Who has not heard of Wounded Knee? Most know at least the general facts surrounding what is acknowledged as an atrocity committed by the army of the United States. On December 29th, 1890, the 7th Cavalry surrounded a band of Ghost Dancers—a spiritual movement of the Lakota Sioux—near Wounded Knee Creek. The soldiers demanded that the Indians surrender their weapons. As the Indians made to comply, a fight broke out between an Indian and a soldier and a shot was fired. When it was over, it is estimated that between 150 to 300 Indians—nearly half of whom were women and children— had been killed; the cavalry lost 25 men. Wounded Knee is considered the last major confrontation in the deadly war of extermination waged by the American government against the Plains Indians.

But Wounded Knee was also a fitting footnote to the tactics of the United States military that began some thirty years earlier when it was loosed not against the Plains Indians but against people with whom that military shared a common heritage of struggle and liberation from the tyranny of Great Britain. Despite growing ill-feeling between the sections which only deepened as the 19th century progressed, the United States still taught the principles of civilized and just warfare as codified by Hugo Grotius and Emmerich de Vattel. Indeed, Lincoln’s lead general Henry Halleck wrote General Order 12 declaring that assaults on civilians were: “coming into general disuse among the most civilized nations.”

Yet, the first strategy created by General Winfield Scott at Lincoln’s request and utilized from the commencement of the war targeted non-combatants. The Anaconda plan was created to starve the South into submission, depriving her people not just of arms and munitions, but food and medicine, the essentials of life itself. Thus, the nature of the war that was to be waged against the people of the South was in place from the beginning. All that happened afterward was simply the extension and exacerbation of the already chosen path of total war against every man, woman and child of the Confederacy.

Much has been made of Lincoln’s General Order 100, also known as the Lieber Code. Most of those who have commented have bestowed upon Lincoln the mantle of the first man to create an “extraordinary code that emerged … to change the course of world history.” And that Lincoln’s Code is the … inspiring story of . the idea that conduct in war can be regulated by law.” But these votaries forget that prior to Lieber there were the codes of Grotius and deVattel that had been taught at West Point and other such institutions and these codes forbade assaults by armies upon noncombatants. Lieber, on the other hand, gave Lincoln what he wanted—something that sounded good but allowed him to murder, plunder and pillage under the concept of “military necessity!” Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon recognized—and denounced—this cunning duplicity, stating that:

“…a commander under this code may pursue a line of conduct in accordance with principles of justice, faith, and honor, or he may justify conduct correspondent with the barbarous hordes who overran the Roman Empire…”

Indeed, despite its pretense of “civilized conflict” Lieber openly endorsed the concept of “hard war” by defining it as a struggle not limited to armies and navies. Remember Halleck’s observation that assaults on non-combatants were “coming into general disuse among the most civilized nations.” Are we then to assume that Lieber’s code was written for a nation that was not “civilized?” In Article 21, Lieber states: “The citizen . of a hostile country is thus an enemy.and as such is subjected to the hardships of war.” Article 29 states, “The more vigorously wars are pursued, the better it is for humanity.” One has to wonder how Lieber defined “better” and “humanity.” Finally, he concludes, “The ultimate object of all modern war is a renewed state of peace.” Well, there is nothing more peaceful than the grave.

In Lieber’s code, necessity always trumped both legality and humanity. Sherman and Sheridan would never have undertaken their atrocities had they followed any of the codes of war taught at the Point under Halleck. Indeed, on August 4, 1863, Sherman wrote to Grant at Vicksburg,

“The amount of burning, stealing and plundering done by our army makes me ashamed of it. I would rather quit the service if I could, because I fear that we are drifting to the worst sort of vandalism …You and I and every commander must go through the war, justly charged with crimes at which we blush.”

However, in a later response to a Southerner who called him a barbarian, Sherman said that he, as a commander:

“may take your house, your fields, your everything, and turn you out helpless to starve. It may be wrong, but that don’t alter the case.”

