From the 2004 Abbeville Institute Summer School

It’s a privilege for me to be here. I’ve enjoyed the sessions very much so far. In fact, after the sessions yesterday I had to go and rewrite my conclusion just from things that I learned, especially about locality, localism, and patrimony. Just fascinating. Today I want to talk about James Henley Thornwell, Robert Lewis Dabney, and the shaping of Southern theology. There’s a lot of people that you could talk about if you wanted to discuss the shaping of Southern theology, like Broadus, Boyce, and others, great Southern theologians and exegetes of Scripture who should command more of our attention. But the two best individuals to start with are James Henley Thornwell and Robert Lewis Dabney, simply because I think they really are fantastic. If you look at the quality of their work, the quality of their writing, the depth of their insights, it’s just phenomenal. I did a Master of Arts in Church History before going to the University of South Carolina where I was required to do a lot of reading of American theologians, and I don’t think I was ever asked to read Thornwell or Dabney. It wasn’t until later when I really started reading and looking and seeing who these men were that I realized how much I had missed from their writings. Let me give you two quick bios of these two men and then we’ll start on the analysis that I want to give.

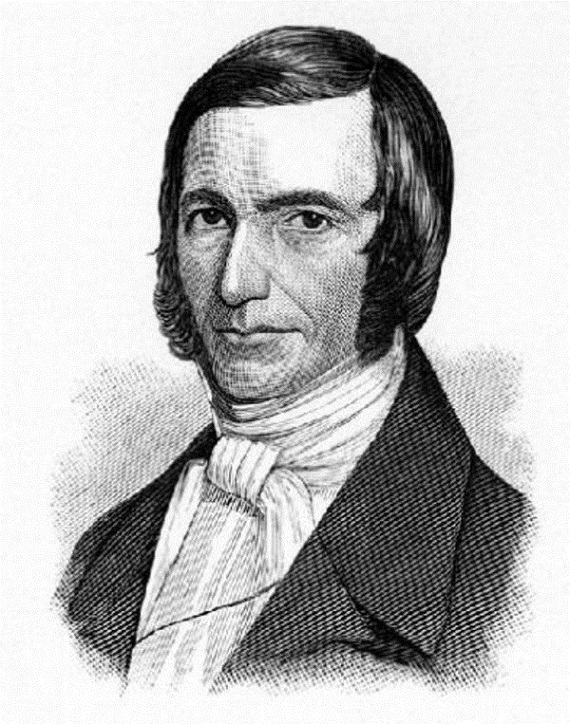

James Henley Thornwell was born in 1812 in South Carolina. Born into a Baptist home, he ended up being a Presbyterian. His father died when Thornwell was eight years old. He went to South Carolina College. It’s said that when he was at South Carolina College, he studied fourteen hours a day and then on Saturday read history for leisure. He was converted in 1832, decided to go into the ministry, and went to Andover Seminary in Massachusetts, but didn’t stay there long. He left because, he said: “They were awfully new-school.” Then he said: “The habits of the people there are disagreeable.” And then he said, really, one of the main reasons he left was because they did not offer German, Syriac, Chaldean, and Arabic, which he wanted to study. So, he transferred to Harvard, but he didn’t stay very long. He left Harvard, he said, because of the weather, but I think it was more because all the students that he met there were Unitarians. So, he went back home and studied at Columbia Theological Seminary, became a distinguished minister and scholar, and his work really became recognized in a big way. Some very distinguished people recognized his genius, George Bancroft among them. George Bancroft said that Thornwell was “the most learned of the learned.” He was called (and this is probably the best compliment he could have received) “the Calhoun of the church,” and he really was. When you look at Calhoun and see the almost prophetic way he understood how things were happening, and you read Thornwell, you’re reminded of Calhoun, I think, in some ways. He became a professor at South Carolina, eventually became the President of South Carolina College, and then went on to be a professor in the seminary there, Columbia Seminary. Thornwell died at the age of fifty. I can only imagine how much work he would have produced if he had lived longer. If you want to start with Thornwell’s works, Banner of Truth Trust has published the Collected Works of Thornwell.[1] Included in that is Benjamin Palmer’s biography of Thornwell, and I highly recommend that collection to you.

