Oct 12, 1861, Confederate ambassadors James Mason and John Slidell set sail for England, Mason to be Minister to England and Slidell Minister to France. They were bound for England via Cuba where they boarded a British packet ship the HMS Trent. Was it mere coincidence that a Union warship, the San Jacinto, was notified by the US Consul in Cuba of the Trent’s departure for England, and that the Union ship’s Captain decided to break Maritime Law, intercept the British ship, and take the two Confederate diplomats captive?

The two prize captives were taken to Massachusetts November 2, 1861, where rousing cheers and accolades from the Lincoln administration greeted the Union Captain. At least up until the British Government’s Prince Albert sent a “sharp response” to Lincoln’s government demanding an apology and the release of the commissioners within 7 days. Otherwise, war would be declared, and the Confederacy would be immediately diplomatically recognized. British Lord Palmerston convened a special cabinet committee to prepare for war with the U.S. and ordered reinforcements to Canada and the British Atlantic fleet.

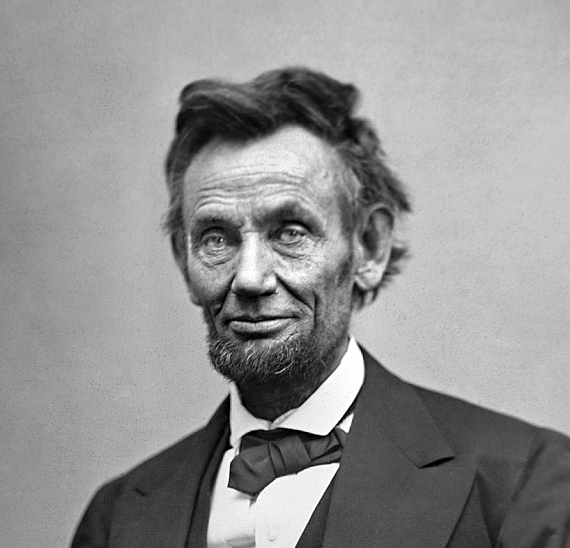

Back peddling cowardly like a child caught with hand in the cookie jar, “Honest Abe” proclaimed to the world that the Union Captain had “acted on his own” in stopping that British ship and taking the two diplomats in violation of law. The Union Captain, previously rewarded, was then made the scapegoat and punished for his actions.

British records reveal that Lincoln was lying about the Union Captain acting on his own. In a letter from Viscount Palmerston to Queen Victoria, November 29, 1861, the following is written:

“…. General Scott, who has recently arrived in France, has said to Americans in Paris that he has come not on an excursion of pleasure, but on diplomatic business; that the seizure of these envoys was discussed in a Cabinet meeting in Washington, he being present, and was deliberately determined upon and ordered…”

It was no coincidence that the Union Captain just happened to act on his own and stopped a British ship which just happened to have on board two CS ambassadors. It was all ordered by Lincoln!

Secretary of State William H. Seward, negotiated with the British to a compromise, and the Confederate Ambassadors were released on January 1st, 1862. A British Government steamer was sent to Massachusetts to receive the CS dignitaries, sailing to England arriving the last week in January 1862.

The question is why was Lincoln so intent on stopping the two CS ambassadors that he would break the law and risk war with Britain? Evidence strongly suggests Lincoln feared they might be offering emancipation to gain European allies. During the time of the CS Ambassadors captivity, word was circulating that the CS might emancipate its slaves. That could open the door for Britain and France to ally with the CSA. On November 12, 1861 a newspaper titled “The Express” published the following:

“The secessionists of Maryland are openly reviving a speech of General Toombs, an authority as high as Jefferson Davis himself, in which he reminded Congress, two years ago, that the South always held in her own hands the power of emancipation as an ultimate recourse…. It is at present declared by secessionists that it will be the policy of the Confederates to abolish slavery rather than yield to the North the opportunity of doing it.”

On November 30, 1861 a British paper called “Once A Week,” provides an early indication of Southern willingness to emancipate stating, “the Confederate authorities are already saying publicly that the power of emancipation is one which rests in their hands; and that they will use it in the last resort.” Obviously, a lot of Confederate emancipation rumors were stirring.