Author Otto Eisenschiml, writing less than 20 years after the Nuremberg war crimes trials, asserted that Sherman should have been hanged just as the Nazi war criminals had been hanged! Instead, he was lauded, honored and promoted by a grateful government.

Of course, there were federal officers who objected. Robert Gould Shaw, the commander of the famous black regiment honored in the film Glory, was commanded by a superior officer to burn Darien, Georgia. Shaw later wrote to his wife:

“for myself, I have gone through the war so far without dishonor, and I do not like to degenerate into a plunderer and robber—and the same applies to every officer in my regiment.”

Union hero, Joshua Chamberlain, wrote to his sister on December 14th, 1864, after having burned the homes of women and children near Petersburg, Virginia at Grant’s order:

“I am willing to fight men in arms, but not babes in arms.”

Union General Don Carlos Buell resigned in protest, writing:

“I believe that the policy and means with which the war was being prosecuted were discreditable to the nation and a stain on civilization.”

Even Northern newspapers commented upon such atrocities. One New York paper, referring to Sherman’s “capture” and deportation of 400 young women with their children from Rosewell, Georgia cried:

“…it is hardly conceivable that an officer bearing a United States commission of Major General should have so far forgotten the commonest dictates of decency and humanity… as to drive four hundred penniless girls hundreds of miles away from their homes and friends to seek their livelihood amid strange and hostile people. We repeat our earnest hope that further information may redeem the name of General Sherman and our own from this frightful disgrace.”

Many of the women were raped by their soldier captors during their journey to Marietta after which they and their children were imprisoned, starved, mistreated and then sent North without subsistence. Not one of these poor unfortunates ever returned home after the war, an act more savage than Wounded Knee.

Indeed, distinguished military historian B. H. Liddell observed that the code of civilized warfare which had ruled Europe for over two hundred years was first broken by Lincoln’s policy of directing the destruction of civilian life in the South. On this matter, Liddell wrote “This policy was in many ways the prototype of modern total war.”

