Lynchburg, Virginia, today displays many markers of its Civil War history. There are several signs in and around the city that indicate where Confederate forces were placed in defense of the city. There is a statue of a Confederate infantryman at the top of Monument Terrace. In Riverside Park, what is left of the hull of Marshall, which carried the body of dead Gen. Stonewall Jackson through Lynchburg, sits in an enclosed display near James River. At the junction where Fort Avenue splits, just beyond Vermont Avenue, and Memorial Avenue begins, there is a monument to Jubal Early. There too sit Fort Early just to the west of that juncture and Fort McCausland on what is today Langhorne Road, each having served as part of the outer defenses of Lynchburg, and each general considered a Confederate hero of the battle. Finally, Samuel Hutter’s Sandusky residence, the headquarters of the Union’s leaders during the campaign, sits undisturbed down Sandusky Drive to the north of Fort Avenue.

Why does Lynchburg display so many markers, ultimately in the cause of a losing effort?

It was one of the most important Southern cities in the conduct of the war—it was an industrial city in the manner of a Northern city—and was the only major Virginian city not to be captured by the North. By analysis of how the city was not captured, we gain an additional perspective on the military history of the Civil War and see in this instance the large consequences of following one’s inclinations instead of one’s orders.

Lynchburg, Virginia, was deemed by both North and South to be a pivotal city in the conduct of the Civil War. It was centrally located in Virginia, where much of the fighting was conducted. Furthermore, it was, with its three railroads and the Kanawha Canal, an extraordinary transportational hub. Confederate troops would gather in Lynchburg to be sent via railroad to other places, and it was a strategic hub for supplies, and even, with its numerous warehouses, and a place to bring wounded soldiers from the South with the hopes of convalescence. Moreover, it was also near Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy. Yet with a wall of mountains to its northwest and the James River to the east, it was defensible.

Despite its significance, it was not until the summer of 1864 that the Civil War came to Lynchburg. Union Gen. David Hunter was tasked with capturing Lynchburg. Hunter had a history of conducting military affairs as he saw fit to do so, not as he was ordered to do. For instance, in 1862, he issued, without proper authority, an order to free all slaves in Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina. That order was quickly countermanded by President Lincoln. He also, and without authorization, began enlisting black soldiers from South Carolina to form 1st South Carolina. Lincoln again rescinded that order.

In June 1864, Hunter and his men approached Lynchburg after leaving the Shenandoah Valley. The Confederate convalescents from the hospitals, under the command of invalid Gen. John C. Breckinridge, erected breastworks around the city in some effort to defend it and its citizens.

Hunter was under orders to destroy the railroad and the Kanawha Canal at Lynchburg and generally to follow a scorched-earth policy vis-à-vis all industries that might be used to benefit the South on his way through Staunton to Lynchburg. Union Gen. Ulysses Grant wrote to Hunter: “The complete destruction of [the railroad] and of the canal on the James River are of great importance to us. You [are] to proceed to Lynchburg and commence there. It would be of great value to us to get possession of Lynchburg for a single day.” Why did Grant add the qualification “in a single day”? Lynchburg’s infrastructure could be annihilated in one day, thereby crippling the South’s capacity to transport goods, soldiers, and the ill and wounded.

Yet again Hunter did as he pleased, not as he was commanded to do. As he moved southwest from Staunton, he tarried so that he could burn or destroy almost everything on his path to Lynchburg. He was sidetracked by several raids in Lexington where he remained from June 11 to June 14. He burned down the Virginia Military Institute and plundered Washington College—he even took a statue of Washington as part of this booty—and had plans to raze even more as he traveled—for instance, the University of Virginia. Yet those raids were his undoing in the battle, as they much slowed his advance on Lynchburg. Darrell Laurant writes in “The Battle of Lynchburg”: “The invaders were thwarted for a number of reasons, but chief among them, there was the failure of commanding general Hunter to cut this vital rail line north of the city when he had the opportunity.”

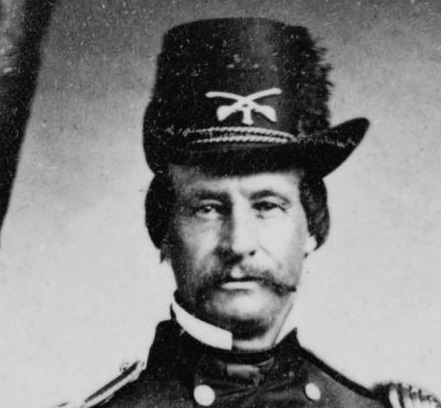

Lynchburg, before the arrival of Confederate troops, was protected only by some 700 convalescent soldiers, under active command of the lame Gen. Francis Nichols. Knowing of the city’s vulernability, General Robert E. Lee ordered Gen. Jubal Early to assist the invalids Breckinridge and Nichols to defend Lynchburg. Breckinridge had Gen. D.H. Hill set up breastworks around the city. They too were aided by Gen. John McCausland, who arrived in Lynchburg ahead of Hunter, and by Gen. John Imboden, who had a small remnant of cavalry, and the two had established a defensive posture to the southwest of Lynchburg, at a breastwork near the Quaker Meeting House, near Salem Turnpike.

