We survivors sometimes forget the human cost of our failed War of Southern Independence. The casualty rate for Confederate officers was about 25%. For Union officers it was 10 percent, easily replaced by incoming foreigners.

The loss of talented men—future outstanding leaders, writers, scientists, artists, scholars, builders, clergy, entrepreneurs— was very near catastrophic for the future of the South. The only good news was that there were young men who had survived and been trained in leadership and educated in constructive knowledge by the war.

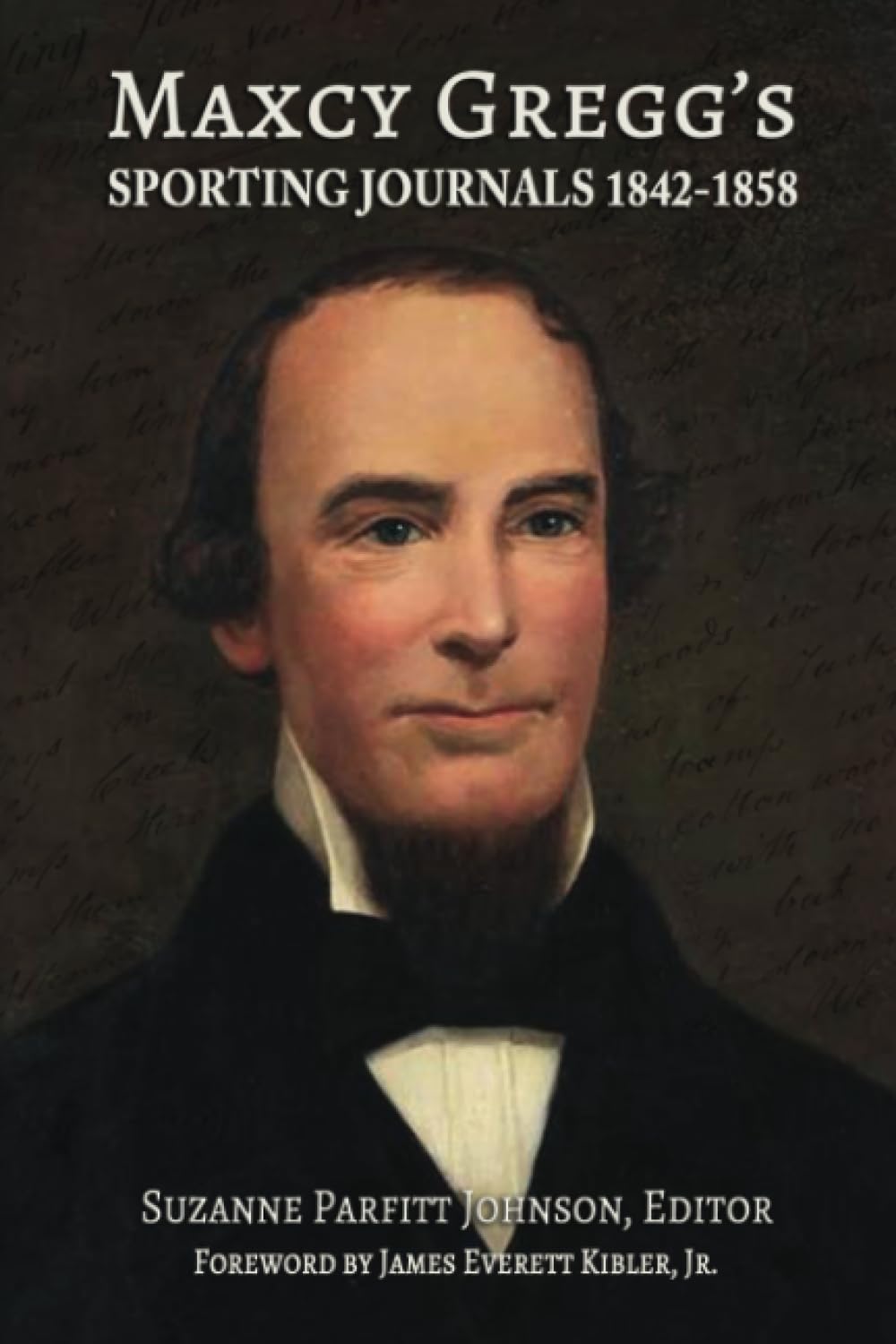

One of the losses was Maxcy Gregg, mortally wounded at the age of 48 commanding a Confederate brigade at Fredericksburg. A lifelong resident of Columbia, South Carolina, Gregg was a talented amateur scientist. He tied for first in his class at South Carolina College. He was the grandson of Jonathan Maxcy, the highly regarded president of the College, and a child of Revolutionary stock, not only in South Carolina, but the heroic naval Hopkins family of Rhode Island.

Gregg had a first class astronomical observatory in his house and was familiar with all the pioneer ornithological literature of the time. Voting for secession in the State convention, he immediately joined the Southern army.

Shotwell Publishing has issued a new paperback edition of Maxcy Gregg’s Sporting Journals, 1842-1858, edited by Suzanne P. Johnson. For more than 20 years Gregg kept a full record of his hunting activities, chiefly all over South Carolina (Upcountry and Low Country), but also in the North Carolina mountains and in Mexico when he was serving as a volunteer captain in the war there.

His handwritten journals have long rested unknown in the South Caroliniana Library until meticulously transcribed for publication by Suzanne Johnson.

As emphasized in the Introduction by Prof. James E. Kibler, the journals provide a rich documentation of more than hunting. We get pictures of the society of the time, people of all classes including the household slaves. We get insights into weather, topography, the writer’s relationship to fellow South Carolinians, other sportsmen and to horses, dogs, and firearms. (Gregg was never able to become as good a shot as he wanted.)