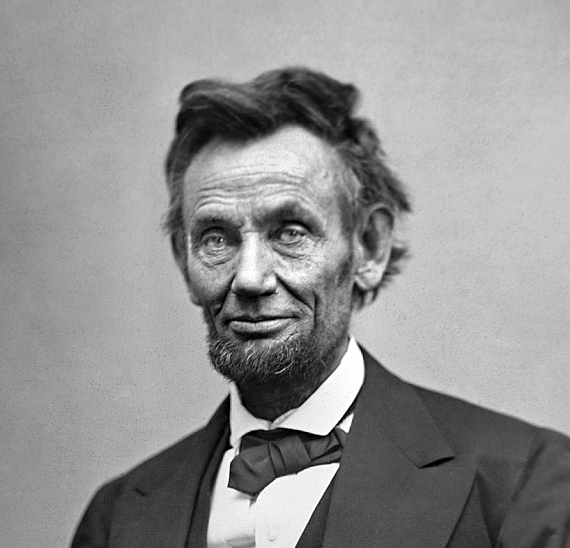

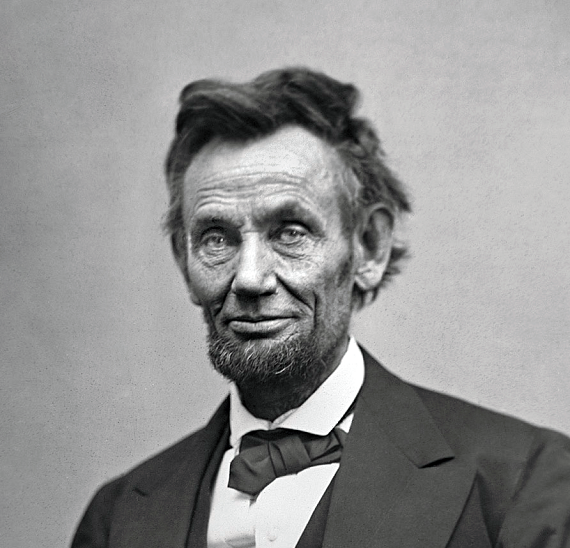

Neither was Lincoln ignorant of his armies’ atrocities. In his memoirs Sherman wrote that at a meeting with Lincoln after his March, the President was eager to hear the stories of how thousands of Southern civilians, mostly women, children, old men and slaves, were plundered, tortured, raped, murdered and rendered homeless. According to Sherman, the President laughed almost uncontrollably at these narratives. Sherman’s biographer Lee Kennett, concluded that had the Confederates won the war, they would have been:

“justified in stringing up President Lincoln and the entire Union high command for violations of the laws of war, specifically for waging war against noncombatants.”

It had always been Lincoln’s strategy not only to defeat the South but to destroy both the culture and the will of the people by targeting civilians. Under the concept of “military necessity,” Lincoln’s new code of war allowed him to do whatever was required to achieve that end and his commanders followed suit. Even General Halleck author of General Order 12, abandoned his concern for civilization. Ulysses Grant decided after the Battle of Shiloh in April of 1862, that the only strategy possible was to annihilate the South. Writing to Sheridan and Sherman, Grant stated,

“We are not only fighting hostile armies, but a hostile people and we must make old and young, rich and poor feel the hard hand of war.”

Contrast this strategy with Robert E. Lee’s General Order 73 issued during his campaign into Pennsylvania:

The commanding general considers that no greater disgrace could befall the army, and through it our whole people, than the perpetration of the barbarous outrages upon the unarmed, and defenseless and the wanton destruction of private property that have marked the course of the enemy in our own country. Such proceedings not only degrade the perpetrators and all connected with them, but are subversive of the discipline and efficiency of the army, and destructive of the ends of our present movement.

It must be remembered that we make war only upon armed men, and that we cannot take vengeance for the wrongs our people have suffered without lowering ourselves in the eyes of all whose abhorrence has been excited by the atrocities of our enemies, and offending against Him to whom vengeance belongeth, without whose favor and support our efforts must all prove in vain.

The commanding general therefore earnestly exhorts the troops to abstain with most scrupulous care from unnecessary or wanton injury to private property, and he enjoins upon all officers to arrest and bring to summary punishment all who shall in any way offend against the orders on this subject.”

Now, a point must be made here. Lee is acting according to the God of Scripture to whom he refers as “…Him to whom vengeance belongeth…” Grant and the federal commanders—along with Lincoln— were obeying the will of their god, the almighty national government. As the war developed, this religious dichotomy redounded badly to the Confederacy. In England, Confederate agent and procurer of warships, James Bulloch had built such ships as could bombard Northern cities from the sea—but their use was rejected by the Confederate government as uncivilized and barbaric.

The simple fact is this: while the North sought to occupy the land and obliterate the culture and will of the people of the South, the South—whose military commanders were steeped in military tradition based on Christianity, humanitarianism and Western civilization—did not seek to foist its cultural and social values on the North, neither did they wish to rule it. They sought only to leave it. When all was lost and Gen. E. Porter Alexander recommended that the Confederate armies take to the hills and wage guerrilla warfare against their wicked conquerors, Lee opposed the idea. Author Jay Winik in his book “April 1865” wrote of Lee:

“Lee was principled to the bitter end.. .thinking not about personal glory, but…What is honorable? What is proper? What is right? … he quickly reasoned that a guerrilla war would make a wasteland of all he loved.even if it worked, and perhaps especially if it worked.For Lee that was too high a price to pay. No matter how much he loved the Cause.there were limits to Southern independence.”

However, there were no limits recognized by Lincoln and his forces as to what could and should be committed and sacrificed to the mythical concept of a “perpetual sacred Union.”

