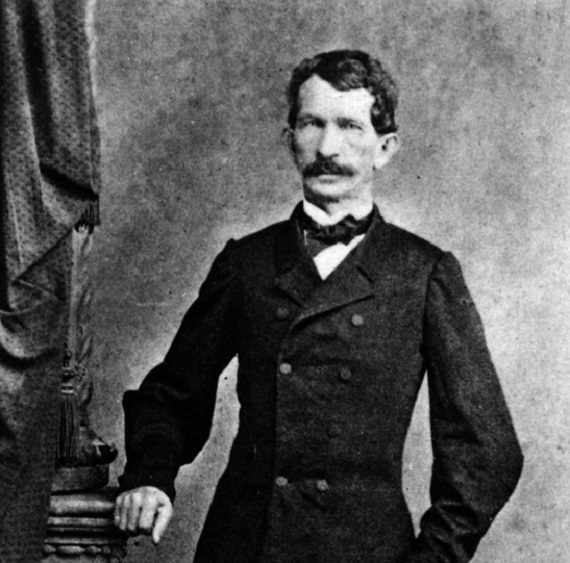

Louisiana is a state accustomed to incredibly incompetent and corrupt public officials, especially in the governor’s office. Some of my fellow Louisianans will be surprised to know that one of their former chief executives was a model of competence, ability, courage, and self-sacrifice. One Pulitzer Prize-winning historian even suggested that, had the South recognized his talents earlier, the results of the War for Southern Independence might have been different.

Henry Watkins Allen was born on April 29, 1820, in Farmville, Prince Edward County, Virginia, the son of Dr. Thomas Allen, M.D. and Ann Allen, nee Watkins. After his wife died in 1830, Dr. Allen moved his family to Missouri.[1] Henry was educated at local schools in Philadelphia, Missouri, worked as a store clerk, and attended Marion College in Philadelphia for two years. He ran away from home at age 17 and became a tutor on a plantation in Grand Gulf, Mississippi, and studied law at night. He gained admission to the Mississippi bar in 1841.

Henry Allen possessed an adventuresome nature and abundant energy. He joined the Army of the Republic of Texas in 1842 when it appeared that war with Mexico was imminent, and he rose from private to captain in six months. After the war did not materialize, Allen returned to Mississippi, where he married Salome Crane of Rodney, Mississippi, in 1844. She was beautiful but her health was fragile, and she died in 1851 at age 26 or 27. They had no children. Meanwhile, Henry acquired a plantation in Tensas Parish, Louisiana, and raised several cotton crops.

Allen was elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives in 1845 and served until 1847. Following his wife’s death, he acquired “Allendale,” a large sugar cane plantation in West Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana, became wealthy, owned 125 slaves, and built his own railroad, which headquartered at what is now Port Allen, Louisiana, across the Mississippi River from Baton Rouge. Allen was elected to the Louisiana legislature in 1853 but lost a bid for the state Senate in 1855. Meanwhile, he journeyed throughout the South and wrote letters describing his travels. The Baton Rouge Comet published his work under the pseudonym Guy Mannering.[2] He went north in 1854 and studied law at Harvard for a year.

Henry Allen traveled to Europe in 1859. He intended to take part in the Italian revolution, but it was over when he got there, so he toured the continent and wrote a book, Travels of a Sugar Planter, about his adventures and observations. He was re-elected to the legislature while overseas. When he returned, Allen became a floor leader for the Democratic Party. With war clouds forming on the horizon, he enlisted in the Delta Rifle Company as a private in 1860.

In 1861, Allen founded the Louisiana Historical Society and served as its first president. He also took part in the seizure of the Federal arsenal in Baton Rouge. In the spring of 1861 he joined the 4th Louisiana Infantry Regiment, was elected its lieutenant colonel on August 15, and was promoted to colonel on March 1, 1862. After commanding the garrison on Ship Island, off the coast from Gulfport, Mississippi, he and his regiment went to northern Mississippi, where they formed part of the Albert Sidney Johnston’s army in the Battle of Shiloh. He was severely wounded on April 6, 1862, when a Yankee shot him in the cheek. Allen nevertheless took part in the (1st) Siege of Vicksburg, which lasted 67 days, in 1862. Here he commanded an ad hoc brigade, consisting of the 4th and 5th Louisiana Infantry Regiments.

