Some twenty years ago I had planned to write a full-length study of John Pelham—known in the South as the Gallant John Pelham—and the making of myth. The business of earning a living and other distractions, however, intervened to keep that project from being completed. I finally abandoned it as a lost cause of my own. Recently, however, I came across a notice of a book on the Alabama artillerist entitled The Perfect Lion, by Jerry H. Maxwell (University of Alabama Press, 2011). I gather that it is the very sort of book I had aimed to write.

Which brings us to my theme today: John Pelham and the “myth” of the Lost Cause. Now, to clarify and to anticipate the rest of this essay, I have to say that there are two versions of the Lost Cause. One of these originated in the original states of the Southern Confederacy. The other version originated north of the old surveyor’s line a bit later. That’s the Yankee version.

Put briefly, the Southern version holds that while the South was defeated in the War Between the States, the cause for which it fought was noble and some would even say sacred. The main issue at stake was regional self-determination, mostly political and economic. Some refer to this as states’ rights, the self-governance of the states in their relation to the central government. Slavery was an institution of long-standing for the presence of which both North and South had responsibility. It was New England ships after all that brought slaves to American shores. Finally, only a minority of Southerners owned slaves.

The Northern version is that the so-called Lost Cause is a myth in the sense that it is based not on historical fact but rather on wishful, sentimental, and self-justifying thinking developed after the fact of a bitter defeat. The real issue of the War was slavery, which the North sought to expunge from the face of the earth. The cause of states’ rights was conjured up as a smoke screen to distract from the real motivation, the preservation of the “peculiar institution.”

Certain qualifications could be added to either of these simplified accounts based on differences of opinion articulated at the time—and later—within each region. The Union, for instance, was important to many on both sides. Not everyone in the South defended slavery or wanted to secede. Not everyone in the North saw slavery as purely evil, and some were willing to let the South go its own way. Nathaniel Hawthorne was a prominent example of one of these.[i] But the basic outlines sketched here should be clear and fair enough.

To return to John Pelham and the concept of myth, I want to make clear what I mean by “myth” in this context. It is certainly not the Northern version of the term as it is applied to the Lost Cause. As I use it here and as it generally applies in serious literature, it means essentially a story about a people which is based in reality but which may include appropriate enhancements of imagery, action, and character that lend interest, verve, and meaning to the basic narrative. Its main function is to convey a truth that cannot be properly transmitted in any other way. The Homeric myths, which form the basis of the Iliad and the Odyssey, may serve as a case in point. While these stories cannot be traced definitively to established historical events, the heroes of those poems were arguably based on real soldiers who were enlarged, ennobled—or in some cases derogated—in the rendering of their exploits by the poet.

And even so unprepossessing an anti-hero as Leopold Bloom in James Joyce’s Ulysses is enhanced by parallels made by the author to the actions of the original hero, even as Bloom falls far short of that figure at the same time. Examples could be added indefinitely. To cite one other closer to home, we can name “Stonewall” Jackson. That particular sobriquet was coined at First Manassas when Jackson’s Virginians held firm in the battle against a murderous onslaught. General Bee declared that they were standing like a stone wall, just moments before he himself entered eternity from a fatal wound. Hence, the name, of which Jackson himself, dour Presbyterian that he was, did not particularly approve.