The treatment of both civilians and Southern cities were reminiscent of ancient wars long before men such as Grotius, de Vattel and even Lieber wrote their codes. The US army expelled civilians from their homes in retaliation for their forces being fired upon. They burned cities and left them in ruins. They executed civilians in retaliation for attacks of which they knew the civilians involved to be innocent— expressly forbidden by Lieber Code paragraph 44 and Paragraph 148 which forbids the proclamation of infamy on civilians, declaring that, “The sternest retaliation should follow the murder committed in consequence of such proclamation made by whatever authority.” Gen. Eleazer A. Paine committed such murders and was reputed to have hanged so many uniformed Confederate prisoners that he was nicknamed “the Hanging General.” Yet, Paine was never brought to book for his crimes.

During his masterpiece of atrocity, the infamous March to the Sea, Sherman wrote to Halleck in 1863, a masterpiece of the rationale of Total War:

“If we can, our numerical majority has both the natural and constitutional right to govern. If we cannot whip them, they contend for the natural right to select their own government.”

In effect, Sherman speaks here of might giving the Union the right to force Southerners to accept a government—or more precisely, a god—they had rejected. But the right to select one’s government was exactly what the Declaration of Independence—and all that followed—was about! However, to ensure that the South would be prevented from exercising this right of free men for which both North and South fought in the Revolutionary War, Sherman would, in his own words, “remove and destroy every obstacle, take every life, every acre of land, every particle of property, everything that to us seems proper.” (Official Records Series 1, Vo. 30 part 3).

The Lincoln myth of a gentle and compassionate man who, in his own words, “had no desire to take bloody vengeance” on the people of the South or to kill or subjugate them or confiscate their property or to deprive them of their legal and constitutional rights is both absurd and a lie. After issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln stated,

“the character of the war will be changed. It will be one of subjugation.. .the South is to be destroyed and replaced by new propositions and ideas.”

Lincoln’s policies eradicated not only the South, but the concept of a Federal Union as laid down by the Founding Fathers in the Constitution.

Then there are the crimes committed against Southern prisoners of war. In 1903, Adj. Gen. F. C. Ainsworth estimated that more than 30,000 Union and 26,000 Confederates died in captivity (that is 12% died in the North and 15.5% died in the South). However, the numbers and the death rate of Confederate prisoners were vastly understated first, because many captives died without their deaths being recorded and secondly, the winners did not wish to admit to the hideous rate with which those in at their mercy perished. Indeed, Rhodes admitted that there should have been a much greater disparity— even using his own numbers—in favor of survival for those imprisoned in the North, given the superior conditions existing in the North. But the simple fact is this: from the beginning of the War, the federal government intended to “make treason odious” by treating captured Confederate soldiers as traitors and rebels rather than legitimate prisoners of war.

Even the usually chivalrous George McClellan forced Confederate prisoners to clear mine fields after some of his men were killed despite the fact that such usage of prisoners was expressly forbidden by the Lieber Code in paragraph 75. Sherman added his own perverse twist to this practice when he used civilians as well as prisoners for this purpose. Prisoners were routinely tortured mutilated and killed in Northern hell-holes called “camps.” Confederate officers were used as human shields in the famous instance of the Immortal 600 and the morality rate from torture, starvation, exposure and disease in Federal prison camps was astonishing. Elmira prison in New York had a 24% death rate, higher than any other prison on either side including the infamous Andersonville.

As for Andersonville: yes, there were war crimes, but they were not committed by either the Confederate government or camp commander, Col. Henry Wirz. The crimes were committed by Ulysses S. Grant and Abraham Lincoln. On August 19th, 1864, Grant wrote to Union Secretary of State Seward:

“We ought not to make a single exchange nor release a prisoner on any pretext whatever until the war closes.”

Now the exchange problem between the two sides—hampered by former slaves found fighting for the Union—was by no means all the fault of the Union. But in Andersonville, there was a much greater crime than the problem of exchange. The South, starving and destitute, could not feed or care for its own people much less its prisoners. The greatest problem lay in Andersonville where the prisoners ate the same food as their guards—and in the same amount—but that was not sufficient, neither was there enough medicine to care for those who became ill.