Robert Lewis Dabney was born eight years after Thornwell was born. He was born 1820 in Louisa County, Virginia. He was taught by his older brother and a local Presbyterian minister there in Farmville, Virginia. His father died when Dabney was thirteen years old, so both of these men grew up without a father. He went to Hampden-Sydney where he converted to Christianity at the age of seventeen. Off-and-on during his education, he would have to stop, go home, and work the fields just to keep his family going financially. He worked in the tobacco fields and the grain fields. He quarried stone. He rebuilt the family mill and founded a school. All of that at the age of eighteen. He took a master’s degree at UVA with a concentration in Greek, Latin, French, and Italian. Dabney later studied at Union Seminary, eventually spent most of his life teaching at Union Seminary, and established himself as an exceptional teacher and scholar. He was invited to be a Professor of Theology at Princeton in 1860. Charles Hodge, the famous theologian, practically begged Dabney to come to Princeton, but Dabney simply said he wanted to stay home. One of his reasons for refusing was a desire to remain with his slaves. He was afraid that if he left his slaves, if he sold them, the families would be broken up and he didn’t want to be responsible for that. So, he felt a real responsibility for them. Of course, in 1862, he became Stonewall Jackson’s chief-of-staff. Dabney was a renaissance man. Thomas Cary Johnson said this about him: “He was a good, practical farmer, a good teacher, a good pastor, a capital member of a military staff, a skilled mechanic and furniture maker. He bound books well and drew maps and plans for buildings.” A. A. Hodge, Charles Hodge’s son, said that Dabney was “the best theology teacher in America.” William Greenough Thayer Shedd, who is considered one of the great theologians in America, said Dabney was “the greatest living theologian.” These were not empty words. When you read the depth of Dabney’s writings, you understand what they’re talking about. He wrote a massive systematic theology, doing most of his writing during the Reconstruction period.

Most people think of Dabney as this crank during Reconstruction, upset over the loss of the War and so forth. In fact, he was a very productive scholar during the Reconstruction period and after. If you really want to start with some enjoyable readings of Dabney, I would suggest going to the five-volume set called Discussions. There’s Discussions, Theological and Evangelical (Vol. I), Discussions, Evangelical (Vol. II), Discussions, Philosophical (Vol. III), Discussions, Secular (Vol. IV), and then there’s a miscellaneous volume, (Vol. V), in which he writes on all sorts of things – economics, education, psychology. The depth and breadth of his thinking, even beyond theology, was astounding. He also wrote several books all the way up until he died. These include his systematic theology, a work on psychology, emotion, and so forth, and the earliest biography of Stonewall Jackson.[2]

Now, let me get to the topic about the shaping of Southern theology. In Richard Weaver’s excellent article, “The Older Religiousness in the South,” Weaver shows that in the antebellum South, religion had at least three compelling characteristics.[3] One, it was revealed, that is based on a settled revelation, thus not based on or subject to negation. Weaver said the second characteristic of Southern religion was its reality or realism. It was about reality. It was not compartmentalized, but was inclusive of faith, emotion, and nature. Third, it was a reserved religion. That is, it understood Southern religion did its role, which was religion and not politics. It was laissez-faire, thus not given to forced compliance or centralization. In a word, Southern religion was “anti-modern” in the best sense of the term. It was antithetical to the train of so-called “progress.” Conversely, in the North, especially New England, religion had, I would say, digressed into progression. By the 19th century much of Northern religion went headlong into ultimate negation and was therefore antithetical to reality. As a result, because New England lacked appreciation for simple assent (which requires humility), and for creation and nature, it had a vociferous appetite to dominate everything, whereas the South was the land of faith, New England, as Weaver wrote, was “the land of notions.” Weaver said this about New England religion: “The right to criticize and even to reject the dogmas of Christianity came at length to overshadow the will to believe them.” That’s a tremendous statement. But I would ask how did the people not necessarily known for evangelical orthodoxy during the colonial period enter the Civil War era, as, in Weaver’s words, “one of the few religious peoples left in the Western world?” That’s a major question. And conversely, how did Puritan New England and the Greater North (or the Deep North) become, in so short a time, so unorthodox? These are questions beyond the scope of this lecture. Suffice it to say that the South was never as unorthodox as many believe during the colonial period, and the North, especially Puritan New England, was never as orthodox as we think they were.

