In today’s fast-paced society, much communication has been truncated into a few hundred ”tweets.” Far too many words have been needlessly abbreviated. All manner of proper names reduced to acronyms and newscasts have become little more than a cacophony of biased sound bites. Even the concept of history has fallen victim to this maddening trend, with the complexities of major historical events now presented in s few catchy phrases. An excellent case in point would be the War of Secession.

The full account of the years of turmoil that led to the secession of the Southern states, 1861’s actual casus belli, the events of the war, the twelve years of Northern occupation and the decades of recrimination that existed prior to the period of reconciliation that finally emerged at the start of the Twentieth Century are now being relegated to a few dusty footnotes of history. All the public hears today is that the North fought only to free the slaves and the South started the war merely to defend the institution. Furthermore, all those in the South who were once honored as American heroes are now being portrayed as racist traitors who must be removed from the public’s view and memory.

Even though the issues involving slavery played an important role in the secession of the Southern states, it certainly was neither the cause of the war nor the North’s invasion of the South. When President Lincoln issued his call for seventy-five thousand troops following the South’s secession, he did so for the stated purpose of quelling “the rebellion against the authority of the Government of the United States” and falsely based his action on the Insurrection Act 0f 1807. Lincoln also admitted publicly that the huge loss of federal revenue created by the departure of the Southern states would bankrupt the Union and could not be tolerated.

Therefore, an honest appraisal of history would bear out the Southern position that the North’s effort to preserve the Union and its funding, not the abolishment of slavery, was the true basis for the war. While that rational outlook was also shared by most informed people in Europe, particularly those in Great Britain and France, there was one voice in London that disagreed with the concept and claimed that the war of 1861 was solely a conflict between labor and capital, and one that demanded the freeing by the North of all enslaved workers in the South. The voice of dissent was that of communism’s founder, Karl Marx.

In 1848, what was to become one of the world’s most influential political documents, the “Manifesto of the Communist Party” by Marx and Frederich Engels, was published in London. Four years later, Horace Greeley, the publisher of the “New York Daily Tribune,” a paper with definitely socialist views on many issues of that day, hired Marx as its London correspondent. For the next ten years, Marx wrote some five hundred articles for Greeley on events in Europe, as well as injecting his own radical political and social views, many of which appeared on the paper’s front page. With a daily circulation of over two hundred thousand readers, as well as being the virtual house organ of the new Republican Party, Marx’s views had a wide and important audience in the North . . . one of whom being Abraham Lincoln.

At that time, while the socialist movement had been sweeping through much of Europe since the end of the Eighteenth Century, most of its concepts had very little impact in the United States. However, the influx of radical socialists from Germany in the decade prior to the War of Secession had a strong effect on political thinking in America, particularly in the North.

Many of the former German revolutionaries were followers of Marxist communism and became avid supporters of the Republican Party. While the members of the Communist League in America were active in Lincoln’s 1860 election, those who remained in Europe worked to prevent recognition of the Confederacy by Great Britain and France. After the start of the war, as many as two hundred thousand German immigrants joined the Union Army, with some of the communist leaders rising to high rank, such as Joseph Weydemeyer who was appointed colonel of a Missouri regiment and August Willich who was brevetted a major general.

Lincoln, of course, was not an actual communist, or even a true socialist, but many of his remarks on labor and social issues did reflect the views expressed by Marx. An example of that can be seen in Lincoln’s first State of the Union message to Congress in December of 1861 in which the president stated, “Labor is prior to, and independent of, capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital and deserves much the higher consideration.”

During the previous year, in a campaign speech in Hartford, Connecticut, Lincoln stated, “I’m glad to know that there is a system of labor where the laborer can strike if he wants to. I would to God that such a system prevailed all over the world.” In an even more Marxist vein, at an 1864 meeting with the socialist Workingman’s Association in New York, a group with which Marx worked closely in London, Lincoln said, “”The strongest bond of human sympathy, outside of the family relation, should be one uniting all working people, of all nations, and tongues, and kindreds.” This clearly echoed Marx’s famous slogan, “Workers of the world unite.”

In another speech, Lincoln employed the same sentiments as those expressed by Marx when he stated, “Inasmuch as good things are produced by labor, it follows that all such things of right belong to those whose labor has produced them. But it has so happened, in all ages of the world, that some have labored and others have without labor enjoyed a large proportion of the fruits. This is wrong and should not continue. To secure to each laborer the whole product of his labor, or as nearly as possible, is a worthy object of any good government.”

Like Marx, Lincoln was also a strong proponent of the type of centralized governmental authority that has grown exponentially over the ensuing century and a half. During the war, many who opposed Lincoln’s policies were imprisoned without trial and his Legal Tender Act of 1862 put a half a billion dollars of unsecured federal currency into circulation. That Act was the forerunner of the present Federal Reserve Notes and the government’s unlimited printing of money backed by nothing more than faith and credit.

