In the middle of July, 1864, Chickamauga, Missionary Ridge, and Kennesaw Mountain had been fought and Sherman was at the gates of Atlanta. In Virginia, Grant had fought Lee for two months and had lost as many men as Lee had in his entire army at the beginning of the campaign, and was now investing Petersburg. Jubal Early’s Second Corps had raided Washington and had come within a day of entering it with his troops. The butcher’s bill was so high that Abraham Lincoln was calling – without any success – for another half million volunteers to subjugate the South. At this point, many were the calls in the North for a cessation of hostilities and a negotiated settlement to the war.

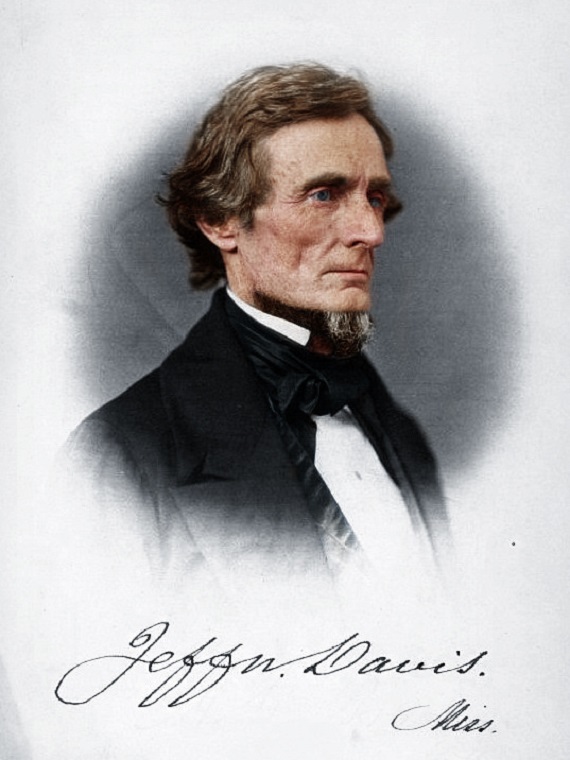

Colonel James F. Jaquess, a Methodist minister and the colonel of a regiment of Illinois volunteers, and J. R. Gilmore, a New York businessman with connections in Washington, secured for themselves, from Lincoln, an unofficial visit to Richmond under a flag of truce to meet with Jefferson Davis. Outside of “Beast” Butler’s lines at Bermuda Hundred, they were met by Judge Robert Ould, Confederate Commissioner for Prisoner Exchange, and escorted to Richmond where they were lodged in the Spotswood Hotel. The next morning Judah P. Benjamin, Secretary of State, arranged for their meeting, in his office, with President Davis. Davis greeted them cordially, shaking their hands and telling them he was glad to see them, and welcomed them to Richmond.

Jaquess opened the interview by expressing the hope that Davis, wishing peace as much as these two gentlemen did, might suggest some way to stop the effusion of blood.

Davis replied: “In a very simple way. Withdraw your armies from our territory, and peace will come of itself.”

Jaquess then suggested that Lincoln’s recent Proclamation of Amnesty might be a basis for negotiations.

Davis cut him short. “Amnesty, Sir, applies to criminals. We have committed no crime.”

Then Gilmore suggested that the two sides lay down their arms and let the matter be settled by a referendum, which would mean that the twenty million at the North would have more than double the majority over the South.

Davis replied: “That the MAJORITY shall decide it, you mean. We seceded to rid ourselves of the rule of the majority, and this would subject us to it again.”

Gilmore saw that the issue boiled down to “Union or Disunion,” although President Davis preferred to term it “Independence or Subjugation.” Gilmore then appealed on personal grounds and asked if Davis, as a Christian, leave untried any means that might bring peace.

“No, I cannot,” Davis replied. “I desire peace as much as you do; I deplore bloodshed as much as you do. I tried in all my power to avert this war. I saw it coming, and for twelve years I worked night and day to prevent it, but I could not. And now it must go on till the last man of this generation falls in his tracks, and his children seize his musket and fight his battle, UNLESS YOU ACKNOWLEDGE OUR RIGHT TO SELF-GOVERNMENT… We are fighting for independence – and that, or extermination, we will have.”

Additional matters were discussed, such as the military situation, which Davis considered favorable to the South, and slavery, which Davis never considered to be “an essential element” in the contest, but “only a means of bringing other conflicting elements to an earlier culmination.”

