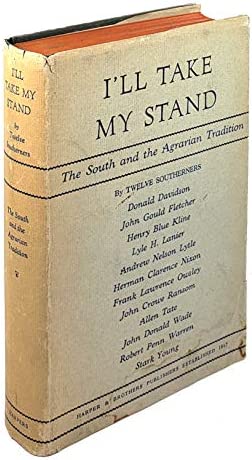

I’ll Take My Stand contains a vivid description of rural Southern life by Andrew Lytle: “The Hind Tit,” which I always associate with my Thanksgiving memories, despite its not being specifically about Thanksgiving. (The title refers to the poor nourishment left to the “runt” Southern States by the American empire after the War Between the States.) The farm life that Lytle describes – the milking of cows, the making of butter, home remedies, folk dances, etc. –always seemed from another world to me, but the closeness of family, especially at the dinner and supper table, was perfectly familiar. The season also reminds me of Truman Capote’s immortal story, “A Christmas Memory” – in my judgment superior to much of his other work, like his “non-fiction novel” In Cold Blood, which I spent a high school semester reading at the bus stop every morning.

Thanksgiving always meant being with my grandparents, especially my grandfathers – the paternal one from Georgia, and the maternal one from Texas. Like most Southern kids, I never called either one “grandfather.” It was always “Paw-paw Hulsey” or “Paw-paw Cagle.”

In my pre-school days my family lived with the grandfolks in Georgia. I remember the weather always being cold by Thanksgiving. That meant sleeping under dozens of hand-made quilts – warm, but a real felt weight on top of you. I would wake up to hear Paw-paw talking – unusual since during the week he would have been at work long before I crawled out of bed. I would thump over the pier-and-beam wooden floor to the living room, where Dad would already be dressed, standing with his hands behind him, his back turned to an old Dearborn gas floor heater with a half-dozen upright ceramic bricks glowing inside. In the kitchen the ladies would already be at work, in my earliest years making biscuits by hand, to arrive on my breakfast plate steaming hot, dripping with butter and honey. In some years there was jelly, hand-picked from wild grapes and put up in little jars with a slab of paraffin sealing the top.

The Thanksgiving meal really began well before the appointed Thursday, when the ladies started baking pies, thawing the turkey, and preparing the stuffing. The stuffing consisted of bread and cornbread saved over the whole month. My mother, grandmothers, and aunts pinched apart this bread and seasoned it – always with a fuss over just how much sage to add to it. When the full complement of maternal kin was on hand, the pies were made from scratch; otherwise a concession was made for buying a frozen graham cracker crust for pumpkin pies and lemon meringue pies, or flour crust for apple pies and chocolate pies. Pecan pies were always from scratch. You would never see a cranberry in the cranberry sauce that was offered: It was always a cylinder of jelly slipped out of the can, sliced but with the rings from the can visible around it. There was always cornbread, moist but firm, striking that elusive balance between too firm and too crumbly to take butter. The Texas version would have chopped jalapeno inside. A big serving boat would be filled with giblet gravy, rich with chopped boiled eggs. Boiled eggs made a separate presence, cut in half and stuffed with a yolk-and-mustard mix topped with paprika. A gigantic bowl of mashed potatoes would typically be spooned from, as it was too heavy and hot to pass around. It would be in adulthood when I learned the secret of their creamy magnificence: The addition of mayonnaise and heavy cream. Vegetables were usually from jars put up through the year from the garden behind the house, or received from neighbors who had a garden. I must say that these were my least favored dishes, since the green beans would usually be snapped without removing the strings along the side, and overcooked nearly to mush. Of course the big turkey was there, and later the “spiral-cut honey ham” baked with sliced pineapple rings on top. Drink was always Southern sweet tea, but always sweetened not with cane sugar but with saccharin tablets, to save us all from certain death from “sugar die-BEE-teez.” Dad favored iced milk, and Paw-paw Hulsey liked a glass of cornbread filled with buttermilk, though most often that was taken as a separate treat.

Paw-paw Hulsey would threaten to give the terse and irreverent blessing from one of his dead relatives:

O Lord, peep down through that crack

And watch old Newt cram it back!