One of the best ways to demonstrate this older religiousness that Weaver talks about is by looking at representative Southern theologians who had a lasting impact on the region. If we want to know what Puritans believed, for example, we should look at the writings of people like Cotton and Increase Mather and Jonathan Edwards. We almost automatically, for example, think of Edwards as America’s theologian. In fact, that’s what he’s called today. But it would seem that one of the criteria for choosing a representative theologian would be that his ministry had established an enduring culture in his own region. Whatever there was of a Christian culture in New England, it was gone within fifty years of Edwards’s death. That has to mean something, I think. Of course, the purpose here is not to present our subjects Thornwell and Dabney, as national or global anything. They would likely rise from their graves in protest. They were far too humble and locally-oriented to think in self-idolized global categories. My goal in this lecture, other than simply introducing you to the life and writings of these two remarkable Southern theologians, is to test the accuracy of Weaver’s assessment by using Thornwell and Dabney as the principle measurements. They were the two greatest Protestant theological minds in the South and arguably in the United States. My thesis is simple: Thornwell and Dabney illustrate admirably the older religiousness of the South as Weaver presented it.

Let’s start with Weaver’s first point, revelation and not negation. Weaver said: “Man cannot live under a settled dispensation if the postulates of his existence must be continually revised.” The late Chip Conyers tells of the Baptist leader in Texas, B.H. Carroll, that as a young, agnostic Confederate veteran, he was seeking religious truth after the War. In the midst of the turmoil of his life, he had tried to find solace in what he called anti-Christian philosophies. He had earlier admired these philosophies, he said, for what they destroyed, but now was looking for something to build him up. He needed help, he said, for a hungry heart and a blasted life. He embraced the Bible and Christianity and rejected other viewpoints because: “They were mere negations.” In the theological writings of both Thornwell and Dabney, we find this same settled, positive approach to theology, namely that Christianity at its core is a revealed religion, not subject to the whim of notion and negation. Religion based on modern reactions is no religion at all. It is rather a process of continuous elimination until nothing of substance remains.[4] In Dabney’s systematic theology, he stated in his section on the Trinity that the reason rationalists think they can negate the Trinity is because they think they can understand the Trinity. After a careful and deep evaluation of that doctrine in his systematic theology, Dabney wrote this: “I pray the student to bear in mind that I am not here attempting to explain the Trinity, but just the contrary. I am endeavoring to convince him that it cannot be explained and because it cannot be explained, it cannot be rationally rebutted.” Dabney saw this tendency, even in most of the orthodox of his Presbyterian brethren. Even the Northern brethren in the old-school Presbyterianism ran too quickly, he said, into the negative in their theologies. When Charles Hodge came out with his three-volume systematic theology (which is a wonderful systematic theology and Dabney liked most of it), Dabney wrote a fifty-page critique.[5] You can read it in Volume I of Dabney’s Discussions.[6] His main complaint with Hodge’s systematic theology was that it focused too much on the negative. He said: “The author displays the multifarious forms of error with more fullness than his own views of what is true.” In other words, Hodge was focusing too much on what was not true. Moreover, said Dabney, “His theology appears chiefly for the purpose of refutation.” In other words, it was not a positive theology. Now, don’t get me wrong. Dabney wasn’t always positive. He was an apologist and he attacked when attack was necessary. But he felt there had to be this positive approach to theology instead of focusing on what is not true.