It all came down to one thing. As President Davis rose to lead the two gentlemen to the door, he shook their hands again and told them at their departure:

“Say to Mr. Lincoln, from me, that I shall at any time be pleased to receive proposals for peace on the basis of our Independence. It will be useless to approach me with any other.”

There is a great deal about Davis to admire. But when he said, “We are fighting for independence — and that or extermination, we will have,” I’m not sure that fighting to the last drop of blood, in a war that almost certainly was unwinnable, is really an admirable thing.

Live free or die…

Does that slogan really answer the responsibilities of a head of government responsible for nine million people? It doesn’t seem to me to be a simple question.

You are placing President Davis on the horns of a moral dilemma…General Lee disobeyed President Davis by surrendering “his” Army… it wasn’t Lee’s to surrender. Lee was presented with an honorable end to the war…later, Lee realized his mistake as the 14th Amendment disenfranchised White Southern Males in perpetuity…perhaps later to be Amended to include their children…and their children’s children…

Men must at times stand alone…we have seen recently in a gentle reminder during the covidscam how mobs can turn ugly, quickly. Good leadership is hard to come by when men are compromised.

President Davis and his cabinet were captured while re-locating the government of the CSA. But he had no “where” to go…perhaps he thought a country which would burn entire cities to the ground and starve civilians on purpose would terminate his life without so much as a trial. If so, his decisions were personal and perhaps flawed by self-preservation instinct. If he knew as we all do now, the South would be subjugated, White Southern Males would lose their rights as citizens in conquered territories, it was right for him to continue to fight and Lee was wrong.

You’re jumping to conclusions about what I am saying about Davis. All I am really saying here is that no statesman should ever talk about the extermination of his people in any context. Period. I certainly do not underestimate the difficulties of the position he was in.

I cannot fault the commanders who surrendered their forces, hoping for the best. The positions were similarly difficult. I think Forrest said it best, “…. any further resistance on our part would be justly regarded the height of rashness and folly.”

Albert…the union army committed war crimes on a scale never seen in a western army. We are lucky they needed us to manage their new field hands or they would have killed us all, as they exterminated Indian tribes who resisted…the 5 Civilized Tribes thought they’d get a better hand dealt from the Confederacy…these men weren’t stupid…many of their leaders had been taken north to see the immense cities…and they were impressed…but they were still moral men trapped in a world that was becoming immoral…the yankees were immoral…they lied then and they continue to lie today without cease…although it is much more difficult for them to maintain control of the narrative due to boards such as this one…and for that we can all rejoice.

After three years of bloody war, why would the Yankees be more ‘lenient’ to the South if it surrendered in 1864 rather than when it did? There was still some hope for the South and President Davis knew he was facing the extinction of his country whenever he would surrender to an implacable foe.

President Zelensky would understand President Davis’ reply very well.

All true. But were there no alternatives between surrender and extermination?

Lincoln would not accept Southern independence. Any negotiation by Davis with the Lincoln government would have to involve the *surrender* of Southern independence. So, no, there was no option available between the extremes.

A little dissimulation might have been better than a blanket no. Perhaps it would have been helpful to let Lincoln bear the onus, more publicly, of letting the war continue.

Ads I said above, a statesman should never talk about the extermination of his people.

Dear Mister Traywick,

Another one of your hugely instructive stories. But if I pass the story on, inevitably, someone will ask where I got the (to them, unimaginable) story. To deny them the comforting feeling that this must be some latter-day ‘fake news, please always try to give us a source for your stories. That helps to make them incontrovertible (And will shock the hell out of them!)

J.R. Gilmore published his visit to Richmond. “We must conquer”

Thank you, Mr. Traywick.

Whether we die at, say, age 20 or age 90, the difference as a sliver of eternity, is immeasurable and insignificant.

And I believe that if my Lord and Savior will grant it, I will live eternally, beyond the clutches of Satan.

Jefferson Davis and most Southerners of that time believed similarly.

(As an aside: Make no mistake – Christian civilization is their ultimate target, and what makes them fear and hate our “Bible Belt” culture.)

So if the question of living or dying rests upon the choice of living subjugated, in the fetal position, begging for life, or dying face toward the enemy, while reaching for his throat, I choose the latter.

And frankly, I can not see a greater merit in Mr. Alioto’s inferred position.

Mr. Traywick sees the lasting conflict with uncommon clarity.

You are, of course free to infer whatever you choose. My position is that Davis’ actions and choices, like that of all historical figures, are validly open to question. As I put it in another post, I would question whether the drastic extremes were the only alternatives. For that matter, is it not a failure of statesmanship if a people are reduced to a situation in which the only choices are the ones you described?

