Editor’s Note: O. Henry’s “The Gift of the Magi” is one of the most popular Christmas short stories, but most modern Americans know little about the author or his Southern background. O.Henry posted caricatures of the local carpetbagger in the drugstore window. He also said that when he heard “Dixie” he did not celebrate but only wished that Longstreet had…This piece was originally published in the 1915 edition of the Methodist Quarterly Review.

It has been only a few years since William Sidney Porter, who was known to the reading public as “O. Henry,” flashed like a meteor upon the world, only to dazzle us with his brilliance for a while and then suddenly to pass away. It has been not quite five years since his untimely death, and we who read his charming stories as they appeared in the magazines are probably not far enough removed from his brief day to render a dispassionate and unbiased verdict of his art and accomplishment. We are perhaps too near his time to see him in proper and true perspective. Yet it may not prove altogether unedifying and unprofitable to review his work and ascertain how far his vogue was justified and upon what elements of permanency it reposes.

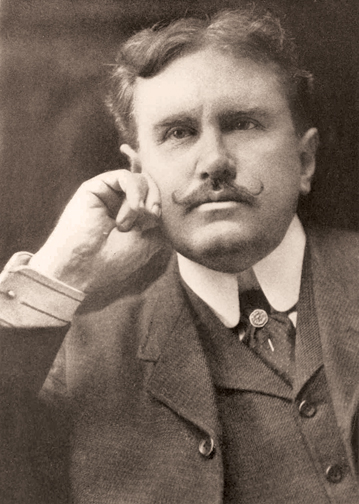

Since no biography of O. Henry has yet appeared, it may be advisable for the benefit of his readers not familiar with the facts of his life, in the first place, to weave in this paper a sketch of his meteoric career.

I.

William Sidney Porter was a post-bellum son of the Old North State, being born at Greensboro (North Carolina) in 1867. His father was a physician, Algernon Sidney Porter, and his mother a granddaughter of a sister of Governor Jonathan Worth. Upon his mother’s death, young Will-as he was familiarly called-at a tender age, was left to the care of his maiden aunt, Miss Evelena Porter, to rear. She presided over her brother’s household and conducted a school next door at the same time. In this school in Greensboro young Porter obtained the rudiments of an education-the only schooling he ever had. But by her systematic reading of selections to her pupils, Miss Lena Porter, as she was known, inculcated in her nephew a nice appreciation of literature, which was to linger with him as an abiding inspiration.

After his brief school-days, young Porter, at the age of sixteen, found employment as a prescription clerk in a local drug store of his uncle; and here in the Porter drug store there gathered around the boy a small group of congenial companions much his senior. It was here during his leisure hours that he busied himself with pen and pencil, with sketching and drawing, of which he was very fond. At sixteen he wrote a play, which elicited the hearty commendation of his drug-store comrades. But the exacting confinement of the drug store soon began to undermine young Porter’s health, and in 1883 he made his way to Texas, where he lived on a ranch and, as he himself wrote, “ran wild on the prairies.” He did not work as a miner or a cowboy, as is sometimes stated. It was here, from his keen observation, that he acquired the intimate knowledge of life in that wild country which he afterwards turned to good account in his fine collection of stories called Heart of the West. While living here on the ranch of his friend Dr. Hall, Porter wrote his first stories of Western life, destroying them as soon as written, and sketched that now famous series of illustrations for Dixon’s Carbonate Days that was destined never to be printed. When Dixon destroyed the manuscript of his Carbonate Days and threw the fragments into the Colorado River at Austin, he fortunately preserved the forty illustrations Porter had drawn for the book; and now they are highly prized as among the earliest specimens of Porter’s work.

In Texas, Porter lived in an atmosphere of adventure and was involved in many an escapade, for he was full of fun and passionately fond of a joke. On recovering his health, he moved from the ranch to Austin and secured a position in the State Land Office, and later in the First National Bank. He then ventured into journalism, buying the plant of a feeble newspaper-the Iconoclast-which he subsequently issued from his Austin office under the title of Rolling Stone. This venture proved successful at first, and the paper increased its circulation as a humorous weekly. But Porter’s sprightly and trenchant paragraphs in the Rolling Stone soon offended the German element of his clientage, and the subscription list began to dwindle. Then the Rolling Stone decided to engage in a local political fight which spelled failure for the little sheet, and it suspended publication in 1895. Thereupon Porter moved to Houston and secured a position on the Post, which paid him the sum of fifteen dollars a week, with the assurance of the editor that within five years the cub reporter would be earning seven times that amount on one of the great New York dailies-an assurance that carried, unfortunately for Porter, no guaranty of its fulfillment. After one year in Houston, Porter left the Lone Star State, where he had spent a third of his life, and made his way to Central and South America.