I said to you earlier that Thornwell left Harvard as a young student because of Unitarianism., but the initial problem he had with their theology was not so much the content of what they believed, but in how and why they came to believe it. They were obsessed with what he called “a crude compound of negative articles.” That is, New England Unitarianism was reactionary to Trinitarian truth. It had no real foundations. The older religiousness at its core is based on truth accepted by faith, not figured out by reason, or worse, developed in negative reaction to something else. Though not pure fideists, Thornwell and Dabney did not believe you could allow reason to be the first principle and everything else deduced therefrom. If you did, then the miraculous, the unexplainable, etc. would negate truth claims altogether because some of those things just can’t be explained. After all, faith, by its very definition in the Bible, is “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.”[7] The newer religiousness, on the other hand (if we could call it newer religiousness), had little settled a priori doctrine; man was the ultimate decision-maker and could determine truth by his own rational standards. Thus, when something contrary to so-called reason made an assertion like the doctrine of the Trinity, it was simply negated and rejected. So, Unitarianism’s foundational doctrine is a negative, a rejection of a long-held faith dogma. Thornwell simply called it “pagan.” He also referred to Unitarians as atheists and identified one of the biggest problems of the War was between Christianity and atheism. Atheism, of course, is the ultimate negative – “no god.” While visiting Harvard in 1852, Thornwell attended a faculty commencement dinner. He informed his wife by letter: “They concluded the dinner by singing the 78th Psalm. This had been an old custom,” he said, “handed down from the Puritan Fathers. It was really an imposing ceremony and I should have enjoyed it very much if I had not remembered that they were all Unitarians witnessing in this very service to their own condemnation.” Psalm 78 is about passing on truth to your children, generation after generation. So, to Thornwell, the children of New England were doing what many of the children of Israel had done. They were staring Biblical truth in the face, even singing it, though they had long since abandoned it for a speculative theology born of their own devices. They were people of notions, not necessarily of truth.

So, negation of truth has no foundation. From the very start it is a theological disaster and is impotent to connect man to God. It only stands in opposition to something else. In Dabney’s words, “the attempt…fails; because error never has true method. Confusion is its characteristic.”[8] Today, modern theological writing, like most areas of academia, is considered productive if it is innovative. Thornwell and Dabney did not fall into that trap. Douglas Kelly said Dabney’s theological method displayed “contempt for all innovation and speculation.” Sometimes you will hear the phrase “doing theology.” For Dabney and Thornwell, you did not “do theology.” That is new and innovative theology. I do not mean that they shunned imagination and effective presentation of thought; all good writing requires both. But for them theology of all things was not for experimentation. Christian theology was about faithfully explaining revealed truth, not about the latest interpretive fad. They recognized that there was an inexhaustible supply of Biblical truth to expound and systematize. Where is their time, then, for innovation? Simply put, their contribution was that they did not seek to make a new contribution, but instead sought to be faithful to ancient truth.

Thornwell and Dabney were not pure dogmatists. The philosophical context of both men’s theological writings had deep roots, however, in philosophical realism, particularly in Scottish common-sense philosophy. This brings us to Weaver’s second point, that the older religiousness was also characterized by realism, what I would call Christian realism, a faith-based balance of reason, emotion, and creation. On the surface, Weaver seems to suggest that Southern religion paid little or no attention to reason. The Southerner, he wrote, did not want to reasoned belief, but a satisfying dogma. Although Weaver (possibly for effect) overstated his case here, he actually indicates a balanced understanding in the same article. What Weaver is talking about is that Southerners generally rejected what he called the spirit of rationalism. I don’t think Weaver is really saying they didn’t pay attention to reason at all, but they rejected the spirit of rationalism, and I would say Weaver saw the Southern propensity to appreciate nature as the glue that held faith and reason in a workable tension. Thornwell adopted the inductive methods of Scottish common-sense as a means to bridge reason, nature, and revelation. You might say that Thornwell was first-generation Scottish common-sense, and he learned it from Robert Henry, Professor of Logic and Ethics at South Carolina College. Henry had studied in Edinburgh and brought that mode of thinking to the Lower South. Thornwell read Dugald Stewart and Sir William Hamilton while at South Carolina.[9] E. Brooks Holifield called Scottish common-sense “the reliable handmaiden of Southern theology.” I think that’s an interesting statement. He said: “It was not so much a set of conclusions as it was a way of thinking, a philosophical realism, a Baconian method of induction to get one started in the process of investigation.”