Col. Robert Ould, who had been in charge of prisoner exchanges since the beginning of the war, wrote about the situation in Andersonville to his Union counterpart Gen. Mulford. Ould recites the efforts made by the Confederate government to succor the federal prisoners even after prisoner exchange had ended.

“My government instructs me to waive all formalities and what it considers some of the equities in this matter of exchange. I need not try to conceal from you that we cannot feed and provide for the prisoners in our hands. We cannot half feed or clothe them. You have closed our ports till we cannot get medical stores for them. You will not send us quinine and other needed medicines, even for their exclusive use. They are suffering greatly and the mortality is excessive. I tell you all this plainly, and still you refuse to exchange. What does your government demand? Name your own conditions and I will show you my authority to accept them. You are silent! Great God!, can it be that your people are monsters? If you will not exchange, I will give you your men for nothing. I will deliver ten thousand Union prisoners at Wilmington any day that you will receive them. I will deliver five thousand here on the same terms. Come and get them. If your government is so damnably dishonest to want them for nothing, you shall have them. You can at least feed them and we cannot. You can give us what you please in return for them.”

Was there a war crime at Andersonville? Yes! Upon the cessation of exchange, the Confederate government asked for medicine for the exclusive use of the imprisoned federal soldiers and were ignored! The anguish, frustration and bitterness of Ould are voiced in the sentence: “Great God! can it be that your people are monsters?!” The answer to that was, “yes.” Their own men were considered expendable in this campaign of genocide. Edward Wellington Boate was a soldier in the 42nd New York Infantry and a prisoner at Andersonville in 1864. He wrote of his experiences in the New York Times shortly after the war and commented on whom he held responsible for Andersonville’s legacy:

“You rulers who make the charge that the rebels intentionally killed off our men, when I can honestly swear they were doing everything in their power to sustain us, do not lay this flattering unction to your souls. You abandoned your brave men in the hour of their cruelest need. They fought for the Union and you reached no hand out to save the old faithful, loyal and devoted servants of the country. You may try to shift the blame from your own shoulders, but posterity will saddle the responsibility where it justly belongs.”

When some of the Andersonville prisoners were returned to the North without exchange, these poor animated skeletons were taken, photographed and used to generate hatred in the North for what were condemned as the evil, wicked, brutal people of the South. Shortly after the photographs were released, the United States Senate passed the following:

PREAMBLE TO HOUSE RESOLUTION #97 Also known as the Retaliatory Orders

“Rebel prisoners in our hands are to be subjected to a treatment finding its parallels only in the conduct of savage tribes and resulting in the death of multitudes by the slow but designed process of starvation and by mortal diseases occasioned by insufficient and unhealthy food and wanton exposure of their persons to the inclemency of the weather.” … passed by both houses, January 1865.

Of course, this very policy had been ongoing in most of the federal prisoner of war camps since the beginning of the war. The Andersonville photographs merely gave an excuse for a policy of long standing.

Interestingly enough, in this litany of atrocities committed against non-combatants and helpless prisoners, one of the groups to suffer most both during and after the war were the very people for whom, if one believes today’s rhetoric, the war was fought—the slaves. Sherman exhibited a virulent hatred of blacks. He believed them “obstacles to the upward sweep of history, wealth and White destiny—and he felt the same way about the Indian, a situation that eventually led to “incidents” such as Wounded Knee. Lincoln’s opinion of blacks is, of course, well known. When Lincoln met with Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens just before the end of the war, Stephens asked Lincoln what would happen to the former slaves—some three million—cast adrift in a desolated South and not permitted to migrate north. To this Lincoln smiled and repeated an old minstrel show line that they would have to “…root, hog or die.” What Lincoln meant by this was that it would be a matter of the survival of the fittest. Sadly, a great many former slaves—especially the very young and the very old—found freedom to be fatal.

