This piece was originally published at SavannahNow.com

By H. Lee Cheek and Sean Busick

America’s Founders did not agree on much. They were not a monolithic group of men. Further, some of the things they did agree on make us uncomfortable today. Those who are in the habit of citing what “The Founders” thought as gospel would do well to keep this in mind.

Here is one thing most of the Founders did agree on: political partisanship is unhealthy and a danger to the country. They believed that republics were fragile and that civic virtue was necessary to prevent them from collapsing into anarchy or despotism.

Partisanship thrived where civic virtue was lacking. Whereas partisanship divides us and threatens effective governance, civic virtue unites us as citizens with a common interest.

According to a famous anecdote, upon encountering Ben Franklin in Philadelphia in 1787, a woman asked him what the delegates in the Constitutional Convention had been busy creating. “Have we got a republic or a monarchy?” she asked. Franklin replied, “A republic, if you can keep it.”

A threat from the nation’s beginning

The Constitution was designed to establish a republic which, like all republics, depended upon civic virtue in order to survive. Citizens and elected officials alike would have to behave responsibly; if we cared about our republic we would have to place the good of the country above selfish aggrandizement, above partisanship.

The degree to which we are disconnected from the Founders can easily be measured in our political partisanship. They, being human, often failed to live up to their own ideals.

Yes, they decried political parties, but they also split into Hamiltonians and Jeffersonians and founded our first political parties. However, they at least tried to temper their partisanship with civic-mindedness and were capable of feeling shame about their shortcomings.

Early American politicians seldom campaigned for themselves, leaving that bit of dirty work to their subordinates. For example, presidential aspirants confidentially sought out supporters to endorse their candidacy and write political biographies of themselves for public consumption.

Our politicians do not know how to stop campaigning and just might feel shame if it appeared they took a break from self-promotion and political warfare. Among the Founders it was an insult to be accused of partisanship or factionalism. We proudly announce our partisanship on our clothes, bumper stickers, and Facebook profiles.

In fact, some of our fellow citizens become so attached to a new, more dangerous partisanship that they are willing to attempt to disrupt our democratic way in pursuit of keeping their party in office.

Disagreement makes for good decisions

In terms of the “real world” of American politics, the Founders believed civic virtue in a republic also required deliberation and compromise.

These qualities allow leaders and citizens to listen to each others’ ideas. The Founders believed disagreement was not only good, but the interplay of ideas actually provided the basis for making the decisions that were in the best interest of the country.

Our Constitutional Convention and the state ratifying conventions that followed are the world’s best example of working through complicated issues, and compromising, in the pursuit of a higher purpose than self-interest.

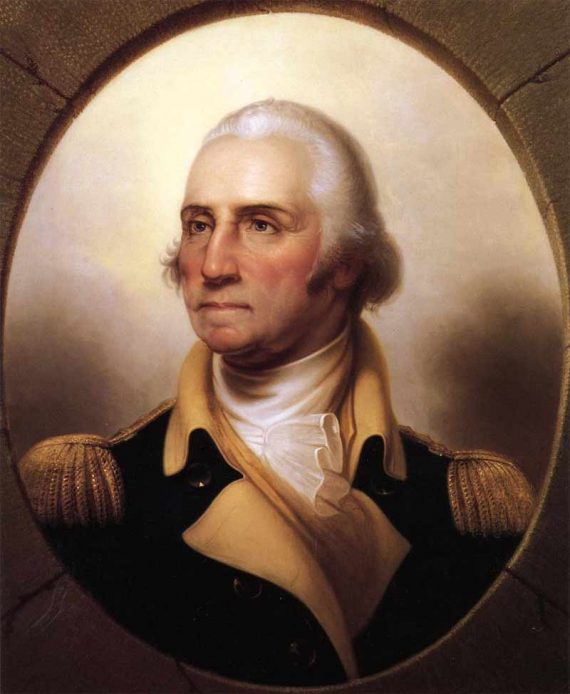

George Washington warned us against partisanship in his Farewell Address, which is read to the Senate every year on his birthday. “Let me now . . . warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the spirit of party generally,” he wrote.

Partisanship is the “worst enemy” of popular government. “It serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration,” Washington cautioned. “It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption.” If we want to keep our republic we need to guard against our partisan impulses.

Successful governance is serious work and often requires deliberation and compromise for the common good. It is not a sport, there should not be teams. Our fellow citizens are not our enemies, nor should they be. When politics becomes a game of winners and losers we all are the losers.

Note: The views expressed on abbevilleinstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.

wasnt it partisanship that led to the group in England that eventually ended up making the Declaration? lockean stuff, etc? it seems hard to belives that Washington would have said this knowing his own lot as a Virginian.

Who is president, shouldn’t really matter.

Maybe I didn’t see in the constitution the unlimited powers granted to a pres during “time of war”.

I did see though, where congress has to vote on declaring war.

But, unfortunately, that’s all history now