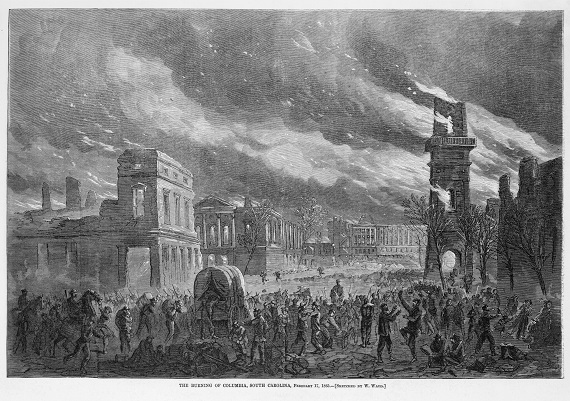

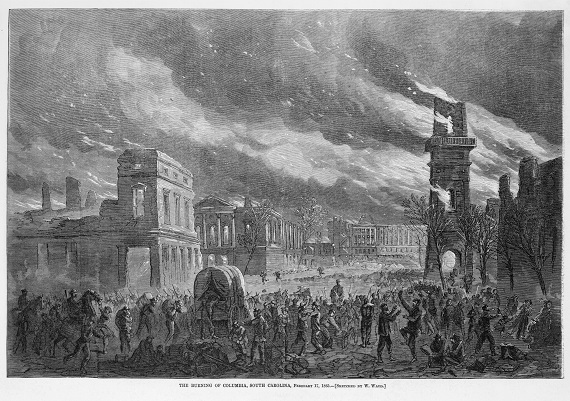

When you hear or read about the burning of Columbia, General Sherman’s principal target in South Carolina, you are often told that the origin of the fire is a historical mystery that can’t be conclusively solved, or that the fires were actually initiated by the evacuating Confederate troops, or even by the citizens of Columbia themselves—none of which is true.

In her recent book Sherman’s Flame and Blame Campaign, journalist Patricia McNeely investigated why such falsehoods about the burning of Columbia have persisted over the decades, despite the fact that she had “read an avalanche of eye-witness accounts that leave no doubt that General William T. Sherman’s drunken troops burned Columbia.” Before Columbia was surrendered on February 17, 1865, some cotton bales had been placed in the middle of Main Street “in order to be burned to prevent their falling into the possession of the invaders,” as it was stated in an official report compiled by a committee of Columbia citizens. The Confederate commanders, including General Wade Hampton, however, were afraid this might endanger the town and issued explicit orders that the cotton should not be burned, and subsequently the Confederate forces withdrew from Columbia leaving the cotton bales in the middle of the wide street (which was muddy from an overnight rain).

As Sherman’s forces filled the city the morning of February 17, some of the cotton bales were set afire, some said from the cigars of the soldiers, but these smaller fires were completely extinguished by mid-afternoon. The fires that destroyed much of the city did not begin until about 8 o’clock in the evening. The following day, Sherman attributed the burning of the city to his drunken troops. Not long afterward, however, he claimed that General Wade Hampton was responsible for the city’s destruction and that Hampton’s men had set the cotton on fire before departing. Ten years later, when Sherman’s memoirs were published, he admitted that he had laid the blame on Gen. Hampton merely to shake the confidence of the South Carolina people in their hero Hampton.

Lt. Colonel George Ward Nichols was one of Sherman’s staff officers. His war memoir, The Story of the Great March, came out in 1865, and two years later, he met “Wild Bill Hickok” (James Butler Hickok) and published a story about this Old West folk hero in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. It made Hickok famous but was widely criticized for false and exaggerated accounts of his exploits. In 1866, Nichols published an article in the same magazine entitled “The Burning of Columbia.” In this laughable and disingenuous account, he not only laid the principal blame for the calamity on General Hampton, but also suggested that most of the pillage of the city had been committed by Confederate cavalrymen under the command of Gen. Joseph Wheeler. There is overwhelming evidence—most of it eyewitness testimony—that Sherman’s soldiers began stealing and pillaging from the moment they broke ranks in the city. This sacking of Columbia went on all day as well as during the night of the fire, and into the following day.