Will Porter, or Sidney Porter-as he was called after his Texan days—was a rover, a rolling stone, and showed himself a daring adventurer. He went into his voluntary exile in Central America at the suggestion of a friend who “intended to go into the fruit business,” but he soon learned that he was the victim of his own abounding credulity by which he had been duped again and again. As Porter himself informs us, most of the time of his self-imposed exile he “knocked around with refugees and consuls.” In his Cabbages and Kings, his earliest book, he has preserved for us his experiences and impressions during this chapter of his checkered career. This volume is his nearest approach to a diary, and it affords very clever and spicy reading. After his sojourn in that land of revolutions and half-breeds, he returned to Texas for a short stay, and then took his final leave of that State, never to see it again. He betook himself to New Orleans, “where he began to work more consistently as a writer.” Here he first made a reputation as a story-writer, offering the products of his fertile pen to various magazines. He utilized his observations and experiences in the Crescent City in some of his stories with their distinctive local color, such as “Cherchez la Femme” and “The Shamrock and the Palm.”

During those formative years he proved himself a diligent and apt pupil in the hard, practical school of experience. We do not know what feelings and thoughts engaged his attention other than the ever-burning desire some day to be a writer. To this end he had served his apprenticeship in the various newspaper offices in which he found employment. But it would be extremely interesting to know what authors especially he selected as models and where he learned the technique and art which he practiced so successfully during his last halcyon years in New York, the city of his adoption. In an interview shortly before his untimely death, he gives us at least a glimpse of his reading during his formative period. He says: “I did more reading between my thirteenth and nineteenth years than I have done in all the years that I have passed since then. And my taste at that time was much better than it is to-day; for I used to read nothing but the classics. Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy and Lane’s translation of the Arabian Nights were my favorites.”

Here, then, Porter tells us his two favorite authors during his early years. But there is absolutely nothing in these staid classics that contains the promise of his brilliant achievement or of his salient characteristics as a writer. If he had confessed that in his formative period he spent his days and nights with Villon or Maupassant, or with our own Hawthorne and Poe, we could then explain his exceptional constructive gifts and his marvelous technique. But those most familiar with Porter’s life and habits assure us that he was unacquainted with those famous French writers in his early life, and that if he ever read them it must have been in his mature years after he had taken up his residence in New York and established his reputation as a story-writer. No doubt O. Henry knew Hawthorne and Poe, but he does not tell us so. Yet there is a considerable difference between the tales of Hawthorne and Poe and the short stories of O. Henry, especially with respect of language and style. The language of Hawthorne’s and Poe’s tales is as chaste and pure as a crystal; that of O. Henry’s stories, on the contrary, is the vernacular of the soil and abounds in the most piquant and picturesque slang. The speech of O. Henry, too, is often a contributory factor in the effect of his stories; but this is in no sense true of Hawthorne and Poe. All three authors, of course, had the happy faculty of producing the desired effect in a few pages, “the unerring instinct for ending the story at just the right instant.” All three, to be sure, were masters of constructive, technical skill, and knew how to produce “the sharpest possible narrative effect,” but they differed widely as to methods. However, if O. Henry was a pupil of the Poe and Hawthorne school, he was no servile imitator, but possessed an originality quite as striking as theirs, and he far surpassed them in point of humor. But as for humor, Poe did not have it in his equipment and had almost no appreciation of it.

The next chapter in Porter’s life revolves about his residence in New York. On leaving New Orleans, Porter drifted to New York. In 1902 he accepted an offer from Ainslee’s Magazine to write a dozen stories at the price of one hundred dollars apiece, and so took up his residence in the great metropolis. The big city seems to have exercised a wonderful fascination over him. “To him it was even a thing of amazing mystery, a veritable Bagdad on the Subway, where Aladdins were continually rubbing their wonderful lamps and the emissaries of countless bands of Forty Thieves were placing chalk marks on doors.”