The atrocities committed against the People of the South, military and civilian, men and women, white and black, slave and free, young and old, well and ill, sound and wounded are on such a vast scale that they cannot be comprehended, much less revealed in a small article. There are books on the subject such as Dr. Brian Cisco’s War Crimes Against Southern Civilians, but there are also writings suggesting that, in effect, the South had it coming. Given that the people of the South wished only to leave the Union without violence, and that the institution of slavery in those states was not unique to the region, neither was the South involved in the slave trade—that was a Yankee enterprise—it would seem that such horrific treatment of a people whom Lincoln declared to be Americans, citizens of his sacred Union is inexplicable.

But holy wars are vicious. The enemy is not a man or a woman or a child or a neighbor or a brother— but an apostate, a blasphemer, an infidel—and as such, is worthy of no less than death—and even annihilation! That is why Lincoln, his government and his military waged bloody jihad from April of 1861 to April of 1865. Had the war gone on longer, the people of the South might well have been reduced to the conditions of the Cheyenne, the Apache and the Lakota Sioux. Certainly, Generals Sherman and Sheridan and their leader Abraham Lincoln would have shed no tears for their plight.

Conclusion

Let us look at what we have learned. The need to have a proper understanding of what is commonly, but erroneously referred to as the Civil War has a direct relationship to critical issues facing us today. Americans are used to thinking that upon the ratification of the Constitution, our Republic was established and has remained inviolate since that time; that it was “saved” by Abraham Lincoln in a victorious war waged by the noble and patriotic Union over the traitorous and wicked slave-masters of the South. But we must remember that the war not only ended the South’s attempt at secession—a right guaranteed under that same Constitution—but also in large part, ended the Republic as it was set up under that Constitution by the Founders. For the Republic of 1789 was, for all intents and purposes, the first of many American nations. In 1865, the victory of the national government over the States—and not just the Southern States!—in the Civil War initiated a series of subsequent “virtual nations,” each with a central government more powerful than the one that preceded it. Let us trace this evolutionary path:

1779: The power of the Sovereign States is supreme; these are individual nations as admitted in the Treaty of Paris; the new nation governs through the Articles, first of Association and then of Confederation indicating a growing desire to work towards a perfection of their not yet completed union.

1789: The power of the States dominates but a Federal Government outside of the States is created by the Constitution, a compact that replaces the Articles. This government has enumerated and limited powers in order to address those situations beyond the scope of individual States even acting in concert.

1861: With the States (and culture) of the South confined within its original geographic borders, the power of the rest of the Union has grown to the point at which these States are able to force their will on the Southern States, using the income generated in those States to succor and support the rest. American manufacturing is supported by monies raised by high tariffs that hurt most of all the agricultural South without any compensation to those States. This situation was defined by Missouri Senator Thomas H. Benton in 1828—three decades before the Cotton States acted to escape political and financial servitude. Speaking on the floor of the Senate Benton stated:

“Before the (American) revolution [the South] was the seat of wealth … Wealth has fled from the South and settled in regions north of the Potomac: and this in the face of the fact, that the South … has exported produce, since the Revolution, to the value of eight hundred millions of dollars; and the North has exported comparatively nothing. Such an export would indicate unparalleled wealth, but what is the fact? … Under Federal legislation, the exports of the South have been the basis of the Federal revenue …Virginia, the two Carolinas, and Georgia, may be said to defray three-fourths of the annual expense of supporting the Federal Government; and of this great sum, annually furnished by them, nothing or next to nothing is returned to them, in the shape of Government expenditures. That expenditure flows northwardly, in one uniform, uninterrupted, and perennial stream. This is the reason why wealth disappears from the South and rises up in the North. Federal legislation does all this!”

1865: The Federal Government triumphs in war over those States wishing to exercise what had been recognized as their rights under the Constitution to leave the original union and form a new one of their own choosing. This military victory carried forth in the name of that government – Lincoln never spoke of the Union, but of the “government” – overturns the Constitution of 1789 and replaces it with a “constitutional understanding” in which the Federal Government is dominant over all the States and not just those it had defeated in war. This situation reflects the new reality begun decades before the War involving an alliance of commerce with the expanded coercive power of the central government in order to facilitate their respective agendas: profit and power.