In “The Burning of Columbia” Nichols described a conversation he had the night of the fire with a Mr. Huger, “a well known citizen of South Carolina,” in which he claimed that Huger confirmed to him that Wheeler’s men had been pillaging Columbia. It turns out that this “well known citizen” was Mr. Alfred Huger of Charleston who was in Columbia in February 1865 with his family. In August1866, when he found out about Nichol’s article, Huger wrote a response to the editor of the New York World, denying, among other things, that the conversation reported by Nichols ever took place:

THE BURNING OF COLUMBIA

Letter from Hon. Alfred Huger

Charleston, S.C., August 22 [1866]

To the Editor of the World.

SIR: I most unwillingly leave the retirement and obscurity which old age and circumstances have provided; but a remark in your paper of the 13th seems to demand it. A writer signed “S,” replying to an article in Harper’s Magazine for August, introduces my name in these words: “This must refer to Alfred Huger, for many years postmaster at Charleston,” &c. &c. I turn to the Magazine, and to my surprise I find a contributor, whose purposes and motives it is not my business to define, making capital out of so barren a subject as myself. Beginning with the “Burning of Columbia,” and the abuse of General Hampton, he says: “Among others to whom I was sent to give assistance was Mr. Huger, a well known citizen of South Carolina,” and then recounts an elaborate conversation about a band of thieves calling themselves Wheeler’s cavalry, &c., and in another part of his narrative writes: “When the citizens of Columbia begin their investigations of the burning of that city, and the pillaging of houses and robbing of citizens, let them not forget to take evidence of Mr. Huger!” I am thus put on the stand without being consulted, and shall commence by saying that if this individual or any other was ever “sent” to my “assistance,” the mission has been strangely disregarded. I never saw any such person as he claims to be, though I was an eyewitness to the burning of Columbia. I never had any such intercourse with any human being in General Sherman’s army, or out of it; and if investigations are made and the evidence of Mr. Huger is called for, I shall, with a deep consciousness of what is due to truth, say that, before Almighty God, all that I saw, all that I heard, all that I suffered, all that I believe, is in direct opposition to what is affirmed by the writer for Harper’s Magazine, and from which he quotes Mr. Huger as a portion of his authority; and I ask leave to add, after maturely reflecting upon the events of that fearful night, when every feeling of humanity seemed to be obliterated, if my “well-being” here and hereafter depended on the accuracy of my statement, I would say that the precision, order, method and discipline which prevailed from the entrance of the federal army to its departure, could only emanate from military authority. How could I come to any other conclusion with the fact, regarded as indisputable, that the city was doomed before it was taken? And that as the tragedy progressed, everybody saw the programme carried out, as they had previously expected? Or how am I to believe the evidence of my own senses when an individual pretending to be an officer, talks of burning the city, pillaging houses, robbing citizens, &c. as if “these” were unfounded charges? Why, sir, I never supposed I was dealt with more hardly others, because I knew that the “plunder” was universal. Yet Mr. Huger who is to bear witness for one who was sent to assist him, now declares that he was mercilessly robbed; that his person was ruthlessly violated; that food was taken away from his orphan children, and that his family were brutally insulted by well mounted and well armed men in the uniform of the United States! For aught I know, it may be usual or even necessary to grant this license, while the denial is equally absurd and wicked, and the attempt to implicate other people in the consummation of both! But this is the end that such things that such things come to, and the natural consequence of calling witnesses to prove what the witnesses themselves know to be false. I saw those who were apparently plying their vocation deliberately set fire to houses, carrying with them combustible preparations for doing so. Of the effort made to prevent them I say nothing, because I saw nothing. It gratifies me, however, to relate this instance of kindness. My own house was about to be destroyed by the firing of an adjoining building. There were two western men looking on—soldiers in the true sense of the word. I asked one of them (their names were Elliott and Goodman, one from Indiana, the other from Iowa), “Have you a family at home?” The man showed that he had a heart, and, as the incendiary moved off to other subjects, he did assist me, without being “sent,” and with my servants, and the only child big enough to “hand a bucket,” we saved the house, with its helpless inmates, thanks to the Good Samaritan.