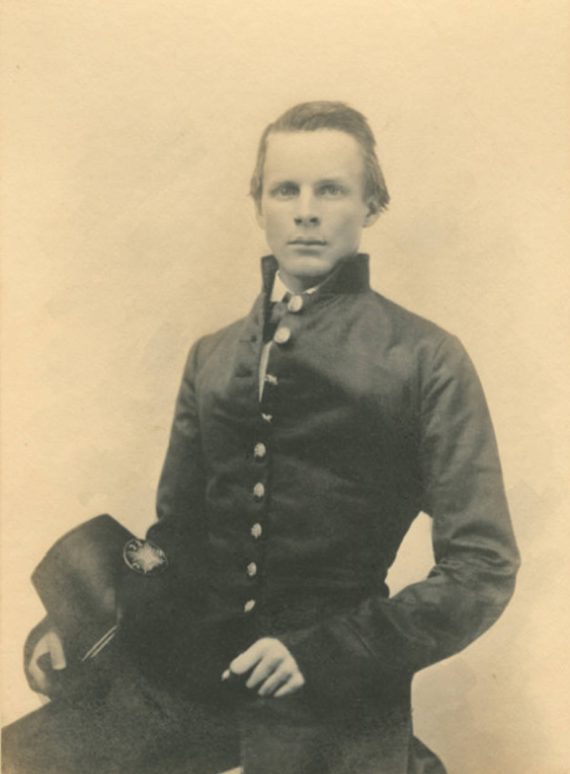

I earlier referred to Pelham as the “Gallant Pelham,” a name he rightly earned. But it partakes of just the same sort of enhancement that gave Jackson his special designation. And it is a name that derives perhaps in Pelham’s case not only from exploits on the field of battle but those more gentle ones that unfolded while courting the fine, young ladies of Virginia. Pelham and his Horse Artillery fought in some sixty battles or skirmishes before his death following Kelly’s Ford in March of 1863; according to various accounts three young women went into mourning on learning of his passing. That latter report may or may not be accurate. I’m not sure. But let us say that the title was fairly earned in any case.

And it was both earned and bestowed, that is by those who could best appreciate his military prowess. His most notable military action was probably that at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December of 1862. But beforehand, at Gaines Mill (June, 1862) General Stuart had referred to the performance of “the noble captain” in that engagement as “one of the most gallant and heroic feats of the war.” At Fredericksburg itself, Stuart again expressed his admiration for the Alabama warrior, but it was the more effusive words of R.E. Lee which crowned his head with glory. We know them now by heart. Echoing the sobriquet of Stuart, he said of the “gallant Pelham,” “It is glorious to see such courage in one so young!”

The point I wish to make here is that myth and myth-making in this context is a not matter of fiction, fantasy, or falsification. Rather, it a phenomenon consisting of two parts: superlative achievement and superlative language applied to it to give it its full due. The action comes first, of course; but the words must follow in order to capture, communicate, and perpetuate its meaning. We see the process at work again and again in any number of cases of those who fought for both North and South. Only, when it comes to our heroes, the Northern, liberal mentality does not want us to have them.

As regards John Pelham and the myth of the Lost Cause, one will never convince the dyed-in-the-wool far-left Northerner, some of them descendants of New England Puritans, that there was anything noble in the life and actions of John Pelham or of any other Confederate figure. Driven by an ideology fed by Gnosticism, they have to be right and you (as a Southerner) have to be wrong.[ii] No two ways about it. And not only that, but the fact that you see in those who fought on the Southern side and in the cause itself some redeeming and noble elements means that both you and they must be destroyed. Or as they say these days “cancelled.”

Such a mentality parallels so-called Critical Theory, derived from the matrix of cultural Marxism, that is abroad in the country today. According to this mindset, there are two classes: the oppressed and the oppressors. If you are white, straight, affluent, male, or some combination, you are the oppressor. If you are black, poor, gay, female, or some combination, you are the oppressed. It is not, to those who hold this view, debatable. There is no counter argument; there are no facts, no logic, there is no objective reality that can be used to dispute this ideological viewpoint. And that is what it is, poisonous ideology. You can tell you’re facing an ideology when spokespersons for it declare that they are indisputably right and that you must capitulate. That way lies madness, of course.[iii]

Like virtually every ideological construct, this one involves a fatal internal contradiction. It says, first of all, that there is no such thing as objective reality or objective truth. There are only “positional” truths. Only those who occupy a certain position or identity—black (or some other minority), female, etc.—can speak truth. But what they don’t acknowledge is the hidden assumption that, somehow in their “wokeness,” they have totally cornered indisputable truth unto themselves solely by virtue of their arbitrarily pre-determined positions. This mindset exhibits, however, not merely, a self-defeating logical fallacy. It manifests what I term pathological hypocrisy. Moreover, it is the pathetic refuge of the intellectual coward and fraud.