In the first chapter of his systematic theology, Thornwell deals with the Being of God and immediately delves into Thomistic proofs of God’s existence: “we can know nothing aright without knowing God…He is the fountain to which all the streams of speculation converge. Truth is never reached…until you ascend to Him. Intelligence finds its consummation in the knowledge of His name.”[10] Note that Thornwell allows for “the streams of speculation,” but he said they converge at a prescribed point. A certain harmonious connection between faith and reason seems to offer the most satisfying approach for Thornwell – faith, reason, and nature all work together under God’s umbrella of authority. For many of Thornwell’s Northern counterparts, however, thinking was a constant process of dialectical compartmentalization, and when compartmentalization rules in theology, one is forced to go with one thing or the other, but not both. This is the definition, I think, of radicalism – it is the use of rationalism against reason. (By the way, reading both Thornwell and Dabney, I see echoes of John Randolph. Dabney really liked Randolph). Thus, starting with nature to discover the Being of God does not suggest that Thornwell was downplaying the Bible and revelation as the ultimate authority, but it does suggest that he did not fear an honest investigation of God’s creation. Like Thornwell’s colleague and friend the accomplished scientist Joseph LeConte wrote: “Nature is a book in which are revealed the divine character and mind. Science is the interpretation of this divine work.”[11] For Thornwell, the study of nature was not just about inquiry and proof. It was about magnifying God. It was about appreciation for nature, especially in that it was a vehicle of worship. In the second chapter of his systematic theology, Thornwell said: “These heavens and this earth, this wondrous frame of ours, and that more wondrous spirit within, are the products of His power and the contrivances of His infinite wisdom. Nothing is insignificant, nothing is dumb.”[12] If you know anything about New England Puritanism, that’s not normally how they approached nature. Realism informed Dabney’s approach to theology as much as Thornwell’s. Dabney, like both Catholics and Protestants before him, sought to understand natural theology so as to provide context for revealed theology. Dabney’s theological method essentially follows Thomas Reid in seeking to prove the existence of God not from a pure axiomatic position, but from the matrix of cause and effect, an inductive method. The first lecture in Dabney’s systematic theology is titled “Natural Theology,” and subtitled “The Existence of God.” In this and subsequent lectures, he argues for a balance between an intuitive and dogmatic approach of understanding God’s existence. Dabney’s biographer, Sean Lucas, said: “There was a consensus between God and human beings [for Dabney] that preserved the real action of both and yet gave God priority.” If you’re interested in how Dabney works out this thinking further, I would refer you to his book The Sensualistic Philosophy of the Nineteenth Century.

A very important topic when you’re talking about Scottish common-sense and these men is the topic of emotion. It was typical of old-school Presbyterianism, even those who intellectually espouse Scottish common-sense, to downplay emotion and religious expression. The main reason they rejected emotion was its association with new-school revivalism, but with Southerners like Thornwell and Dabney, who were themselves old school and didn’t appreciate a lot about the new-school movement, emotion was not so readily dismissed. To be sure, they rejected emotional excess, but emotion could be used for God’s glory. I like the descriptive of Thornwell that when you heard him preach, it was “logic on fire.” That’s how he was described. Somebody asked: “Who are the three great theologians of the South?” The person giving the answer replied: “Well, if you want great oratory, go to this person. If you want deep learning, go to this person. But if you want to blast rocks, go to Dabney.” For Dabney, it was vital that we understand the proper role of emotion. The soul was a unity and not subject to compartmentalization. Thus, to treat it in its unified complexity was to be faithful to reality. Dabney stood in stark contrast to the various forms of rationalist theology that presented man as an abstraction neutralized from the influence of feelings. Emotion gave context to cognition in Dabney’s thinking. In 1884, he reviewed James McCosh’s book, The Emotions in the Southern Presbyterian Review. In that review Dabney said: “Feeling is the temperature of thought.” That’s a really good review. You should go and read that.[13] I have some other quotations, but for the sake of time I’m going to skip them. For Dabney, the emotions were not all positive. There is a legitimate negative side to emotion, and for the sake of reality Dabney did not ignore or spiritualize it away. In his celebrated address, “The Duty of the Hour,” he spoke on the practical use of negative emotions: “In keeping with the law of man’s sensibilities, the natural reflex of injury or assault upon us is resentment. The man who has ceased to feel moral indignation for wrong has ceased to feel the claims of virtue.” Anyone who pretends to be “above anger makes me suspect that his virtue is not supernatural but hypocritical.” Dabney was what Samuel Johnson called a good hater. His Christian realism required him to be honest and not hide negative emotion. Now, he understood there was a limit to this, but I appreciate his honesty here, whether you agree with him or not. There is such a thing, too, in the Bible as righteous anger.[14]

