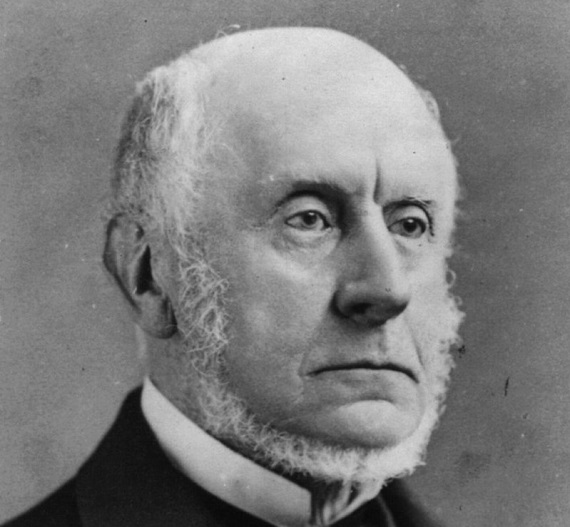

Charles Francis Adams was the grandson and son of former-Presidents John and John Quincy Adams. It is therefore of little surprise he himself embarked on career and life of public prominence as an educator, newspaperman, politician, statesman and historian. Yet, while he never assumed the high offices which the chieftains of his famed family did, the great contributions which Adams did make are often overlooked by historians and unknown at large by the general public today. Chief among these was the moment when, on a far distant shore, in the hour darkest for the Union he served, Adams stood opposed to indulge in a momentary opportunity of emotional nationalism, and for an exemplar of reasoned patriotism. To critically reflect on this noble illustration of the past, to serve as a reminder in contemporary times of the difference between these, is the focus of this work.

Adams’ contributions were far too numerous to comprehensively list in a short work. (1) Suffice to say, despite a less-than mutually warm relationship with President Abraham Lincoln, Adams duly took up his post at the Court of St. James in London. (2) While there, the early success of the Confederate armies, seemingly in the vital Eastern Theater of Operations, provoked derision to which he was subjected. Asked about what his thoughts were of the victories of the Rebel army, his reply was a hallmark of patriotism, “I think they have been won by my fellow countrymen.” (3)

Rather than to extol vitriol in public manner, Adams had summoned the quiet reserve to find and attest to the goodness, no matter how minor or obscure, in his adversaries. He had eschewed, upon severe personal and public capacity, the temptation that lurks in all to engage in a, ‘competition for power and prestige’, which George Orwell defined as the bedrock of emotional nationalism in his landmark work outlining this. As per Orwell-

“By ‘patriotism’ I mean devotion to a particular place and a particular way of life, which one believes to be the best in the world but has no wish to force on other people. Patriotism is of its nature defensive, both militarily and culturally. Nationalism, on the other hand, is inseparable from the desire for power. The abiding purpose of every nationalist is to secure more power and more prestige, not for himself but for the nation or other unit in which he has chosen to sink his own individuality…A nationalist is one who thinks solely, or mainly, in terms of competitive prestige.” (4)

In the moment of supreme trial on many levels for himself, his post and nation, Adams had summoned the quiet assertiveness and courage to not yield to exactly that which Orwell would describe hallmarked just such an emotional nationalist, ”…any implied praise of a rival organization, fills him with uneasiness which he can relieve only by making some sharp retort.”(5) Adams’ conduct was patriotism, personified.

It is only in keeping with critical reflection to recognize that Adams’ mindfulness in the discharge of his mission that under no circumstances ought any Union officials, political or military, at any time give vent to any action or utterance that could be seen as even tacitly recognizing the Confederacy as a sovereign nation and his wording was consistent with this. (6) As well, Adams would give vent to his personal and professional disagreement with the Confederate cause in private. (7)

But notwithstanding, his actions in the hour of trial of resisting temptation must be seen in the same light as when Sitting Bull and Crowfoot set aside the ancient differences of their respective Aboriginal nations of the Sioux and Blackfoot to attempt to ensure peace and to share access to buffalo herds as equitably as possible for all upon the Canadian and American prairies, Aboriginal and non, (8), or when during the Irish Civil War, Tom Barry recorded looking down from his cell in Kilmainham Gaol upon the sight of a thousand of his fellow Anti-Treaty prisoners-of-war all kneeling in prayers of tribute upon the death of General Michael Collins, the Commander-In-Chief of the Irish Free State forces whom they opposed. (9)

In our contemporary times, the study of history and historiography has seemingly taken on a form of increased division. In order to attempt to regain respecting the differences between patriotism and nationalism and the value of reconciliation, the memory and examination of the heroic and quiet courage of Charles Francis Adams must stand as an exemplar. What might be the message of his echo with regards to his countrymen today? That all are Americans. And it is in this very vein of patriotism that all citizens of the world might find inspiration.