Furthermore, Lincoln’s views on the role of the federal government not only coincided with those of Marx and the socialist groups that then supported the Republican Party, but his Marxist statements on the subject, such as “The legitimate object of government is to do for a community of people, whatever they need to have done, but cannot do for themselves in their separate and individual capacities,” were often quoted by Democrat President Franklin Roosevelt in promoting his socialistic “New Deal” programs in the 1930s.

Much of Marx’s praise of Lincoln, however, was based on the communist founder’s equating of the abolition of slavery in the American South with his dream of a worldwide revolution by the working-class masses. In doing so, Marx also mistakingly portrayed Lincoln as the leading proponent of abolition and even compared him to the radical abolitionist John Brown. This idea was expressed by Marx following Lincoln’s election to a second term in 1864. In a letter of congratulations to Lincoln on behalf of the newly formed IWA, the First International of the Workingman’s Association in London, Marx said, “If resistance to the Slave Power was the reserved watchword of your first election, the triumphant war cry of your re-election is Death to Slavery.”

Marx’s letter also repeated his opinion that the conflict was only about slavery by adding that “as the American War of Independence initiated a new era of ascendancy for the middle class, so the American Antislavery War will do for the working classes.” Marx ended the letter by saying that Lincoln was responsible “for the rescue of an enslaved race and the reconstruction of a social world.” Marx later amplified such thoughts by saying that Lincoln’s actions in freeing the slaves “sounded the tocsin for the liberation of the world’s working class.”

Shortly after the war in America had ended, the IWA was joined by a number of other communist, socialist and anarchist groups, as well as Marxist trade unions, from throughout Europe and had as many as eight million members. Then, in 1872, various factions of the IWA moved their headquarters to New York City and two years later, the group united with socialist organizations in New Jersey and Pennsylvania to form America’s first Marxist political party, the Social-Democratic Party of North America.

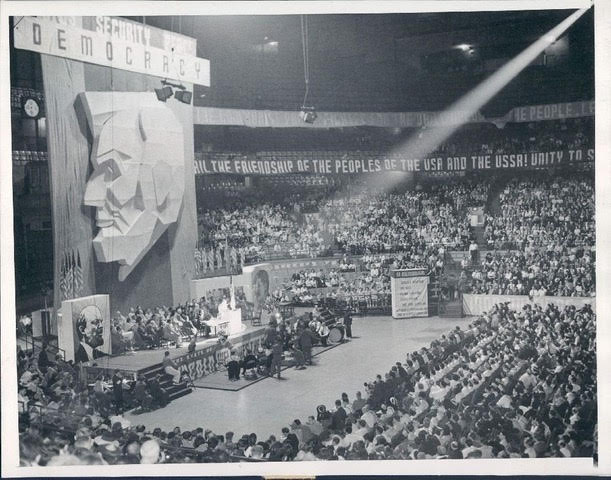

Inspired by Lenin’s bolshevik revolution in Russia at the end of the first World War, the Communist Party of the United States was formed in Chicago in 1919. Lincoln was certainly not forgotten though, and the new party soon began holding Lincoln-Lenin rallies every February. At one 1939 communist rally in Chicago to mark the party’s twentieth anniversary, a gargantuan image of Lincoln was displayed that dwarfed the smaller pictures of Lenin and Stalin. Furthermore, when the Third Communist International in Moscow raised troops worldwide in 1936 to fight for the socialist government in Spain, one three-thousand man unit from the United States was named the “Abraham Lincoln Brigade.”

Perhaps one of the best examples of Lincoln’s adoration by the communists can be found in a speech given in Springfield, Illinois, on February 12, 1936, by Earl Browder, the secretary general of the American Communist Party. In his address, Browder compared the problems that were being faced in America at that time with those with which the country had to deal in the mid-Nineteenth Century. He also said that in order to resolve the problems of the present day, Lincoln’s acts to bring about labor and social reform should now be followed by a new party made up of communists, socialists, labor unions, farmer’s associations and the half-million members of the Townsend Plan clubs . . . the forerunner of America’s Social Security system.

Browder also stated that not only Marx had high regard for Lincoln, but so did Lenin and quoted a 1918 letter to the American workers in which the bolshevik leader praised Lincoln for his leading role in, what Lenin termed, “the revolutionary and progressive significance of the American civil war,” Browder then added that “revolution is the essence of Lincoln’s teachings.”

In his closing remarks, Browder cited a passage from Lincoln’s first inaugural address on March 4, 1861, in which the incoming president stated, “This country, with its institutions, belongs to the people who inhabit it. Whenever they shall grow weary of the existing Government, they can exercise their constitutional right of amending it or their revolutionary right to dismember or overthrow it.”

While such words by Lincoln tended to coincide with the revolutionary dogma of the Communist Party, it is ironic that they also were uttered two months after seven Southern states had already acted on what Lincoln termed their “constitutional right,” and departed from the Union to form a more acceptable government. Furthermore, Lincoln’s inaugural rhetoric would also seem to validate the South exercising its “revolutionary right to dismember” the government of which it had grown weary.