“Be ye angry and sin not,” the Bible says.[15] Of course, Dabney is well known for not forgiving the North for the War and Reconstruction. He believed it was sinful to forgive those wrongs, mainly because of his theology. He didn’t believe you gave forgiveness until someone repented, and so he didn’t forgive. Now, whether or not we agree with that notion, it illustrates an important point about his theology. He sought to avoid the overreaching of positive sentiment when negative sentiment was more appropriate. He hated because he believed it was the orderly emotion called for when excessive wrong had taken place. Chip Conyers wrote that “incarnational sentiment,” was “the most essential character of religion in the American South.” He noted that Southern religion has always been dominated by a strain of theology that had a healthy respect for nature and human senses. I really do believe, the more I think about it, that the lack of this incarnational sentiment in New England theology is a key, if not the key, to understanding the difference between Southern and Northern, you could say Calvinism or Christianity.

That difference reverberates into many important areas, few more important than the question of religion’s role in a free society, and that brings us to Weaver’s third characteristic of this older religiousness. The older religiousness is reserved. Weaver did not mean that Southern religion was not politically and socially engaging. It was. But older religiousness in the South knew its role in society and by nature was in line with a decentralized and volitional approach to life, as opposed to being forced, imposing, and activist. There is a relatively new discipline in theological circles called public theology. According to Clive Pearson, the Associate Director of the Public and Contextual Theology Strategic Research Center (How’s that for a name?), public theology is: “Concerned with how the Christian faith addresses matters in society at large. It is concerned with the public relevance of Christian beliefs.” Now, to be sure, this area of public theology is somewhat on the chic and liberal and progressive end of evangelicalism and modern Protestantism. Conservative Protestants and conservative Catholics have been engaged in culture no a very high intellectual plane since the church started, but now that progressives do it, it becomes a respectable discipline. Thornwell and Dabney were public theologians par excellence, so a good example of public theology is reading Dabney’s Discussions on all different types of topics, because he brings theology to bear on just about everything. Their theology was in every way intellectually informed, but it was not for the ivory tower, nor were their writings spiritual as opposed to secular. To them all, ground was holy ground; every bush was a burning bush. Dabney, for example, saw theology as a luminating corrective in society. Whenever he wrote on secular themes such as economics, history, and psychology, you see this coming through. And again, I would refer you to his Discussions, especially the volume called Discussions, Secular. Both men also believed that the reach of religion had limits in a free society. They saw ecclesiastical centralization as a reflection of the problem as it existed in the broader political climate.