“The mark of the immature man is that he wants to die nobly for a cause, while the mark of the mature man is that he wants to live humbly for one.” Wilhelm Stekel. I don’t think that is an answer to all the questions one might ask about Davis, but it is a fair point to bring into any consideration. (With the caveat that what Davis was discussing was not his own death, but the fate of nine million people.)

why is it always the choices of the south that are in question? Why is the question not why is Lincoln held to such high regard for starting a war to battle american against american at the cost of 700k+ lives?

Mr. Alioto, with the privilege of hindsight anyone can second guess a leaders” decisions. If the North had withdrawn, the inevitable peace and ally of two common peoples would be much better than the current Federal government leviathan.

I absolutely agree with you about what would have resulted from a cessation of the Northern invasion.

Isn’t what you refer to as “the privilege of hindsight,” simply the study of history? Why, after all, would anyone read this website?

So long as we don’t pass judgement, history can teach us much…study the facts, not the opinions.

It is a fact, no northern State ever passed a tax to purchase slaves from their masters…it is a fact, every stripe on the US flag represents a slave State. Northern States merely allowed owners, black, White and “native” American to sell their stock down the river.

The north holds no high ground…the northern States and federal government refused to abide by Dred Scott…slavery was not the cause of the war…refusal to uphold the Constitution of these united States was the cause of the war.

I agree with everything you say in your second and third paragraphs.

Judgment-free history is, I think, probably too much to ask. There will always be some degree of making judgments about the history we consider. It is probably not the least of the Lord’s mercies that the individuals involved are beyond any consequences from the judgments we may pass in trying to decide who we believe to have been right and who wrong.

Perhaps an example will clarify what I mean. After Lee’s surrender, Davis wanted to fight on. Almost no southerners went along with that. (Wheeler and Hampton were willing to be exceptions.) The southern people chose not to be exterminated. I think that was a good thing, and I believe it to have been true in Davis’ case as well. the last twenty years of his life were a meaningful contribution to the country for which all Americans should be grateful. Whatever of the South was worth fighting for in the 1860s that endures today in spite of all the attacks of the American Taliban, exists because the survivors of the war lived on, made the best of their lives and, to borrow a phrase from other circumstances in another century, endured the unendurable. I am grateful that they did.

Philosophically and metaphorically speaking, whoever Wilhelm Stekel is, he can kiss my grits. But not in my foxhole – I wouldn’t want him there.

Every man has his price, the highest price (death) may be judged as too high by many or most, but it is often the noble antithesis of “immaturity”.

Let Stekel or his adherents pronounce his oh so facile and “mature” creed publicly, say, on Memorial Day at any cemetery where the gallant dead rest and the humbly grateful living come to grieve and remember.

Neither is placing one’s life above that which is greater than life, “maturity.” Rather, it is merely base instinct, which even the lowest life forms possess, tho the clever, perhaps self serving Stekels of this world may try to dress it up.

Our country’s zenith, whether a memory or yet to come, is forever supported by the ultimate, heroic sacrifices of our forebears, who willingly chose death over subservience. And we are grateful that when their fearful test came, they had the enormous fortitude to overcome the gripping survival instinct and lay down their lives for posterity. That is, for us.

In the case of our Confederate forebears, the sacrifice is no less noble because it was not attended by the final military and political victory they sought. It seems doubtful in hindsight as it was obvious then, that continuing the fight would have produced victory. Surrender was indeed, the only rational option.

We can not fault the leaders for coming to that conclusion. And we should not fault any who came to it later than others.

But that reasoned conclusion did arrive to individuals at different times. To some, it was apparent as early as upon the twin mortal wounds at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. To others, it was not accepted until months after Appomattox and Bennett’s Farm. To some, not even then.

And we must understand that the Confederate leaders, who chose surrender, understood that in so doing, they might well be surrendering themselves ultimately to be hanged to death on false charges of treason. In other words, surrender might well mean death. Was that awful choice, which risked their very lives so that peace and reason might reign, “immature”?

In fact, that very real question hung over the heads of the CSA leaders like Damocles sword, and was not settled until Christmas Day, 1867, when Chief Justice Chase and Justice Underwood formally dismissed the indictments against President Davis.

I very much enjoyed reading this and the comments – opinion points well-presented and some angles that I have not given proper consideration.

A job well done on the discussion, gents. This is why I love reading Abbeville.