It should be clear from this description that, one, we as Southern conservatives do not want to coddle such thinking and, two, that people who think that way have absolutely no ability to understand let alone appreciate the myth-making process, based in historical fact, that gave us the Gallant John Pelham. What they do not appreciate, moreover, is that part of what gives us our identity still today is heroes like Pelham, Stuart, Jackson, and Lee. Or perhaps they do. That’s why they want to cancel both them and us. We must be like them or be destroyed.

We are not so arrogant, however, as to insist that they too must honor these men and others like them. Of course, we do not need their help in any event. It should be clear by this historical juncture that what they object to is not simply the honoring of Confederate heroes or the Lost Cause. Witness various recent attacks (in 2020 alone) on statues honoring such figures as Columbus, Junipero Serra, and Col. Robert Shaw and his black soldiers. What they object to is history itself; that’s what they want to destroy. Why? Because history is complex, challenging, difficult, full of nuances, differences of opinion, and strong and difficult men and women who disagree among themselves. Many historical figures—most?—are not ideal role models for ideological fanatics. They are not formed of a clay that is easily manipulated by their woke ideology. They want a clean slate on which to rewrite humanity and society from scratch.

What we need today more than ever are men and women who, while recognizing flaws in our ancestors and historical personages in general, honor what is honorable in them and strive with courage, grace, and intelligence to emulate and defend them with whatever gifts they are given and follow humbly in their footsteps. The people I have in mind belong to those “generations of the faithful heart,” of whom Donald Davidson wrote in “Lee in the Mountains.” Perhaps there are those reading this who will answer the challenge. In doing so, they should remember with T.S. Eliot that there are no lost causes because there are no ultimately gained causes. In this endeavor we all could do far worse than to take John Pelham as one of our models.

[i] Marion Montgomery, in Why Poe Drank Liquor (LaSalle, IL: Sherwood Sugden and Company, 1983), 40, cites Hawthorne at the outset of the War: “Whatever happens next, I must say that I rejoice that the old Union is smashed. We never were one people, and never really had a country since the Constitution was formed.”

[ii] Gnosticism is both an ancient and modern heresy, both religious and secular in its multi-form manifestations. In essence, it seeks knowledge by way of the rational intellect at the expense of intuition, “heart,” or what Aquinas calls intellectus. It does so, generally, in its quest for power over being and ultimately over people. Eric Voegelin has analyzed the nature of the beast with great insight in The New Science of Politics and other works. See The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin: Volume 5, Modernity Without Restraint, ed. Matthew Henningsen (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2000).

[iii] I owe much of this commentary on Critical Theory to a piece by Grace Daniel (a pseudonym), “My Woke Employees Tried to Cancel Me. Here’s How I Fought Back and Saved My Non-Profit,” The Daily Signal, June 7, 2021. https://www.dailysignal.com/2021/06/07/my-woke-employees-tried-to-cancel-me-heres-how-i-fought-back-and-saved-my-nonprofit/?utm_source=TDS.

My family lines at the time of the WBTS are all from NE Alabama, NW Georgia and southern Tennessee. More of my ancestors fought for the north than for the south. I will not dishonor any of them for the decisions they made when the time came. I know one thing for a certainty, the ones who signed up to fight for the north wanted to maintain the union and didn’t fight because they wanted to end slavery. My three 2nd great grandfathers who fought for the south were not fighting to perpetuate slavery but because they were being attacked and invaded by the north. All my family who fought were too poor to own even one slave, but they were not too poor to take up arms to defend their country/state.

I believe the south was more valuable to Lincoln for tax collection purposes operating with slaves than without them. That’s why he said if he could maintain the union without freeing any slaves he would do so. Only when it became obvious that the south might actually win, did the the focus shift to fighting the war to free slaves.

What we’re seeing in the country today is generations of people who have ZERO knowledge of founding principles being brainwashed by the Marxists running government schools who have been chipping away at the foundation of the country ever since the Republic died at Appomattox Courthouse in April 1865. Without a heritage every generation starts over. Educated your family.