As a hunter he was also a deliberately occupied scientist, recording much information about many different birds. Unfortunately, most of the time identifying and studying the birds required shooting them first. It was the standard of the times. The great naturalist Audubon killed hundreds of the birds he described and painted. It did not endanger the species.

This work provides an original and interesting view of the antebellum South. There has long been in Columbia a Maxcy Gregg Park. As far as I know the jihadist cultural cleansers have not noticed this. Don’t tell them.

General Gregg’s death at Fredericksburg was a terrible loss. I have often wondered why that gap in Hill’s line was left open and uncovered the way that it was.

It’s about time this fascinating and overlooked individual received the attention he rightly deserves.

Fascinating. Thank you, Dr.Wilson.

I would like to get Gregg’s journals for my father.

Ann McLean

Alexander C. Haskell, who served on Maxcy Gregg’s staff, wrote of him in a letter of February 1861, “Col. Gregg is a gentleman and a soldier, as kind as can be and as stern as Brutus.” Haskell loved and admired Gregg, who was mortally wounded at Fredericksburg in December 1862. One of Gregg’s last acts before he died was to dictate a wire to the governor of South Carolina which stated in part: “If I am to die at this time, I yield my life cheerfully, fighting for the independence of South Carolina.”

Excellent. Thanks Dr. Wilson for this call to remember.

Let’s also keep in our hearts Stonewall Jackson’s cavalry officer in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, Gen. Turner Ashby, who also died in (June) 1862. He was considered by many to be one of the most promising fighters of the war. He fell near Harrisonburg. A monument marks the spot, and a high school in nearby Bridgewater is named for him. Valley people honor and guard his name.

The State of South Carolina Historical marker at Maxcy Gregg Park in Columbia, SC was broken off and removed at the beginning of the 2020 “Summer of Love”. All that remains is the post with the fracture clearly exposed. I saw this the day after it happened as I pass by frequently as a local. Confederate General Maxcy Gregg is eternally fighting the war. Did he have a personal connection to what became the park? Did he own that property (then a swamp) before the war? Bird-watching, etc.? There must be a connection as the park was named in the early twentieth century when a living memory of such things could still exist.