Neither side in the War for Southern Independence produced a finer or more morally upright man than Richard Montgomery Gano. He was the descendent of a distinguished military/evangelical family. His great-grandfather, John Allen Gano, was born in New Jersey and became a Baptist preacher. He joined the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, where he was known as “the fighting Chaplain,” and was famous for his bravery in battle. He frequently ignored enemy fire to minister to wounded soldiers. George Washington placed a particularly high value on him and chose Gano to officially declare the Revolutionary War over in a prayer. Gano probably baptized General Washington in the Potomac River, although this is a subject of dispute.

The first General Richard Montgomery Cano (1775-1815) was the grandfather of the future Confederate general. He moved the family to Kentucky and fought in the War of 1812, where he commanded a regiment. He was breveted brigadier general near the end of the conflict.

Richard Gano’s father was John Allen Gano (1805-1887). John’s parents died when he was young, and he was raised by an uncle, a tough veteran and a captain in the War of 1812. John became a lawyer, a lay preacher, studied under famous evangelist Barton W. Stone, and worked with Alexander Campbell. John became a leader in the Restoration Movement, immersed almost 10,000 people in baptism, and was instrumental in founding several congregations. He was noted for his powerful sermons and for raising thoroughbred horses. At his passing, one preacher said John did more to advance the Christian cause than any half-dozen ministers combined. He was also said to be an excellent father.

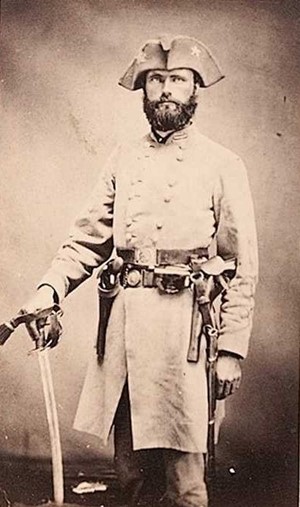

Richard Montgomery Gano was born in Bourbon County, Kentucky, on June 17, 1830, the grandson of the first General Richard M. Gano. The future Rebel general became a Church of Christ preacher noted for his kind, sauve, gentle and persuasive manner, and dynamic preaching. First, however, he enrolled in Bacon College (which later became the University of Kentucky) at the age of 12. He transferred to Bethany College, Virginia (later West Virginia) a year later and then the Louisville Medical Institute, from which he graduated in 1849.

Dr. Gano practiced medicine in Bourbon County, Kentucky, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana. In 1853, he married Martha “Mattie” Welch (1832-1895) of Crab Orchard, Kentucky, by whom he had a dozen children, nine of whom reached adulthood. He moved to Texas in 1859.

Gano settled in Grapevine Prairie, Texas, where he farmed, raised livestock, and practiced medicine. He was especially interested in bringing Kentucky racing horse breeds to Texas and later became one of the premier cattle breeders in the state. Comanches threatened his area (northeast Tarrant County) in 1859, so he organized posses from local citizens and smashed their raiding parties. For this, he was awarded a sword by the community. In 1860, they elected him to the legislature.

Richard Gano resigned his legislative seat in early 1861 and joined the Confederate Army. He raised a mounted rifle company, “the Grapevine Volunteers,” and was elected their captain. He soon expanded it into two companies. General Albert Sidney Johnston, a friend from Texas, requested Gano’s command (known as Gano’s Texas Cavalry Battalion) be transferred to his army for use as scouts. By the time it arrived in Mississippi, however, the Battle of Shiloh was over and Johnston was dead. Beauregard sent Gano’s command to Chattanooga, where it was assigned to John Hunt Morgan’s 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment, with Gano commanding Company G. In July 1862, he participated in Morgan’s first Kentucky raid and in August was involved in his Louisville & Nashville Railroad raid. He was promoted to major during this campaign (July 4, 1862), and he was given command of a squadron (his two Grapevine companies and a Tennessee company). Morgan, meanwhile, officially declared that he could not speak too highly of Richard Gano.

In September 1862, Gano’s squadron became the nucleus of the 7th Kentucky Cavalry Regiment. Gano was promoted to colonel (September 1) and participated in the Kentucky Campaign of 1862 as part of Kirby Smith’s command. He was part of Morgan’s Second Kentucky Raid (December 1862-January 1863). In February 1863, Richard Gano took charge of the 1st Brigade of Morgan’s Cavalry Division. He was diagnosed as having valvular heart disease in April 1863 and the physicians declared him unfit for military service. He continued to serve anyway. His brigade was left in the McMinnville, Tennessee, sector while Morgan galloped off on his disastrous Ohio Raid. General Morgan was captured and most of his command was destroyed.

After the Tullahoma campaign, Colonel Gano fell ill. He then returned to Texas with the remnants of his old Grapevine Volunteers (about 85 men). On September 1, Governor Lubbock gave Gano command of a 1,800-man cavalry brigade organizing at Bonham. He arrived on October 10 and was ordered to Arkansas on October 24. Here, he successfully raided and captured Waldron on December 27, 1863. He took part in defeating Steele’s Camden Expedition in 1864 but was severely wounded in the arm in a skirmish near Camden on April 14 and was temporarily replaced by Colonel Charles De Morse of the 29th Texas Cavalry. It has been written that he was involved in the Battle of Poison Springs, Arkansas, later that month, but he was not.