Could it be that an offer to end slavery in exchange for European alliances was being carried by the CS ambassadors? There is good evidence that was the case, which would explain Lincoln’s desperation to prevent the CS diplomats from reaching England. Was it mere coincidence that the same week the CS ambassadors Mason and Slidell arrived in England, a pertinent article broke in a British newspaper called “The Spectator.” It spelled out, in the kind of detail that belies rumor, what it called “that indirect but accurate way in which great facts get abroad;” certainly a description of communications carried by ambassadors. The following secretive treaty offer had been leaked to the press:

“the Confederacy have offered England and France a price for active support. It is nothing less than a treaty securing free trade in its broadest sense for fifty years, the complete suppression of the import of slaves, and the emancipation of every negro born after the date of the signature of the treaty….”

“The Spectator,” even though an anti-South newspaper, affirmed the reality of the CS offer to free the slaves. Would an anti-South newspaper have ever broke such a story favoring the South in the eyes of British readers were it not convinced of its credibility? It says the offer originates from “the Mississippian,” an obvious reference to CS President Jefferson Davis.

A February 17, 1862 entry in the diary of Lincoln’s ambassador to England, Charles Francis Adams, says the following:

“A visit from Bishop McIlvaine, who came to tell me the result of a conversation he had held at breakfast with Sir Culling Eardley this morning, that gentlemen had apprised him of the existence of rumors that Mr Mason had brought with him authority to make large offers towards emancipation if Great Britain would come to the aid of the confederates. He even specified their nature, as for example, the establishment of the marriage relation, the restoration of the right of manumission, and the emancipation of all born after a certain time to be designated.”

Adam’s diary entry also says that the offer “needed to be energetically treated both here and at home.” Allowing for the eight or so days needed for Adam’s to communicate across the Atlantic, and a few days to put together a plan, is it mere coincidence that on March 7, 1862 Lincoln sends a resolution to Congress offering something he had up to then resolutely resisted doing. Lincoln had long resisted a general offer of compensated emancipation because of his fear, and the fear of his constituents in the North, that freed blacks might migrate North. But now it appears, to head off the rumored CS offer to end slavery, Lincoln offers all the slave States compensated emancipation, even without a colonization plan in place. He certainly had to be greatly concerned to do that! But from the slave States he gets no response. Meanwhile the CS offer to end slavery is hitting newsstands around the world.

So, on July 12, 1862 Lincoln calls a meeting with the border slave State legislators trying to convince them to accept his offer. They vote down his offer 20-8. Seven of the eight who voted for his offer to emancipate explain why:

“We are the more emboldened to assume this position from the fact, now become history, that the leaders of the Southern rebellion have offered to abolish slavery amongst them as a condition to foreign intervention in favor of their independence as a nation. If they can give up slavery to destroy the Union; We can surely ask our people to consider the question of Emancipation to save the Union.”

These border slave State legislators, who called the CS offer a “fact, now become history,” were in a position to confirm the secretive CS offer as “fact” given they were in continuous communication with the leadership of those seceded sister slave States who were trying to get them to join the Confederacy. Would these Union loyal legislators have ever told their President during a time of war, that a matter of such strategic importance was a “fact” if they had not confirmed it? They at least convinced Lincoln it was a fact. For it is not mere coincidence that the very next day after meeting with those seven legislators, July 13, 1862 Lincoln sat down and drafted his “Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.” No wonder Lincoln called it a “war measure” intended to keep Britain and France out of the war. Once again, he was attempting to preempt the Confederate offer of emancipation, but this time believing it to be a “fact” instead of mere “rumor,” Lincoln had upped the ante of his compensated emancipation “offer” to a mandatory “proclamation” of uncompensated emancipation freeing the slaves under Confederate control.

One thing can be certainly deduced from all these too “coincidental” actions of Lincoln. His desire to emancipate was a reaction to the Confederate offer made January 1862, and in no manner was he motivated by a genuine concern for the slaves. Another certain deduction from the Confederate offer to emancipate is that the Confederacy did not secede and fight to perpetuate the institution of slavery.

