A review of Fifty Southern Writers After 1900: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. Ed. by Joseph M. Flora and Robert Bain. Greenwood Press, 1987.

A few years ago, before I had been sold upriver to Clemson, some colleagues and I were busily devising a graduate reading list for the Ph.D. program in English at the University of Southern Mississippi. (I had been assigned “American Literature Since World War II.”) When another professor walked into the room and asked what we were doing, I grandly announced: “Making the literary canon.” And, of course, that’s exactly what we were doing. Neither bestseller status nor favorable mention in the literary reviews assures an author of immortality. It is only when he passed into the university curriculum that he belongs to the ages. The fact that writers, like saints, can occasionally be bumped from the canon (a fate shared by Longfellow and Saint Patrick), only proves the awesome power wielded by the church fathers of academia. This is as true of Southern literature as of any other genre.

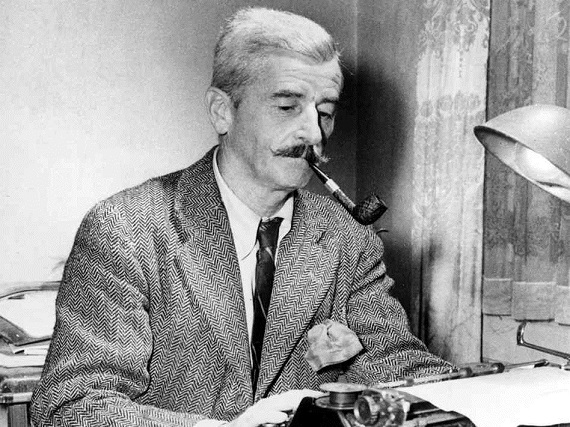

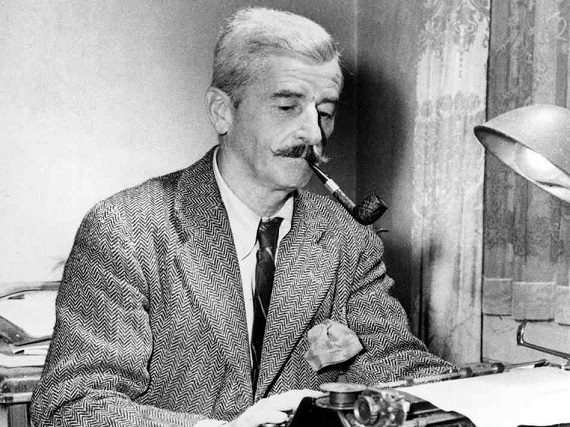

Regional differences have existed in American literature from “The History of the Dividing Line” on, and Southerners in particular have never been known to hide their light under a bushel. Nor was it any secret that from the 1920s through the 50’s, there was a creative ferment that put cities such as Nashville, Tennessee, and Oxford, Mississippi, on a literary map previously dominated by the likes of New York, London, and Concord, Massachusetts. But it was not until the publication, in 1952, of the Beatty, Young and Watkins anthology, The Literature of the South that “Southern literature” became recognized as an academic discipline in a way that, say, Midwestern literature never has been. In the ensuing thirty-five years, a consensus has begun to form concerning the

canon of Southern literature. The publication of three important books (The History of Southern Literature [1985], A Modern Southern Reader [1986], and Fifty Southern Writers Since 1900 [1987] in as many years has helped solidify that consensus.

From the standpoint of identifying the Southern canon, Flora and Bain’s Fifty Southern Writers is probably the most germane of these three books. (The History emphasizes comprehensiveness over critical discrimination, and A Modern Southern Reader, like all anthologies, features only those selections that its editors can afford to reprint–e.g. The Glass Menagerie rather than A Streetcar Named Desire.) If the figures selected by Flora and Bain are, indeed, the top fifty Southern writers of our century, it is instructive to note who was not included in their ranks. None of the writers represented in the 1922 special Southern edition of Poetry magazine has made it into the Flora and Bain canon, and only one of those included in Addison Hibbard’s 1928 anthology The Lyric South (John Crowe Ransom) has been so honored. Although a mere twenty-five modern Southern writers are featured in the most recent edition of The Literature of the South (1968), three of those (William Alexander Percy, Frank Lawrence Owsley, and Cleanth Brooks) have failed to make it into Flora and Bain’s top fifty.