In his “Lady Higher Up,” O. Henry has preserved for us his impressions as he first beheld the gateway to the city, the harbor of New York. His imagination pictures a dialogue between Mrs. Liberty, impersonating the statue of Liberty in the harbor, and Miss Diana, impersonating the statue of the goddess surmounting Madison Square Garden. Another story, “Brickdust Row,” was probably intended to reflect the sensations the author felt as the view of the “Big City” gradually broke upon his enraptured vision on beholding New York from the deck of an ocean liner slowly steaming in past the immense illuminated wheels and towers of Coney Island. He supplemented these first impressions later by his imagination, and reproduces them, with the details filled in more fully with the local color, in “The Lickpenny Lover.” As he explored the bustling city, deviating from the main thoroughfares and arteries of traffic, he was more and more impressed with its ever-shifting scenery and its picturesque faces and figures. One of his favorite haunts was Fourth Avenue, and he embalmed its cosmopolitan features in “A Bird of Bagdad,” graphically describing its teeming life from its beginning in the Bowery to its headlong disappearance in the tunnel in Thirtyfourth Street. He portrayed in his stories several of the city’s squares, as for example, Madison and Union, using them as a suitable background for the human derelicts-the bread-linersthat frequent those parks and habitually occupy the public benches. Here he laid the scene of such stories as “The Fifth Wheel,” “Two Thanksgiving-day Gentlemen,” “The Assessor of Success,” “Squaring the Circle,” etc. But Gramercy, with its aristocratic surroundings and locked gates, he selected as the proper setting for his stories dealing with the foibles of the Four Hundred, such as “The Defeat of the City,” “The Marry Month of May,” etc. Sixth Avenue furnished the background for the characters that figure in “The Fairy of Unfulfillment.” In this same thoroughfare the Man from Nome found the Girl from Sieber-Mason’s, and Greenbrier Nye discovered his old friend of the plains, Longhorn Merrick, and heard “The Call of the Tame.” The East Side provided a suitable setting for the underworld characters that masquerade in “Past One at Rooney’s”; and here, also, in a Second Avenue boarding house, O. Henry laid the scene of “The Count and the Wedding Day.” In East Side, too, in Orchard Street, was localized “The Coming Out of Maggie”; and farther up in that quarter of the city were the Beersheba Flats, whence the motley crowd of tenants were forced out into “The City of Dreadful Night.”

O. Henry’s vivid imagination invested this “Occidental city of romance,” with its kaleidoscopic scenes and teeming grotesque figures, with all the magic and glamour of the Arabian Nights. Though he must have traversed the thronged streets of the entire city, he never lived far from Madison Square during all his eight years’ residence in Manhattan. Here he spent the most productive years of his life; and here, too, in his adopted city of “Four Million” so dear to his heart, he died, June 5, 1910, having hardly reached the meridian of life. Though so fond of the gay life of the metropolis, O. Henry himself appears to have been of a retiring disposition, and not especially sociable. The fact is, he gave but little thought to society, and the very title of his collection of stories of New York life-“The Four Million”-is an eloquent protest against the unfounded claims of the exclusive Four Hundred. He was so reserved and so uncommunicative that he seemed a veritable man of mystery to those who had but a superficial acquaintance with him. He was very reluctant to be “interviewed,” and imparted scant information about himself.

O. Henry offered his first hostage to fortune in Cabbages and Kings, in 1905. This was followed the next year by The Four Million. Then came The Trimmed Lamp and The True Heart of the West, in quick succession. O. Henry’s genius was very fecund, and The Voice of the City, Roads of Destiny, and Options, were speedily given to the world, in the order named. Most, if not all, of the stories constituting these books had previously appeared in various magazines. Several of his stories and one or two of his twelve volumes-among them Whirligigs and Rolling Stones-were published posthumously. The last story of his facile pen was “Adventures in Neurasthenia,” which was printed in the Cosmopolitan Magazine after his death, as was also his splendid story “A Fog in Santone.” A pathetic interest attaches to “The Dream,” because it was left unfinishedsad autumn’s last chrysanthemum. After O. Henry “arrived” as a writer, editors vied with one another in bidding for his stories, and his copy is said to have commanded a price surpassed only by Kipling’s. O. Henry’s meteoric career endured only eight years. When his biography is published, we shall know more about the facts of his life. Till then, we must content ourselves with the tantalizing glimpses we discover now and then in his stories where fact and fancy are so freely commingled, and with such information as we can garner from the popular magazines, especially The Bookman.

Very few of his letters have been given to the public. But these few afford a delightful sidelight on his character. Two of those addressed to his little eight-year-old daughter Margaret, who was then living near Nashville, Tenn., with her grandparents, breathe a note of charming naïveté, and are very quaint. In one of these he writes:

Dear Margaret: Here it is summertime, and the bees are blooming and the flowers are singing and the birds making honey, and we haven’t been fishing yet.