Great research

the yankee propaganda to me is just sickening….the running of slave ships from Yankee ports (according to a prominent black writer) in the international slave trade into the early 1860s, the shyster lawyer lincoln wants to remove blacks from uSA, feels they are inferior and can never be part of the American ‘polity’ and northern states some 30 some years prior (well within the mystic chord of memory timeframe) threaten secession ‘again’…and the south are called traitors and in rebellion for just leaving. rebellion? from multitudes of german 48ers fresh from having their asses kicked and having complete knowledge of American political history? at this point the term rebellion is an affront. read re lees anguish at having to resign and likely enter war….nothing close to rebellion. to hell with Illinois lawyers. https://www.abbevilleinstitute.org/the-preacher-who-stole-lincolns-past-by-the-carload/

I KNOW I AM PREACHING TO THE CHOIR, BUT THIS SOON TO BE PUBLISHED BOOK (SUPPLY CHAIN & $$$ DELAYS) SHOULD BE IN EVERY INSTITUTION OF LEARNING STARTING IN KINDERGARTENS!!

Dr. Kevin Orlin Johnson, Ph.D., author of The Lincolns in the White House: Slanders, Scandals, and Lincoln’s Slave Trading Revealed, began his search for thousands of missing papers of President Abraham Lincoln in 2009, as preparation for his book.

Lincoln married Mary Todd of Illinois, a prominent family and owner of many slaves. The decades-long settlement of the Todd estate left thousands of court documents, Johnson says. “But for more than a century Lincoln Studiers have been searching through those archives: documents about slavery were prime targets for destruction or theft.”

Johnson started searching the private collections of prominent Lincoln Studiers of the past, such as William H. Townsend of Lexington, Kentucky, and the notorious Rev. William E. Barton, whose plunder filled several railroad boxcars when shipped to the various libraries mentioned in his will. Sure enough, Johnson found the document in a dusty box at the Regenstein Library of the University of Chicago, uncatalogued since it was bequeathed to the library in 1930.

The affidavit was written in 1850 by the family attorneys Kinkead and Breckinridge ― John Cabell Breckinridge, who’d run against Lincoln for the presidency a decade later. It’s the Lincolns’ answer to a Bill in Chancery filed in Fayette County about the disposition of the property that the couple had inherited from Robert Todd. It certifies that Lincoln and his wife “are willing that the slaves mentioned in the Bill shall be sold on such terms as the Court may think advisable.”

What a great piece.

James Buchanan (the 15th president) has been much maligned in history. He was, in my opinion, the last truly Jeffersonian president, although an extremely weak one. Buchanan didn’t believe in secession AND he didn’t believe the Federal government had any right to wage war against any state that seceded. He did nothing to ameliorate the situation after the November Election of 1860; because of this, he is belittled in the records.

The time period between the November election of 1860, and March 4, 1861, when Lincoln became president was A VERY LONG TIME and a lot happened. Lincoln began acting-out as the president without regard that Buchanan was still the president. From December 20, 1860, through February 1, 1861, seven Southern States had seceded and on February 8, 1861, a new country was born – the Confederate States of America!

So, ‘what if…’

Buchanan had found a backbone and recognized the seven seceding states AS A Country. Where would that have put Lincoln? Perhaps the European nations, like England and France, would have given diplomatic recognition by March 4th and Lincoln’s call for troops would have taken on a very different scope and meaning; one that any war was indefensible and unnecessary, besides being an invasion of a sovereign country, which would most surely precipitated England’s participation with the South. With the call-to-arms after March 4th, Lincoln would have been seen as the ‘lawless one’ and would have faced a very different and hostile remaining country and a guarantee that he would have lost the election of 1864.’ (So much for his Divine Zeus Temple in Washington and his holy visage on Rushmore)

The outcome would have been very different and much more palatable to the South…

…but then, I’m just musing. Or, maybe, it’s wishful thinking of what might have been?