My conviction is that Columbia was cruelly and uselessly sacked and burned, without resistance, after being in complete possession of General Sherman’s army; but who gave the “order” to apply the torch is not one for the victims either to know or to care. Hundreds of helpless women and children were turned out to their fate. It is the historian’s business to find evidence to meet the case, not mine, and my voice would never have been heard had I not been unjustly dragged before the public. The “truth,” and the “whole truth,” will probably never appear; but it is “recorded in the high chancery of Heaven,” where no power can make the erasure.

Mr. Editor, I crave your patience a little longer, and beg your attention to the first sentence of the article of which I complain. It reads thus: “If Mr. Wade Hampton is anxious to add a deeper shame to a dishonored name, he has attained that end and by his renewed attempts to hold General Sherman responsible for the burning of Columbia and its terrible consequences,” &c. Now, sir, I speak for every honest man between the mountains and the seacoast, and between the Savannah river and the Peedee, when I say, “If this opinion and this epithet are not equally revolting and insulting, then the common sensibilities of nature are made extinct by the sufferings we have endured.” If “Hampton” is a “dishonored name,” then there is none within the limits of this down-trodden and persecuted State that can be considered as unsullied. Here in South Carolina, add throughout the South, every human being feels that where the name of Hampton is best known it is the most revered, and he who bears it is the most beloved. Before the present incumbent saw the light that name was identified with all that is brave and honorable and generous. What a noble sire (who emphatically and habitually “did the honors” of his native State) has left impressed upon the hearts of his countrymen as a legacy to his children, this slandered Mr. Wade Hampton, the Lieutenant-General of the Confederate army, will transmit to another generation, bright and untarnished. If there is one among us more cherished than the rest, it is he, upon whom the gratuitous assault is so brutally, and yet so feebly made. And if today, or tomorrow a canvass should be opened for our “representative men,” to fill the highest office in the gift of a heart-broken but grateful people, none could be found strong enough to compete with him for their favor. And it would be untrue to the living and the dead, if such were not the unanimous decision. I have said that the historian must find evidence as to the burning of Columbia, and he will find it; the foolish attempt to hold Hampton responsible, is beyond the tether of his last calumniator, and is hardly worthy of a serious refutation. These few questions, when they are asked, will be found difficult to answer. Where was Hampton when the conflagration began to take its regular course at eight o’clock at night? Did the cotton which was burning at the east end of Main street travel against a gale of wind to the extreme west, more than a mile off? Was it not there and then that we were called on to perceive that our doom was sealed? Why talk of putting out the fire in a church-yard when it is notorious that the sacrament silver belonging to the altar was stolen, and I think, subsequently given up? Did Hampton burn the country-seats surrounding Columbia, leaving his kith and kindred without a shelter? Did he burn the farm-house on the wayside and away from the wayside? Every grist-mill and flour-mill? Did he burn Camden, and Winnsborough, and Cheraw? Was the quantity of silver-plate taken from the citizens of Columbia sold for Hampton’s benefit in New York and elsewhere? Is it the necessary province of war to obliterate all mercy and shame? But enough, when the Searcher of Hearts commences His “investigations,” Hampton will be found entrenched by truth—surrounded by that strength, which “prosperity and victory” cannot give, and which “adversity and malignity” cannot take away.

Mr. Editor, we are doing our best, with Heaven’s help, to have a country once more. North, South, East and West are enlisted in this holy enterprise. All have joined hands in this sacred work, and a Chief Magistrate, distinguished for his high inflexible “courage” in its performance, wisely tells us: “If we cannot forget the ‘past’ we can never have a ‘future’”; and standing as I do, almost in sight of the grave, among the oldest men in the State that gave me birth, I will say Amen to that sentiment. Let the past be forgotten, is such is possible; at any rate, let it not be referred to if the object is “peace” and the “hope is in the future.”

I am, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

ALFRED HUGER

I would like to thank Dr. Jim Kibler for bringing this letter to my attention.