The habit was to have this feast at dinner (“lunch” for Yankees), with smaller portions and pies taken for supper. In the intervening afternoon the men and boys would walk outdoors, most often to go collecting pecans. Often the conversation among the men was about crops –which, as Texas historian A.C. Greene also noted in his book A Personal Country (ISBN 978-1574410532, page 218), surprisingly revealed even non-farmers conversant in the subject. Sometimes I and my cousin Tony would climb magnificent pecan trees – some of them over 50 feet high – in order to shake down the pecans where the thrown sticks could not reach. This afternoon pecan gathering eventually would fall out of practice in Texas: In every public space the Mexicans (pronounced “MESS-cuns” in those days) would have always picked the nuts clean before Thanksgiving, even when they were still in their thick green husks.

I took a long detour from this heritage. I did not find the meaning of the South in many of its representatives. Most of the authors of I’ll Take My Stand would themselves eventually repudiate their manifesto as bucolic romanticism, and the Agrarians’ anti-industrialism I thought to be just a skirmish apart from the much more threatening anti-industrialism of the 1960s counterculture – the real intellectual theater of war, in my view.

Indeed the 1960s were one long temper tantrum of a young generation that, unlike nearly every generation before it, stood rootless, outside the influence of its parents. I found the antidote to the influence of that generation, as so many did, in the strange figure of Ayn Rand – the Donald Trump of modern philosophy. She was so stridently right on the issues of the day, as her essay “Apollo and Dionysus” and her book Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal evidenced. But as much as she praised Aristotle and styled herself a philosopher, aside from a few pages on “unit-economy” in epistemology, she had no depth in the subject. Never did she have a serious exchange with any scholar; culturally she was shallow, with no extensive reading and with only one reference to classical music over her entire output (Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony); she gave scant public attribution of her intellectual debt to Isabel Paterson (The God of the Machine) and none to Garet Garrett (The Driver); never did she systematically challenge the ideas of the day, nor even systematically describe her own philosophy of Objectivism: All of her writings were fiercely polemical, not logically discursive. Probably her most lasting work will be in the area of moral philosophy, as Isabel Paterson believed – and even that resting on just a few pages in The Virtue of Selfishness. It was this book, read when I was 14 years old, that launched my long detour into fields far from any study of the South. I remember my friend David Merrick timorously bringing the paperback to me, saying, “Look, Hulsey, Rand is saying everything opposite to the Bible.” And he held it out to me fearfully, as if it were a stick of dynamite.

It would be much later when I would encounter “serious” defenders of the Southern tradition. I was first impressed by the 1941 The Mind of the South by W.J. Cash (despite its failings, catalogued on this site) and the 1955 The Burden of Southern History by C. Vann Woodward. At the University of Dallas I would encounter M.E. Bradford, who taught at the school for a time, and Eric Voeglein, whose massive Order and History was the hot topic during my few years there.

Detours, quests, adventures – what abides from all that? For the Southerner, it’s found in the familiar, the local, and the personal.

For me, it’s the sepia photo of my Paw-paw Hulsey, sitting in a chair, holding the ankle of a crossed leg in English clubman style, wearing knee pants and a newsboy cap. He is in his 20s, his big face and broad shoulders proof that, as he claimed, he could lift a horse on his back. More than that, he at times carried three families on his back, working as a master plumber – underpaid, but never complaining. He only asked for a nickel to buy a “Co-Cola” out of the Coke machine at work, to have his way with the TV for one show a week, his “Sat’dy Night ’Rasslin’,” and maybe a pack of Old Gold or Chesterfield cigarettes. I never once saw him angry. He was my rock, just like my Paw-paw Cagle, who shoveled coal, and who worked as a “lint head” in the Denison cotton mill, as a boat builder, and a carpenter. Never complaining about their lot, they were grateful for work, no matter how hard or how badly paid – the kind of men who brought their kin through the Great Depression.

On this day I reflect how deeply grateful I am to these folks of mine, as I sit here quietly by myself, looking out the window, just sitting here. They are what Southerners have always called “good people”: Unpretentious, honest, the salt of the earth. They are my blood, laid in the Georgia and Texas ground, awaiting the Resurrection.