Some believe, for example, that Southern Presbyterians separated from the Northern church. In fact, it was the opposite. The Southern church was literally forced out. In May 1861, the Gardner Spring Resolutions came down from the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States, meeting in Philadelphia, requiring loyalty to the Federal government, and they were careful to define what they meant by the Federal government: “That central administration as the visible representative of our national existence.” They were saying that the executive branch is the Federal government and you must swear allegiance to Lincoln. Note that the Constitution was not the ultimate authority here, but the executive branch. After the successful Gardner Spring vote, Charles Hodge, to his credit (the Southern ministers were not there for obvious reasons), led forty-seven others in dissenting, saying the assembly had veered into political territories it had no business embarking on. Protesters against Hodges dissent said: “Would they have us recognize, as good Presbyterians, men whom our own government, with the approval of Christendom, may soon execute as traitors?” This shows a dark side if I ever saw one. These “good Presbyterians” are thinking execution for their Southern brethren, execution sanctioned by the church. In December of 1861, the Southern Presbyterians convened their own General Assembly of the Confederate States of America in Augusta, Georgia. The moderator, Benjamin Palmer, said: “They were compelled to separate themselves in order to preserve the crown rights of the Redeemer and the spiritual independence of His kingdom and the church.” It was in this meeting that Thornwell gave his famous address to all the churches of Jesus Christ throughout the Earth. In this address he gave two reasons why the churches should be separate (other than the most obvious, that they had been kicked out). Thornwell took the high road here and offered a very irenic remedy in the spirit of Christian consensus: “The unity of the church does not require a formal bond of union among all the corrugations of believers throughout the Earth.” In other words, churches can be in spiritual union without one segment trying to unduly control the other, because the Bible does not command such control. Likewise, separate nations can be friends, he argued, and there is no reason that their churches cannot be mutually supported. You might think of Thornwell’s perspective in terms of a Jeffersonian strict constructionism. Thornwell’s decentralization was informed by his strict adherence to the Bible. As Douglas Kelly has written, Thornwell’s basic assumption in developing his arguments was the hermeneutical principle that whatever is not commanded in the Bible is forbidden. Sounds like a Jeffersonian view applied to the that question, doesn’t it? Strict constructionists are by nature, decentrists so that, among other things, power hungry interlopers cannot usurp the authority that belongs to a settled compact. What worked in the church, worked in the state, but not when either tried to cross into the other’s sphere of authority. Likewise, for Dabney, the entire War Between the States hinged on the problem of centralization. In his article “The True Purpose of the War,” Dabney wrote that the Republican war party was not the party of union, but “the party of Federal usurpation and centralization.”[16] If you really want to read a fascinating thing, read his narrative of Colonel J. B. Baldwin and Baldwin’s meeting with Lincoln.[17] For Dabney the issue was just as much theological as it was political. In fact, the two went hand-in-hand.

Dabney’s theological and secular writings are imbued with Liberty as God-given and sacred. In Dabney’s response to the Gardner Spring Resolutions, he said that the assembly’s decision was unrighteous, unconstitutional, and in its own nature, divisive of the church. These Northern brethren were wrong in making secession sinful. The whole affair “cannot be a proper subject for church censures.” Conversely, Dabney believed that to not give allegiance to the State above the Federal Union was itself sinful. So, bound by theology and conscience, Dabney eventually saw no alternative but to secede. It should be remembered that Thornwell and Dabney were not what you would call fire-eaters. They both sought ways to prevent secession of the States. In this respect, I think they were followers of Calhoun’s and Randolph’s larger principles of union. However, they saw Liberty as more important than union. Union was a civil agreement among the States created in the Constitution. Liberty was a gift from God protected by the Constitution. The very idea that a God-given precept like Liberty depended on a man-made concept like union was ludicrous to someone who understood the Christian principles of government. Be that as it may, once secession was declared as the Southern States best means to preserve Liberty, both Thornwell and Dabney felt a holy obligation to support the decision. They did this not only as good citizens of their respective States, but as active Christian theologians. They supported secession not just for regional or heritage purposes, but because Christian theology taught them that centralized power brings out the excesses of sinful humanity. Secession, like everything else with Thornwell and Dabney, was, in the end, a theological decision.