In the other, he represents himself as a Brownie, and begins as follows:

Hello, Margaret. Don’t you remember me? I’m a Brownie, and my name is Aldibirontiphostiphornikophos. If you see a star shoot and say my name seventeen times before it goes out, you will find a diamond ring in the track of the first blue cow’s foot you see go down the road in a snowstorm while the red roses are blooming on the tomato vines. Try it some time. I know all about Anna and Arthur Dudley, but they don’t see me. I was riding by on a squirrel the other day and saw you and Arthur Dudley give some fruit to some trainmen. Anna wouldn’t come out. Well, good-by; I’ve got to take a ride on a grasshopper. I’ll just sign my first letter-A.

II.

It is quite time now to consider O. Henry’s work from a critical point of view. All critics are agreed that O. Henry possessed genuine merits as a writer. The truth is, he possessed rare skill and was a literary artist, a master of his craft. He has sometimes been called by his admirers “the Yankee Maupassant.” Some have affirmed that he had a special faculty for portraying the humor and pathos of the lives of the poor and lowly. They say his pages are filled with the tragi-comedy of life, like those of Villon and Dickens. These statements are true to a limited extent. O. Henry’s pages do abound with the tragicomedy of life much as it appeared to Dickens and to François Villon. But of course O. Henry was not the peer of Dickens or of Villon, and the comparison must not be pressed too far. However, O. Henry derived most of his inspiration from the lives of the obscure and degraded, and in his stories there generally figure such characters as cowboys, clerks, ward politicians, city policemen, shop girls, factory girls, tramps, vagabonds, and all sorts and conditions of men. Of this class of society O. Henry wrote as if to the manner born: he knew it in its varied aspects. He saw the humorous side of the pathetic park bench-warmers and bread-liners; and his tender, smiling pathos mitigated and softened the hardship of their lot, thus enlisting our sympathy from the beginning. Where, for example, can one find a more laughter-compelling case, albeit pathetic, than that of poor Soapy, the park-bench vagabond? Soapy makes many futile attempts to get into the clutches of the law, so as to secure for himself comfortable prison quarters for the winter; but the police blink him and let him escape. However, one day, passing a church he hears the music of an anthem which overwhelms him with a flood of boyhood memories. He is deeply moved and resolves in his heart to turn over a new leaf and make a man of himself. He goes into the church and, by the very irony of fate, is arrested as a vagrant and sent to “the Island.” This story of “The Cop and the Anthem” is quite representative.

Another story typical of O. Henry’s method and art as a writer is his excellent story “The Rose of Dixie.” This is a story of an old Southern Colonel who undertakes to edit a magazine exclusively in the interest of Southern readers. The magazine, catering to the tastes of Dixie solely and laboring under the serious handicap of its editor’s sectional prejudice, fails to increase in popular favor and is soon confronted by financial disaster. So, to avert impending failure, the stockholders engage a periodical promoter, a certain Thacker, to swell the circulation and to establish their magazine on a sound financial basis. The Colonel’s pride is touched. He spurns the radical and questionable advertising plans of Thacker, at the same time hinting mysteriously at an important article on the philosophy of life in the editor’s desk, which if he could get the consent of his mind to print in his magazine, its success would be assured. At last the Colonel swallows his prejudice and decides at all hazards to print the debatable article. He has the title emblazoned on the cover page in glaring full-faced type, but the author’s name printed in very small type, almost illegible. That author was T. R., then President of the United States! The story incidentally illustrates a characteristic of O. Henry of springing a surprise upon his readers and making the point of the joke turn upon some trivial or local significance.

It is impossible, of course, in the brief compass of the present paper, to attempt an analysis of O. Henry’s stories; their name is almost legion. Still one may attempt a rough classification. For while it is true that O. Henry wrote numerous stories, he did not vary his types very much, there being a certain degree of sameness about his themes and his structure. Perhaps his dominant type is the surprise story, such as “The Rose of Dixie,” above outlined. A second type is the irony-of-fate formula, such as “The Cop and the Anthem,” also above outlined. A third class is composed of his cross-purposes stories, such as the fine story of “The Fifth Wheel,” or that of “The Gift of the Magi.” Indeed, the entire collection of Cabbages and Kings may be cited to illustrate the cross-purposes formula. A fourth type may be described as those stories exemplifying the inertia of human nature, such as the pathetic story of “The Guilty Party,” and “The Pendulum.” These four types are at least rather clearly defined. A closer analysis, however, would probably result in a more minute classification with the different groups shading imperceptibly into one another. Too many of O. Henry’s stories end in a trick, or a cheap surprise-a feature which makes them somewhat monotonous when read continuously.