‘Lest We Forget,

The Blood Price and Death Debt.

Respect and Honour for they,

Who wore the Blue and the Gray.

They sleep, forever, in The Hall,

Americans, all.’

NOTES:

(1) Among these would be production of the pamphlet, Texas & The Massachusetts Resolutions, Boston: Eastburn’s Press, 1844. On page eight, Adams’ writes, “War with Mexico…is of no trifling importance. A war to protect slavery against the civilized world is the ultimate point of degradation to which a nation,boasting to be free, is likely to be driven.” Nor should it be overlooked that at the start of the Civil War/War Between The States, he had advocated New Mexico to be granted statehood without any prohibition on slavery. See Donald, David H., Lincoln, Simon & Schuster, 1995, 269. Also refer to the preface of the pamphlet, The Complaint of Mexico & Conspiracy Against Liberty, Boston: Published by J.W. Alden, 1843, by George Allen and Daniel Webster. “The following pages [are meant] to expose the dishonest policy of the Government of the United States, in its intercourse with Mexico, to annex Texas to the United States, for the extension and perpetuation of Slavery…”

(2) The President made plain that he was assigning Adams the ultra-important diplomatic post solely out of the latter’s relationship with Secretary of State, William H. Seward, and equated the matter as if as meager an appointment to the Chicago Post Office. See Donald, Lincoln, 321. Adams would in turn record in his personal manuscripts, “My fear now is that the breach is complete. Perhaps this is not in the end to be regretted so much, as the Slave States always have been troublesome and dictatorial partners…Mr Lincoln has plunged us into a war.” Charles Francis Adams Civil War Diary/Massachusetts Historical Society, 15 April 1861 [Accessed 18 September 2019].

(3) Hill, Frederick Taylor, On The Trail of Grant & Lee, New York & London: D. Appleton & Company, 1911, vii.

(4) Orwell, George, ‘Notes on Nationalism’, Polemic, October, 1945.

(5) Ibid.

(6) See for example, Harris, William C., ‘The Hampton Roads Peace Conference: A Final Test of Lincoln’s Presidential Leadership’, Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Vol. 21, Issue 1, Winter 2000, 30-61, and the diary entry of US Minister of the Navy, Gideon Wells, for 25 November 1864. At the same time, Adams’ response can perhaps be viewed as befitting of the spirit of his President, who had stated in 1861 a similar ode of subtle respect to the Confederates, “We must not forget that the people of the seceded states, like those of the loyal states, are American citizens with essentially the same characteristics and powers. Exceptional advantages on one side are counterbalanced with exceptionaladvantages on the other. We must make up our minds that man for man, the soldier of the South will be a match for the soldier of the North, and vice versa.” See, Nicolay, John G., & Hay, John, Abraham Lincoln: A History, New York: The Century Co., Vol. IV, 1890, 79.

(7) His diary entry for 1 November 1864 reads, “At home all day. Read the American newspapers, and especially the report by Judge Holt Judge Advocate General of the secret organization in the West, which has been in treasonable cooperation with the rebellion for the purpose of overturning the federal government.” While the issue, in light of all possible arguments, evidence and precedents in the legal aspects, as to whether the Confederates had actually been guilty of treason or not will likely remain a contentious debate, the more important aspect of this evidence, for the purpose herein, is to show Adams’ humanity in giving vent to his anger.

(8) Dempsey, Hugh A., Crowfoot: Chief of the Blackfeet, Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1976, 91-92; MacEwan, Grant, Sitting Bull: The Years in Canada, Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1973, 134-39, 154-55, 205. There had been the potential for a veritable blood-bath from organised Aboriginal resistance to the colonization from White settlers in the 1870s. After Sitting Bull’s arrival in Canada following his victory at Little Big Horn, the 5 April 1878, Fort Benton Record, as cited in MacEwan, recorded he was, “apparently sparing no effort to form a league among [these] congregated tribes…and…called upon the assembled Indians to witness…how easy[it would be] to clean out all the Whites and have the country…”

(9) http://www.generalmichaelcollins.com/on-line-books/michael-collins-his-life-times/12-the-ambush/ [Accessed 18 September 2019]. “There was a heavy silence throughout the jail and ten minutes later from the corridor outside the top-tier of cells, I looked down at the extraordinary spectacle of about a thousand kneeling Republican prisoners spontaneously reciting the Rosary aloud for the repose of the soul of the dead Michael Collins…I have yet to hear of a better tribute to the part played by any man in the struggle with the English for Irish Independence.”