The best of the many Confederate memoirs, in my opinion, are those of General Richard Taylor (Destruction and Reconstruction) and Admiral Raphael Semmes (Memoirs of Service Afloat and Ashore). There are also many excellent women’s diaries and memoirs, perhaps a subject for another occasion. Taylor and Semmes were men in high places, intelligent and experienced, keen judges of character, and capable of philosophical reflection about the destruction of the South and the Constitutional Union that they had resisted.

Henry Kyd Douglas in his memoir, I Rode With Stonewall, was also intelligent and literate but a younger man in the midst of battle. He finished the memoir about 1899, using his diaries, letters, and recollections. The book did not appear until 1940 when a relative took it to the University of North Carolina Press. The publisher provided the catchy title although it is in keeping with Douglas’s fresh and lively style.

Douglas was raised on the Maryland bank of the Potomac, in easy sight and communication with Virginia and not far from the soon to be famous Harpers Ferry. When The War was imminent he was a 23-year-old lawyer in St. Louis. He went home and enlisted in a Virginia unit. Douglas was soon invited to join the staff of Jackson, then at the very beginning of his successes and rise to fame. Douglas served Jackson through all his campaigns in the great battles from the Valley Campaign to Chancellorsville.

To be on Jackson’s small staff was not a position of glamour and glory. It took courage, judgment and energy and was exhaustive to man and horse: carrying orders and messages from the commander across battlefields, making observations under fire of terrain and enemy troops, directing emergency movements.

Douglas got to know Jackson well. He saw him every day, rode with him, ate with him, and often slept nearby. He presents as clear an understanding as we are likely to ever get of Stonewall the soldier and Thomas Jackson the man.

Douglas’s position acquainted him with many important commanders—Jeb Stuart, Early, Ewell, A.P. Hill and many others—carrying orders and attending many councils in the field. His experience gave him considerable insight into the merit or lack of merit in military decisions and the personalities of important generals.

Douglas tells a touching story about the night before the first attack at Chancellorsville. Jackson and staff were living on the ground in the Wilderness. The general placed his cloak over a sleeping young soldier. Douglas believed that Jackson that night caught the pneumonia (not wounds) that killed him a few days later.

Union generals never slept in the rough. They seized the best civilian house nearby, moved in their elaborate staffs and escorts, and enjoyed comfort and fine dining. But the celebrity pseudo-historian V.D. Hanson tells us that the Union army was free, open, and democratic and rank hardly mattered, while Confederates leaders operated with aristocratic pretensions. Union generals often issued boastful reports claiming their defeats as victories. Jackson told the South not to thank him for his victories but to thank God.

After Jackson’s death Douglas served on the staffs of other generals. He was wounded and captured at Gettysburg and imprisoned for a year, although one of the last lucky Confederates to be exchanged. He returned to the Army of Northern Virginia and at Appomattox was in command of the remnants of a Virginia brigade. Meanwhile, his family’s home had been ransacked and his father taken off to prison.

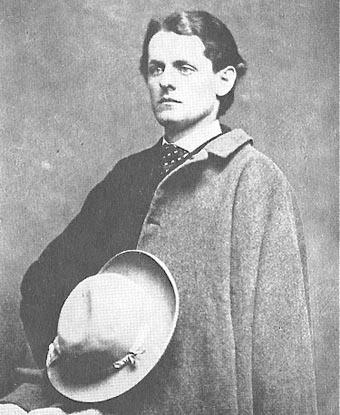

After the war, living at his family home near Shepherdstown, (West) Virginia, as a paroled prisoner, Douglas was persuaded by a young lady to go into town and have his photo taken in uniform. For this act, Douglas was arrested for treason and snatched away to the Old Capitol prison in Washington, with attempts to implicate him in the Lincoln assassination. It happened that he was there at the same time as the Lincoln assassination conspirators and was privy to much information about the “trial” by the illegal military commission that murdered the innocent Mary Surratt. Douglas was subjected to a kangaroo trial by the same commission but released. But he was re-arrested, “almost every week,” as he says, until finally “pardoned” on grounds that his term had expired, though he was amused that he had never actually been convicted or sentenced or asked for a pardon.

After the war, Douglas settled in Hagerstown, Maryland, and became a prominent citizen of that state—a successful lawyer, candidate for Congress, and adjutant general of the state militia. He was offered a brigadier’s commission in the Spanish American War. He declined and passed away in 1903.

I Rode With Stonewall is a great read and of real interest to any one who wants the truth about the great war of the 1860s.

One of my favourite books about The War. It acquaints us with the real General Jackson. His portrait sits high up on top of a tall hutch in my living room. I also remember making a visit to Guinea Station where Stonewall died, his last words, “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.” I made my grandbabies memorize this and they had to recite it in order to drink out of one of my Stonewall coffee mugs. Many thanks to Dr. Wilson for writing this wonderful essay.

Your story is deeply touching. Thanks for sharing it.

Thank yo, Sir.

Thank you, Dr. Wilson, for a good, quick summary of this book. I’ll have to buy it and put in my library!

Stonewall Jackson is everyone’s idea of a wartime hero, like Field Marshall Ewrin Rommel is for the British.

?

I’ve always thought that the probability of the South’s prevailing in their war for independence would have been greatly enhanced had Jackson lived. So grateful for the publication of this excellent book.

–Donald S. Whiteheart, Sr.

Stonewall taught his slaves to read. Lincoln and Grant did not. Stonewall repulsed a Mexican assault on his position with only one cannon and a handful of soldiers. Stonewall was a military genius, being derided by his own troops as “wagon collector”. Stonewall knew only logistics wins wars. Stonewall taught physics at VMI…called natural science then.

“When I was a kid, Uncle Remus would put me to bed…with a picture of Stonewall Jackson above my head.”

Rest in Peace, General Jackson.

“Jackson told the South not to thank him for his victories but to thank God.“

Thank you Dr Wilson for this little book review and reflection on General Jackson. It struck me recently and I was reminded again reading the quote above that even after WWII there were not that many generals in the American Army and very, very few four stars. Today I believe there are 44 or 45 four star generals and most of them I can imagine are probably” thanking themselves and signaling others to thank them for their service. “

Totally different types and spirits today from General Jackson who actually served a cause and a people until the end.

Years ago I visited the little house and memorial outside Fredericksburg where General Jackson spent his last hours. I sometimes wonder if it’s still there or if the contemporary American maoists have canceled it in their ignorance of what the“four olds” actually are.

Any how thank you for placing another little gem in the garbage dump “for heaven and the future’s sake.”