In conclusion, I want to say that at the beginning of this paper, I mentioned that Dabney and Thornwell impacted their culture in a lasting way. Maybe that’s backwards, or at least the wrong emphasis. One of the most important questions, maybe the most important question we can ask about religion in America, is this: “Why did orthodoxy take root and remain in Southern culture unlike anywhere else in America and even the world?” I’ve talked about things like the impact of Scottish common-sense on men like Dabney and Thornwell, but as real as these outside influences were on both of these men, I really don’t think that this takes us far enough. Many, for example, were influenced by Scottish common-sense with very different results. As Clyde said yesterday in his talk on M.E. Bradford, ideology does not create a society, and I’d say philosophy doesn’t either. Philosophy or ideology must first go through the filter of culture. Culture establishes for the individual what is important, what should be sought after, and what should be shunned. Culture births, incubates, and matures desire. Culture and place provide the necessary context that gives meaning. Or should I say reality? Thornwell and Dabney rejected innovation and negation and accepted revelation. They rejected abstraction and compartmentalization and adopted reality. They rejected centralization and force and embraced a reserved posture of faith. But why? I would suggest that the secret lies in what Dr. Wilson was talking about on Bradford, this wonderful definition of the South that Bradford gives: “A vital, long lasting bond, this corporate identity assumed by those who have contributed to it.” What is this vital, long lasting bond? What is its makeup? How do we discover it, understand it? Well, I think one of the best ways is to do what we’re doing this week. To go to the text. To seek to understand and appreciate who these people are, what they were thinking, what they were writing, and why they were writing it. And I would say if you want to understand the older religiousness of the South, I can’t think of a better place to start than with James Henley Thornwell and Robert Lewis Dabney. Thank you.

[1]Based on an examination of their website, Banner of Truth Trust’s Collected Works appears to be out of print. However, much of Thornwell’s work can be found for free online. For example, Thornwell’s Collected Writings, first published in four volumes from 1871 to 1873, can be found here: https://archive.org/details/collectedwriting0001thor/page/n9/mode/2up https://archive.org/details/collectedwriting0002thor/page/n7/mode/2up https://archive.org/details/collectedwriting0003thor/page/n5/mode/2up

https://archive.org/details/collectedwriting0004thor/page/n7/mode/2up

[2]Mrs. Jackson’s Memoirs of her husband came into print twenty-nine years later. For Dabney’s Defence of Virginia, see: https://archive.org/details/defenceofvirgini00dabn/page/n1/mode/2up For Dabney’s Penal Substitution, see: https://archive.org/details/christourpenalsu0000dabn/page/n5/mode/2up

[3]It’s an article well-worth reading.

[4]Postmodernist deconstructionism is a perfect example of this.

[5]For Volume II, see: https://archive.org/details/systematictheolo02hodg/page/n5/mode/2up For Volume III, see: https://archive.org/details/systematictheolo03hodg/page/n5/mode/2up

[6]The critique originally appeared as a book review in Southern Presbyterian Review, April 1873.

[7]Hebrews 11:1, KJV. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Hebrews%2011%3A1&version=KJV

[8]See Dabney’s Systematic Theology, 2nd Edition, page 6: https://archive.org/details/systematictheolo0000dabn/page/6/mode/2up

[9]For The Collected Works of Dugald Stewart, see: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Collected_Works_of_Dugald_Stewart For Hamilton’s Discussions on Philosophy, see: https://archive.org/details/discussionsonphi00hamirich/page/n7/mode/2up For Volume I of Hamilton’s Lectures on Metaphysics and Logic, see: https://archive.org/details/lecturesonmetaph0001hami/page/n5/mode/2up

[10]See Thornwell, Collected Works, Volume I, page 66: https://archive.org/details/collectedwriting0001thor/page/66/mode/2up

[11]Joseph LeConte, “Lectures on Coal,” Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution (Washington, D.C.: 1857), page 119: https://archive.org/details/annualreportofbo1857smit/page/118/mode/2up

[12]See Thornwell, Collected Works, Volume I, page 63: https://archive.org/details/collectedwriting0001thor/page/62/mode/2up

[13]Southern Presbyterian Review, Volume XXXV, page 369: http://library.logcollegepress.com/Southern+Presbyterian+Review%2C+Vol.+35.pdf

[14]See, for example, Matthew 21:12-17, John 2:13-17, Esther 7, Nehemiah 5:1-13.

[15]Ephesians 4:26, KJV: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Ephesians%204%3A26&version=KJV

[16]See Discussions, Secular, page 101: https://archive.org/details/discussions04dabn/page/100/mode/2up

[17]See Discussions, Secular, 87-100.