Foreseeing that New Orleans would fall, Major General Mansfield Lowell had ordered three batteries of heavy guns be dismantled and sent to Vicksburg. They just arrived but were not mounted when Admiral Farragut’s Union fleet began shelling the city. Colonel Allen was given the task of mounting them. During the construction of one battery, the men came under serious gunboat fire. They stopped work and ducked. The colonel instantly became furious. He drew his revolver and roared: “Soldiers, you came here to fight; you are ordered to build this battery, and d*** me if I don’t shoot down the first of you that dodges from this work; by G*d, no soldier of mine shall dodge from his duty!” The proclamation had an “electric effect” on the men, who realized that Allen was serious about shooting them. They finished constructing the battery in record time.[3]

After Farragut abandoned the 1st Siege of Vicksburg, Major General John C. Breckinridge attempted to follow up this victory by recapturing Baton Rouge. He attacked on August 5. The Union forces narrowly avoided destruction and were saved only by their artillery. At a critical moment in the contest, Colonel Allen led a charge against the Nims Battery.[4] A cannon blast shattered both of his legs. The doctors wanted to amputate one of them, but Allen refused to allow it. Perhaps he should have allowed it. He lived in pain for the rest of his life and was never able to walk again without crutches.

Not able to perform field duty, Allen served as a military judge in John C. Pemberton’s Army of Mississippi in the spring of 1863 and was simultaneously appointed major general in the Louisiana Militia. He was injured again in June 1863, while escaping a hotel fire in Jackson. Despite his permanent handicaps, the War Department promoted him to brigadier general, C.S.A., on August 19, 1863, and ordered him to Shreveport to organize paroled prisoners of war.[5] He infiltrated through Union lines and assumed his new duties in the fall of 1863.

Meanwhile, as Louisiana Governor Thomas O. Moore’s term neared its end, Allen’s friends placed his name on the gubernatorial ballot. So highly was he thought of in the Confederate-held portions of the Bayou State that no one opposed him. He was elected in November 1863 and assumed office on January 1, 1864.

Allen never allowed his wounds to sap his energy. As soon as he was elected, he did a tour of the state and accessed its resources and its needs. He met with Confederate General Edmund Kirby Smith and arranged for the transfer of large amounts of Confederate cotton and sugar to Louisiana, in exchange for the cancellation of part of the huge national debt. He immediately opened a trade route from Louisiana across Texas to Mexico, from which he could export Louisiana cotton and sugar in exchange for medicine, clothing, coffee, pins, dry goods, flour, paper, and other necessities. (Cotton prices increased from $.06 to $1.09 during the war, which is why it was called “White Gold”). He established a plant for the manufacture of hats and another to produce shoes and still another for clothes. These went to private citizens as well as Confederate soldiers. He established a system of unified currency and state-run stores, where citizens could buy basic supplies at little cost. Refugees and those who were destitute (and there were a great many in Louisiana in 1864) received them for free. He saw to it that there was no discrimination in the distribution of supplies—whites and African Americans, soldiers and civilians, men and women, Confederate sympathizers and Jayhawkers[6] were treated just the same. He imported and distributed cotton cards (tools for combing cotton fibers), which allowed people to spin and weave cotton. Louisiana’s live-wire governor set up state medical labs to manufacture turpentine, castor oil, medicinal alcohol, carbonate of soda, and other medicines. He ordered a mineral survey of the state, in hopes that he could find resources for manufacturing. When it turned out that the mineral resources of Confederate Louisiana were poor, he purchased a major share in the ironworks in Davis County, Texas, for his state. He also established a tannery and a woolen factory.

Despite the war, the incredibly well-led and efficient state government published schoolbooks and distributed them through the police juries to the children of the state—free to those whose families could not pay for them. He set up several relief centers, which provided low-cost food, blankets, and clothing. Those who could not pay got them for free. Men and women from Texas and Arkansas came to Louisiana to obtain the help they could not receive in their home states. They were never turned away. The Missouri soldiers in Louisiana went so far as to claim Allen as their governor.[7] He even proposed freeing any slave who volunteered to serve in the Confederate Army or in the Louisiana state forces, but the legislature refused to pass this progressive bill.

Henry W. Allen was a frugal man. Today’s Governor’s Mansion (which should be called the Governor’s Palace) is three stories high, has a basement and an elevator, a 90-ton cooling system, dozens of rooms, and comprises 25,000 square feet, excluding the tennis court, the swimming pool, and the fountain area. It has an eight-acre lawn. Governor Allen’s “mansion” had three bedrooms: one for members of his staff, one for guests, and one for the governor himself. He had a living room area by a fireplace, where he met with anyone who wanted to visit him, and common people called upon him continually. Whenever possible, he saw to their needs. He always put the interest of elderly women, children, widows, orphans, and soldiers’ families above those of the rich and famous. Perhaps the wealthiest man in the state antebellum, he indulged himself in only one luxury: he drank one cup of real coffee once a day. Why, one newspaper asked, was Governor Allen so honored by his people? “Simply because he makes their good his highest objective. He protects the weak, he relieves the needy, he rewards the faithful, he, in short, exercises his every constitutional power with justice, reason and humility.”[8] A great many Louisiana children born in the years immediately after the war were named “Allen.”