1933: The power of the Central Government is now invulnerable; the States serve as mere counties able to exercise power only at the local level. The “emergencies” of World War I, the Great Depression and the Second World War further strengthen its power, permitting programs such as the New Deal and other direct intrusions into the lives of the People over which the States have neither control nor influence.

1965: The power of the National Government is now absolute; what little power remains to the States is further marginalized. Federal affiliation with the civil rights movement and social programs such as the Great Society solidify central power while further reducing what small powers had remained in the States. More and more formerly state matters—such as crime—are removed from local and State purview to federal control. Less than ten years later, the Supreme Court strikes down all State legislation rulings on abortion by declaring the killing of children in the womb a “constitutional right.” All efforts to affect this finding by the States or the People are dismissed out of hand. Also at this point, large lobbying groups in both the public and private sectors wield more power at the federal level than do the formerly sovereign States much less the People.

2008: The Federal System, long existing in name only is finally abandoned. Both the States and the People are powerless in the grip of a government that no longer recognizes even a remnant of the Constitution and the Founding Principles. Still, many Americans continue to believe that the Republic still exists and in the name of Washington, Jefferson and the Constitution they work to influence a situation that has deteriorated to the point at which the establishment of an actual police state seems not a question of “if,” but of “when.”

2021: Today there is an ongoing powerful and ubiquitous effort to finally, once and for all, consign to oblivion the ideas and ideals that drove the People of the South to secede from a union they considered antithetical to the well-being of their people—ideas and ideals which they continue to boldly declare through the use of Confederate symbols, monuments and memorials. The fact that their cause is all but lost can be seen in the ongoing successful war against those same monuments and symbols.

Supporters of this crusade against the South—for this remains a religious war—declare that the killing of hundreds of thousands—perhaps as many as a million—Americans and the destruction of a people in the so-called Civil War was justified to end slavery, a claim that is demonstrably false. But even those who care nothing about the war, its origins or its meaning, revere Lincoln as a hero and a Savior of the nation. He was, we are endlessly told, America’s greatest President. Indeed, Lincoln’s monument is a temple fit for worship rather than a mere memorial. But those who justify Lincoln and what was done in the War of Secession with the plea that “it was necessary”—for whatever reason—justify every tyrant in history who has raped, pillaged, enslaved and slaughtered his way into power as well as every one who will rise in the future.

Embracing the motive for tyranny neither changes its moral dynamics nor its consequences. If we permit the final extermination of Southern heritage and the memory of those boys in gray who fought and died for their homes and their God-given liberties, we consign not just the South, but America, that great experiment, to oblivion.

Thank you, Ms Protopapas for a wonderfully well written essay on a truly horrific subject. The old aphorism that “the victors write the history books” has never been more completely illustrated than in the current officially told lies about the War Between the States. I managed to raise my son with an understanding of the truth, but you have managed to write an article which (God willing!) may educate thousands. Good job!

The war started when the north attacked Ft Sumpter was over “states rights”, not slavery. Lincoln, Sherman and Grant were, by all accounts, absolute monsters where human rights and race were concerned. The so-called Emancipation Proclamation was merely a political tool to disrupt the under-resourced south. This, of course, was at the expense os the negro. The slave trade had already been halted before the war. Lee and Davis were in fear on the industrial slavery of the north which allowed no rights, human dignity, or hope of individual economic or social ascent. It is dreamy to contemplate the astounding heights the civilization of the south would have reached if not for Lincoln’s war. Republicans destroy all !!!

I live in eastern Pennsylvania and am appalled at the ignorance of northern civil war buffs. They tell me that the southern civilians got what they deserved. What? Rape and murder and stealing are ok? Lincoln and his generals should be exposed for their war crimes, not treated like heroes.