have driven a long distance to “climb up here on this mountain.” It is sad that many come for the shopping, entertainment and food, rarely getting out of their cars to even take a few pictures. Those who do get out, even for a short hike, probably enjoy more leisure and stress relief than those making the rounds of the tourist traps.

If you think your lifestyle is improved by having more things, he who has the most toys wins, you are sadly mistaken. What does it profit? This is not to say that improving life is not good. It is good when limited by the practical dictates of a well rounded life.

Think of the worries which are tied to the noise and city streets……traffic jams, road rage, breakdowns, wrecks…..call the insurance, total the car, ….stress! In years long past, if a wagon was damaged, you often could fix it. No insurance, a little sweat and some parts. Cars require much more maintenance, and if one has a serious breakdown, he can’t unhitch the horse and make it back home. Technology leads to dependency. Of course, many will say you can’t turn back the clock, and in reality we probably would not want to. But songs like Mayberry strike a chord in our memory, and the ‘good ‘ol times’ were probably better in many ways than people sometimes think. We should seek more balance.

Sometimes I dream I’m drivin’ down an old dirt road

(Down an old dirt road)

Not even listed on a map

(Ooo, yea)

I pass a dad an’ son carryin’ a fishin’ pole

But I always wake up every time I try to turn back

(Always wake up)

The singer can’t return to the image of leisure depicted in his dream. He must wake up to reality. But that does not stop him from dreaming, from trying to recapture some of the essence of that time long past when worries seem to disappear.

The mid-Twentieth Century still could provide adventure down a dirt road for a boy with a fishing pole. Often those times provided leisure, even when the fish were not biting. The calm of nature has a way of giving repose from life’s cares.

“You can’t have community at 70 mph” was one of my favorite quotes from my interview with Andrew Lytle. Interstate highways usually don’t have the character of an older road which leads by farms and small communities. He said rIding a horse puts you in the community, and lets you enjoy nature at a slower pace. You interact with people, and never know what may be around the next bend. By the same token, I think you can’t have leisure, speeding across a manmade lake in your bass boat with your 150 hp outboard at 50 mph. You may catch more fish with a weather app and fishfinder, but you may not find true leisure.

Mr. Lytle takes several pages of his essay to discuss the agrarian life. He recounts in detail the chores, the fireplace as the center of the house, the art of cooking, the harvest, preserving foods, crafts, music, dances, politics, Sacred Harp gatherings, barbecues, plays and dozens of other examples of the diversity, fullness and difficulties of making a living off the soil. The intricacies of social interactions such as the dances would surprise many today.

He then plows into the question of progress in bringing improved roads and transportation to the rural farmer. While there are benefits, there are also costs, including taxes for the government to grow and provide more. Those who really benefit are the construction, automobile and oil companies. A good road can be expensive, but a team and a wagon on a passable road can also get a crop to market at much less cost. While not all progress is negative, few stop to count the cost, especially if you are in government where counting is a lost art.

Though Mayberry doesn’t tackle agriculture directly, it is firmly placed in the agrarian tradition. Today factories not only produce products we use, but factory farms produce much of our food. Industrial farming looks at bushel per acre. Corporations look to wrest profits from the soil. Man looks to farm as a personal engagement with nature, working to derive sustenance from the land. The one is in harmony with nature, the other seeks to conquer nature, and that through brute force, mechanical contrivance and chemical alchemy.

The disharmony comes not from the use of more modern techniques, but in what is lost in the increase in scale and the loss of tradition. The farther we are from the dirt the easier it is to see what an equation of so many pounds and gallons gives in dollars, and the easier it is to lose sight of the necessity of having harmony with nature. Andrew Lytle famously said a farm is not a place to grow rich, it’s a place to grow corn. (his father’s plantation was named Cornsilk, and was flooded by the Tennessee Valley Authority in their program of dam building to tame the Tennessee River.)

Fortunately, small farms are making a comeback, specializing in quality meat and produce. The descriptions may be new, but the idea is not. Organic, grass fed, raw, unfiltered, heirloom, farm fresh, farm to table, farmers markets- LOCAL, not shipped hundreds or thousands of miles.

Though the Agrarians did not specifically dwell on food, the fact that industrialization has done so much harm (though their advertising agents and government stooges cover well for them) is a double insult to tradition. Our food comes from the same earth, yet while more abundant, it is less nutritious. Soils are depleted, and overplanted, sometimes 3 crops in one year. No wonder we are sick so often. What good are more bushels when the nutrition is so much lower.

While Mayberry does not address government as such, the work of progress is often defined by and brought about by elites, either in government or near to it. Progress has a way of making things always bigger, centralizing rather than localizing power. Whether called mercantilism, socialism, nazism or communism, the individual is sacrificed for the sake of the elite. Tracts Against Communism was one title suggested for the Agrarian’s manifesto before ITMS was settled on. Mayberry is certainly a call to reject this aspect of progress and embrace the local. Encouraging them to think local and act local would be superfluous for those front porch sitters.

Many country songs today take us back to those simpler times and traditional values. They sing of the common man working hard, raising a family and going to church. Entertainment is a community event-ballgames, dances and cookouts. You hear of small farms with the white farmhouse, planting rows of corn, the fishing hole, going to church, raising a family and following traditions. Sounds a little like the Agrarians. Perhaps we are turning back to basics-

Dirt

Dirt roads

Dirt on your truck

Dirt on your boots

It appears that the soil still calls out to some, calling them back to communion with nature. Back to their own Mayberry.

Our trip is lost, and now we search.

A spiritual trip by faith we comb.

Turning back over the course,

The road we want, is the one for home.

From “The Road Leads…” ( final stanza)

I couldn’t help but think of “Luckenbach, Texas” by Waylon Jennings featuring Willie Nelson. We need to cultivate a different mindset in our children.

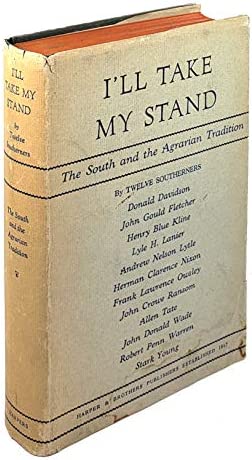

I recently purchased a copy of “I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition.” Thanks to the Abbeville Institute for introducing me to those Southern greats.