Nevertheless, completely ignoring what he had said just a month earlier, as well as his pledge to the South in the same address that “the government will not assail you,” Lincoln chose to regard the seven Southern state’s peaceful acts of secession as violent acts of insurrection and prepared the nation for a war to quell what he claimed was their rebellion. His calling for troops to invade the departed states, rather than unifying the country for such an effort, caused four additional Southern states to leave the Union and join the Confederacy.

Over the past several decades, presentism has become increasingly pervasive in historiography, and this is particularly true in relation to the events which took place during America’s antebellum period. What led to the secession of the Southern states and what caused the North’s rush into war to prevent their departure is now seen only through the lens of slavery.

The mistaken concept that the War of Secession was fought only to free the Southern slaves is not a modern one, however, as the father of communism, Karl Marx, viewed the events of his day as little more than a revolutionary struggle between the world’s laboring masses and their capitalist overlords. In this, Marx also considered American slavery as part of that struggle and thus proclaimed the Lincoln-led crusade to be the “American Antislavery War.”

On the lesser point of the Germans who immigrated to join the Union army, I once read a biography of Seward which said that American consulates all over Europe actively tried to recruit immigrants to come and join the army.

Would it be unreasonable to call them “Lincoln’s Hessians”?

No. But then those who deny Lincoln’s crimes, also deny reason.

I think William Marvel touches on that subject in his book, “Lincoln’s Mercenaries,” though my memory may be faulty there. A good examination of the role German 48’ers played in the Republican Party and Lincoln’s War is the book “Lincoln’s Marxists” by Al Benson Jr., and Walter Donald Kennedy.

Thanks for the tip about LINCOLN’S MERCENARIES. I read Marvel’s MR. LINCOLN GOES TO WAR a number of years ago.

Excellent book !

I have the read the original Red Republicans and Lincoln’s Marxists too !

Just bought the most recent version Lincoln, Marx and the G.O.P. But I haven’t had the chance to read it yet.

Great topic! I’m always amazed at how much history has been ignored, oversimplified, and distorted. I am just getting into the Kennedy/Benson book “Red Republicans and Lincoln’s Marxist”. I appreciate that we have historians willing to do the research it takes to see the bigger picture.

………..Nevertheless, completely ignoring what he had said just a month earlier, as well as his pledge to the South in the same address that “the government will not assail you,” Lincoln chose to regard the seven Southern state’s peaceful acts of secession as violent acts of insurrection and prepared the nation for a war to quell what he claimed was their rebellion……….the more i read lincolns stuff the more and more it seems he “completely ignores” what he would say just weeks earlier to a different audience.

and with marx in London at the time i wonder how much he was used by British wealth, nobility, etc. to unseat the repbulic.

Dishonest Abe Lincoln may not have been a Communist in name but the traitor was certainly a Communist at heart.

This is a subject I have written about for going on 30 years now. If you can, get a copy of Walter Kennedy’s and my book “Red Republicans and Lincoln’s Marxists” published by iUniverse back in 2007. A ore recent edition of it is “Lincoln’s Marxists” published by Pelican Publishing but that edition is out of print now, though you might find some used copies for sale. I have had numerous articles on my blog https://revisedhistory.wordpress.com in the last 10 years about Lncoln and his affinity for Marxism.

Really enjoyed your comments about, Lincoln and Marx. Just a note that a gentleman whom I recall had much information about this in his series called, ” The Coperhead Cronical”. I remember he had documents showing that Lincoln and Marx were pen pals. He also said they never met formally. These things must be told and known.

Excellent article. I highly recommend the book “Red Republicans and Lincoln’s Marxists”, by Al Benson, Jr. and Walter Kennedy which goes into detail concerning the socialist criminals who came to America and joined Lincoln’s army of terrorists.

A good way to compare Lincoln and Marx is to go beyond Marx and consider what might be called pure radicalism. Pure radicalism goes like this. The world is controlled by the ruling class. These people run things for their own benefit at the expense of the rest of the population. The whole world is a great concentration camp in which the lower classes are held in a state of poverty, ignorance and back-breaking labor so that the ruling class can live in luxury and idleness. But how is this done? All radicals say that the people are oppressed by a certain institution, but they cannot agree on what this institution is. Radicalism then breaks up into sects according to which institution must be abolished to liberate the toiling masses. Some say capitalism. Others say slavery or serfdom or segregation or monarchy or aristocracy or imperialism or the state or the church or something else. Note that slavery and capitalism do not ultimately matter. What matters is that the people are oppressed and that they can be liberated by abolishing something, whatever it may be.

The idea of class oppression does seem to be part of the truth. The main problem is that from the dawn of civilization until very recently nearly all societies have been hereditary aristocracies. Class distinctions must be performing some necessary service, or there must be something that makes oppression unavoidable. The other problem is that attempts to free the lower class often lead to anarchy, tyranny and war. Lincoln, Stalin, Mao, Robespierre and all the rest are examples of reformers whose method of reform led to disaster.

I have a series of articles about who was really responsible for Lincoln’ assassination on my substack pages https://albensonjr.substack.com which goes against the prevailing fairy tales we’ve been told about who killed him. It was not the South. It was people in his own government and radical Republican abolitionists.