Douglas Southall Freeman, who twice won the Pulitzer Prize in history, said: “Allen was the single greatest administrator produced by the Confederacy. His success in Louisiana indicates that he might have changed history . . . if his talents could have been utilized by the Confederate government on a larger scale.”[9]

In March and April 1864, Union General Nathaniel P. Banks’s Army of the Gulf tried to finish off Confederate Louisiana. Banks had 32,000 men. He was opposed by Richard Taylor’s Army of Western Louisiana, which was grew to a strength of 8,800 men. To help Taylor, Allen called out the Louisiana Militia. Since the Confederacy was already drafting all males between the ages of 17 and 50, Allen’s few hundred militiamen were older men and a few boys who were next to useless, militarily speaking. They did, however, have a notably positive impact on the morale of the regular Confederate units. “Old men shouldered their muskets and came to our assistance, to help drive back the invader,” a Texas soldier recalled. The fact that Henry Allen, a crippled war hero, led them personally, increased their respect even further. (He could not walk, but he could ride, so he commanded from horseback.) Allen and his rag-tag band touched the heart of the most hardened veteran. “No nobler men ever shouldered a musket!” one soldier cried in admiration.[10]

The Louisiana militia was present at the Battle of Mansfield on April 8, 1864. General Taylor resolved not to use them except in an extreme emergency. They were the only unit he did not commit to his main attack, but fortunately, he did not need them. Taylor routed the Northern forces, surrounded them twice, and chased them for 200 miles, all the way across Louisiana. One can only imagine how General Allen felt the next day, when he saw the six guns of the Nims Battery—one of which crippled him at Baton Rouge—all in Rebel hands. It had not only lost all of its guns, but also all of its caissons, horses, wagons, and supplies. All it had left was one rubber slicker and one blanket for every five men.[11]

Eventually, the Confederate forces east of the Mississippi were compelled to surrender. Governor Allen initially wanted to keep fighting but soon realized the cause was lost. Also, the Federal authorities declared him an outlaw, wanted dead or alive and placed a bounty on his head. He wrote a long letter to the people of the state, urging them to “submit to the inevitable” and “begin life anew.”[12] With tears pouring down his cheeks, he got into an ambulance and headed for Mexico. He ended up in Mexico City, where he established the Mexico Times, an English newspaper.

In the gubernatorial election of 1865, no former Confederates or Confederate sympathizers were allowed to vote. Henry W. Allen was not on the ballot, there was no write-in campaign for him, nor was there any organized effort of any kind to persuade people to vote for him. He nevertheless finished second.

Governor Allen died of a stomach disorder in Mexico City on April 22, 1866. He was 45 years old. The people of Louisiana still loved him, however, and some of them had his remains reinterred in New Orleans in 1876 at their own expense. In 1885, he was taken to the Old Capitol grounds in Baton Rouge and was laid to rest a third time. He is the only person in Louisiana history ever to be so honored. So far, his grave has not been desecrated by the sanctimonious hypocrites of the modern-day political left.

[1] Henry Allen had two brothers and two sisters.

[2] These letters were published in book form as The Guy Mannering Letters of Henry Watkins Allen in 1985.

[3] See Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., Vicksburg: The Bloody Siege that Turned the Tide of the Civil War (Washington, D.C.: 2018), pp. 7-14, for the details of the 1862 Siege of Vicksburg.

[4] The “Nims Battery” was the unofficial name for the 2nd Massachusetts Light Artillery Battery. It was commanded by Captain (later Colonel) Ormand F. Nims, and was considered by some to be the best battery in the Union Army.

[5] Many of the men captured when Vicksburg and Port Hudson fell were from Louisiana.

[6] The term used in Louisiana for Union sympathizers.

[7] Vincent H. Cassidy and Amos E. Simpson, Henry Watkins Allen of Louisiana (Baton Rouge: 1964), pp. 106-15. Also see John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana (Baton Rouge: 1963), for the definitive work on the war in the state.

[8] Sarah A. Dorsey, Recollections of Henry Watkins Allen (New York: 1866), p. 255.

[9] William Arceneaux, Acadian General: Alfred Mouton and the Civil War (Lafayette, Louisiana: p. 120; Charles L. Dufour, Ten Flags in the Wind: The Story of Louisiana (New York: 1967), p. 171.

[10] J. P. Blessington, The Campaign of Walker’s Texas Division (New York: 1875), p. 179; T. Michael Parrish, p. 336; Cassidy and Simpson, p. 123.

[11] Caroline E. Whitcomb, History of the Second Massachusetts Battery (Nims’ Battery) of Light Artillery, 1861-1865 (Concord, N.H.: 1912), p. 70. The battery lost so many men and was so badly damaged that it had to be disbanded.

[12] Winters, p. 426.

Dr. Mitcham, thank you for a piece of Louisiana History.