Early and the 2nd Corps arrived in Lynchburg early in the afternoon on Friday, June 17. With the railroad tracks maimed in several places, transit from Charlottesville to Lynchburg took five hours. Until Early arrived, McCausland and Imboden had kept Hunter’s troops, over 10 times the Southern number, in check, but were slowly being driven back. Even with Early’s troops, the Confederates were still at a distinct numerical disadvantage—some 8,000 to 10,000 Confederate soldiers to some 16,000 to 18,000 Union soldiers—so Early ran trains all night along the tracks near James River on June 17 in an effort to convince the Union troops that still more Confederates were arriving. Hunter wrote in his diary, “During the night the trains on the different railroads were heard running without intermission, while repeated cheers and the beating of drums indicated the arrival of large bodies of troops in the town.”

Early’s ruse—to pretend that there were more Confederate soldiers than there were—worked. Hunter was convinced that he was fronted by superior numbers. Ammunition, he wrote in his diary, was also running short. After discussion of military affairs with colleagues from Sandusky, Hunter ordered an immediate withdrawal of Union troops on the night of June 18. Hunter later wrote Gen. Grant of his decision, “It had now become sufficiently evident that the enemy concentrated a force at least double the numerical strength of mine, and what added to the gravity of the situation was the fact that my troops had scarcely enough of ammunition left to sustain another well-contested battle.”

Early, the following morning, attempted to retrace the retreat of Union soldiers, and did so with some success, as he soon caught the rear guard of the retreating blue-coats and killed a number of them. Yet the Union soldiers did escape to Salem and eventually to the mountains of what is now West Virginia. Grant however had requested that Hunter, if in retreat, go toward Washington, where his troops could be of use in defense of the city. He chose a safer route, because, he said, of his dearth of ammunition.

Confederate Capt. Charles Blackford, who left behind a lengthy account of the battle that was published in 1901, challenged Hunter’s account of having inferior numbers and of being low on ammunition. Hunter knew that his numbers were superior—“he had scouts on both railroads and the country was filled with the vigilant spies who prided themselves on their cleverness”—and he was not low on ammunition. “It cannot be believed that a corps was short of ammunition which had been organized but a few weeks, a part only of which had been engaged at Piedmont, and which had fought no serious pitched battle, and the sheep, chickens, hogs and cattle they wantonly shot on their march could not have exhausted their supply. The corps would not have started had the ammunition been so scarce.” The Union, he maintained, was well-stocked with ammunition. He concluded that Hunter, more interested in campaigns where there was little chance of loss of life, was a coward.

There is meat in Blackford’s assertions. Hunter could readily have arrived in Lynchburg by June 16, when he would have faced only the convalescent guard, the Silver Grays, and the few other men available to Gen. Breckinridge. Had he done so, Lynchburg would have fallen. Yet he tarried in Lexington to pillage and burn needlessly. He was also slowed by the constant burning and plundering of houses along the way which caused pain and loss to Southerners uninvolved in the fight and nowise advanced the North’s cause.

Thus, one of the most significant cities for the fate of the South, Lynchburg, was not captured. Had Hunter arrived before Early and had he destroyed the railroad tracks and Kanawha Canal as he was ordered to do, the city would have fallen and the Civil War would likely have ended in 1864.

And so, the real savior of Lynchburg was neither Early nor McCausland, but the Norther general David Hunter, about whom, scholars agree, had ambitions much larger than his abilities.

“…had ambitions much larger than his abilities.”

And today, this character flaw is like a blanket spread over the political world from sea to shining sea.

Great, Mark! Thanks! A seldom covered chapter with detail that I didn’t know.

It’s always good reading of the “Bad Old Man” Jubal Early and John McCausland, two fierce and dependable Confederate field commanders. McCausland especially has been under-appreciated having been often away from the primary theatre of war. A true “Unreconstructed Rebel” he finished the War with a bounty on his head for the burning of Chambersburg, under orders from Early and in retribution for Hunter’s action in the Shenandoah Valley. McCausland remained under warrant for arrest in Pennsylvania for years following the War until U.S. Grant ordered that he had been paroled, therefore being free from prosecution. It is believable that McCausland said, as is claimed, when he heard of the assassination of Pres. McKinley, “I am glad of it! He was one of Hunter’s staff!”

A postscript: Hunter wrote Gen. Lee after the War, apparently seeking validation for his retreat westward through the mountains. Lee responded, “I certainly expected you to retreat by way of the Shenandoah Valley, and was gratified at the time that you preferred the route… to the Ohio – leaving the Valley open for Gen. Early’s advance into Maryland”. Ouch.

Thank you for more info. The postscript is spot on.

Hunter was a Virginian, not a Northerner. He was one of a few Southerners who fought for Lincoln’s “Union,” but unlike Thomas, he had almost less military ability than character ~ and that was hard under the circumstances. You will notice that all Southerners who fought for the North were treated with disdain and often their talents were ignored and their abilities defamed. Frankly, I consider that only proper under the circumstances!

Thanks for clarifying….

A Virginian? Hunter was born in Troy, New York…