What is most predictable (and to my mind, most regrettable) about Fifty Southern Writers is its preference for elitist over popular writers. Although Margaret Mitchell is included, her more problematical forerunner, Thomas Dixon, Jr., is not. Of course, Dixon’s views on race relations and the proper ordering of society are terribly unfashionable in these days of affirmative action. But what is probably more damning is his unabashed sentimentality. It was assumed during the heyday of high modernism that, in order to be serious, literature had to be ironic. Because that dictum was promulgated most energetically by Southern critics, it continues to shape the canon of modern Southern literature. Hence, when popular favorites such as Dixon and Alex Haley move millions by treating the same themes that obsessed Faulkner, their work is dismissed as mawkish and vulgar-as if indirection and obscurity were the supreme literary virtues. With the possible exception of Margaret Mitchell’s Mammy, no black character in modern Southern literature has taken possession of the popular imagination as forcefully as Dubose Heyward’s Porgy, yet neither Heyward nor any of his colleagues in the South Carolina Poetry Society warrant mention in Flora and Bain’s index, much less inclusion in their pantheon.

If one accepts the critical prejudices implied (though rarely stated) in this volume, there is much to admire in its contents. Flora and Bain have assembled a competent group of contributors, including some of the acknowledged luminaries in the field of Southern literary scholarship (Thomas Daniel Young, M.E. Bradford, Richard J. Calhoun, Virginia Spencer Carr, James H. Justus, Fred Hobson, and others). Unfortunately, the rigid format imposed upon the book does not always allow the individual critics sufficient latitude to strut their stuff. When used solely as a reference book, Fifty Southern Writers is as informative as any good encylopedia. But try reading one essay after another, and the eyes begin to glaze with the monotony of it all.

One of the problems is that the selections are arranged alphabetically. This allows no continuity from one essay to another, only eccentric pairings and odd juxtapositions. A thematic, generic, or even chronological arrangement would have made more sense but would also have made key omissions more glaring. As it is, the editors have struck a politic balance amongst various periods, genres, and sub-regions and have included a representative mixture of women, blacks, and gays. Whatever else it may be, the Southern literary canon is an equal opportunity employer.

Another important consideration in canon making is determining when one period ends and another begins. Flora and Bain have begun with the turn of the century and tried to stay up to date by including a liberal selection of living writers. As a practical matter that puts William Sydney Porter cheek-to-jowl with Reynolds Price. One might argue that the former belongs to a period earlier than what we ordinarily think of as modern Southern literature (perhaps making World War I the dividing line) and the latter to one that is later (post-Renascence, though not–thank God—postmodern). However, those who believe in the continuity of Southern literature should be grateful that Flora and Bain have not allowed an excessive veneration for the Renascence to limit their appreciation of those writers who had the historical misfortune to come before or after.

Over the past three decades or so the death of Southern literature has been proclaimed almost as frequently as the death of the novel. We are told that the Southern Renascence was a result of the conflicts produced by the assimilation of Southern culture into the mainstream of American life. Now that that assimilation is all but complete, we must look to other dying subcultures (Jews, ethnic, Catholics, rural Westerners) for the sort of ironic and elegiac vision that gave the South a great literature in the period between the two world wars. The problem with that view is that it assumes that only the trauma of reconstruction (not the historical period but the ongoing reality) can evoke a response in song and story and that once reconstruction has been effected, it results in historical amnesia and artistic paralysis. And yet, it is at least arguable that the South is now producing more good writers, if not as many great ones, as ever before. And with the emergence of regional presses such as Peachtree in Atlanta and Algonquin in Chapel Hill, those writers need no longer be without honor (or profits) in their own country.

In charting the future of Southern literature, one should note that the more recent writers beatified by Flora and Bain (those born in 1930 or later) are all novelists and short story writers. If the Southern Renascence got its start with the poetry and criticism of the Nashville Fugitives, it seems to be maintaining its vitality in the realm of fiction. Not only does the storytelling tradition continue, but Southern narrative appears finally to have gotten out from under the intimidating spectre of the Renascence. Although the Sunbelt setting of much of the region’s contemporary fiction may not possess the baroque richness of Yoknapatawpha, the familiar characteristics of Southern life can still be found in the land of shopping malls and revolving restaurants. Even when they reject family, church, and region, young Southerners are shaped by those forces in a way that those who have not experienced them could never be. The tragic irony at the heart of Yoknapatawpha and Agrarian fiction has mellowed, but what has been gained is an appreciation of the past as past. Southerners are able to know who they are because they have never forgotten what they were.

This review as originally published in the 1987 Fall/1988 Winter issue of Southern Partisan magazine.