After he recovered, Gano led an unsuccessful foray against Fort Smith, Arkansas, in June 1864. His brigade was short of arms, clothing, and blankets and was thus plagued by desertions. It contained no more than 500 men by April 1864, but they were considered reliable. On July 27, Gano surprised the 6th Kansas Cavalry at Massard Prairie (near Fort Smith, on the border of the Indian Territory) and smashed it, killing, wounding, or capturing more than 150 of its 200 men. Gano lost seven killed and 26 wounded.

Encouraged by his victory, Gano pushed into Indian Territory, where he led the 5th Texas Cavalry Brigade and Stand Watie’s Indian Cavalry (consisting of Cherokees, Creeks, and Seminoles) in the Second Battle of Cabin Creek (September 19). Here, he and Watie overran the Union supply line, captured 130 wagons, 740 mules, and more than two million dollars worth of supplies. General Kirby Smith, the commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, called it “one of the most brilliant raids of the entire war.”

Stand Watie, the only Native American general on either side during the Civil War, was high in his praise for Gano writing in October 1864: “. . . the conduct of General Gano on all occasions being such as might be expected of so gallant an officer.”

Colonel Gano was give command of a brigade in Maxey’s Cavalry Division in September 1864 and led it until March 1865. Although he unofficially served as an acting brigadier general since early 1864, Richard Gano was not formally promoted until March 18, 1865, with a date of rank of March 17. Sent to Nacogdoches, Texas, he was recommended for promotion to major general, but the South surrendered before any action was taken. He later remarked that he fought in 72 engagements during the war and was successful in all but four. He had five horses shot out from under him during the conflict. Three of them were killed.

Richard M. Gano was one of those rare people who was successful at everything he attempted. He returned home and was ordained as a minister in the Disciples of Christ (aka Christian Church or Church of Christ) by his father in 1866. He helped establish several churches in northern Texas and Kentucky over the next 30 years. He continued to be fervently interested in stock breeding, importing important cattle, horse, sheep, and hog bloodlines into Texas. He and two of his sons formed the Estado Land and Cattle Company, a successful livestock and real estate firm, as well as the G4 Ranch (55,000 acres in the Big Bend country of Texas) and was on the Board of Directors of the Merchant and Planters National Bank in Dallas. He was a millionaire by the early 1880s. He was also active in the Prohibition movement and the United Confederate Veterans.

General Gano’s reputation as a Southern warrior commended itself to the citizentry. He held frequent gospel meetings which were always well attended, and it was said he personally baptized more than 10,000 people, although one source placed this number as low as 4,000—which is still tremendous. He became friends with David Lipscomb, another Church of Christ pioneer, despite the fact that Lipscomb did not believe Christians should fight for the kingdoms of the Earth. Once, Lipscomb bragged that he never smoked a cigar, chewed tobacco, or drank alcohol or coffee. Neither have I, Gano responded, adding that he never consumed a glass of tea. “I yielded the palm of praise to him,” Lipscomb concluded.

Richard Montgomery Gano was an elder at the Church of Christ in Dallas for some years. He had many great-grandchildren, the most famous of whom was legendary billionaire Howard Hughes (1905-1976). To celebrate his birth, General Gano took Hughes and his parents to dinner at the best steakhouse in Dallas. Hughes, however, did not live up to the morally upright legacy of his great-grandfather.

Richard Gano died of uremic poisoning in Dallas on March 27, 1913, at the age of 82. He is buried in Oakland Cemetery, Dallas. His old “dog-trot” cabin in Grapevine was moved to the Dallas Heritage Village, which is on Gano Street.

NOTES AND SOURCES: Gano’s appointment as brigadier general was confirmed by the Confederate Senate on March 18, 1865, which was also his date of rank.

William C. Davis and Julie Hoffman, ed.s, The Confederate Generals (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: 1991), Vol. II, pp. 154-155; Basil W. Duke, History of Morgan’s Cavalry, (Cincinnati, 1867), pp. 219, 234, 299, 386; John H. Eicher and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands (Stanford, California: 2001), pp. 247-48; Find-a-Grave Memorial, Richard Montgomery Gano and family members, accessed 2022; David Lipscomb, Gospel Adovocate, May 29, 1913, p. 514; Stewart Sifakis, Who Was Who in the Confederacy, Vol. II of Who Was Who in the Civil War (New York: 1988), p. 99; United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records, Series 1, Vol. XVI, Part 1, p. 881; Vol. XXXIV, Part 1, pp. 783, 846; Part 2, p. 1085; Part 3, p. 733; Vol. XLI, Part 1, p. 785; Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Gray (Baton Rouge, Louisiana: 1959), p. 96; Jack D. Welsh, Medical Histories of Confederate Generals (Kent, Ohio: 1995), p. 75.

outstanding

Very interesting article. Thanks for writing it. As a Bethany graduate it was especially nice to see the College mentioned, but the many connections of this family throughout history are well worth learning about.