It is quite natural to ask which is regarded the best of O. Henry’s two hundred and forty-eight stories. But this question is not easy to answer, because the very number appeals to such a variety of tastes as to make the personal equation an all-important factor in the decision. All depends on the individual. Even among those who have read the entire twelve volumes of O. Henry’s stories, no agreement would probably be found as to his best stories, so widely are the critics divided on this question. His stories, somehow, more than those of any other writer, seem to have this peculiar effect in the realm of criticism. However, perhaps most critics would vote “A Municipal Report” the best of all the stories written by O. Henry. This story is contained in the volume entitled Strictly Business, and deals with Nashville, Tenn. In this story the author introduces Rand and McNally’s description of Nashville after the manner of a Greek chorus, and presents a little tragic drama of Southern gentility. Incidentally he establishes the falsity of Frank Norris’s dictum that New York, New Orleans, and San Francisco are the only centers of romance in our American life. This story, by the way, brought down a storm of criticism upon its author’s head from the citizens of that Southern city, who resented the satire and implied criticisms of their State capital. If one were to attempt to select our author’s ten best stories, there would be more dissent than there is as to the choice of his best story. But it is interesting in passing to record the selection made by Mrs. Porter, O. Henry’s wife. Her choice included the following, in the order named, as the ten best stories her husband ever wrote: “A Municipal Report,” “The Fifth Wheel,” “A Lickpenny Lover,” “A Doubledyed Deceiver,” “Brickdust Row,” “The Trimmed Lamp,” “The Brief Début of Tildy,” “An Unfinished Story,” “Madam BoPeep of the Ranches,” and “Adventures in Neurasthenia” (rechristened by the publishers “Let Me Feel Your Pulse”). It is needless to remark that while this selection is not far wrong, it would certainly not pass unchallenged, and various substitutions would be made in the list, were it submitted to the critics.’

As has been pointed out, O. Henry’s range, while not very limited, was at the same time not conspicuously wide. To be sure, he shows a considerable variety of themes apparently, but in the final analysis they are comprised in a few groups. It was chiefly from the proletariat—the humble and obscure classes, the human derelicts that he sought the source of his inspiration, and it was this class of society above all others that elicited and aroused his interest and sympathy. The rich figure only to a very limited extent in his pages. To apply Lincoln’s famous saying to him, O. Henry must have loved the common people because he made so many of them. He had a varied and detailed acquaintance with this class of society. He knew the flotsam and jetsam of life, and he had seen it on the ranch and in the mine as well as in the congested districts of the metropolis. His interest and sympathy, moreover, were as broad and deep as his knowledge was intimate. Herein lies the secret of his superior use of local description and the color he imparts to the characters and incidents in his stories. Yet he tells us that he did not lay much emphasis on the principle of local color. In defiance of Flaubert’s dictum, O. Henry, on the contrary, used to say: “So long as your story is true to life, the mere change of local color will set in the East, West, South, or North. The characters in the Arabian Nights parade up and down Broadway at midday, or Main Street in Dallas, Texas.”

With O. Henry the effect was the chief desideratum, and this he succeeded in attaining to a marvelous extent. His maxim was, “Get your effect, and with God-or the critics-be the rest.” However, he paid but little attention to the conventions of his art. The truth is, he affected to disregard the accepted rules and conventions, and the three classic unities. But it is hard to reconcile his profession with his actual practice. For his technique seems to have conformed generally to those very conventions he affected to despise. But, after all, he was a born storyteller, and his vignettes are models of their kind of writing. He certainly deserves the credit of rehabilitating the short story, which had almost gone into eclipse with Kipling. Even the publishers had come to look with askance upon this form of narrative as encroaching too much on the rightful domain of the novel. Yet in his eight brief years of creative activity O. Henry removed the stigma from this genre, and compelled the critical world to recognize the short story as a distinct and independent form of fictitious narrative, though closely allied in structural principles to the novel. This remarkable achievement he was able to accomplish by virtue of his fertile invention, his exceptional originality, his perennial humor, his flashing wit, and withal his mastery of his craft. He possessed as valuable adjuncts to his equipment a quick observation, a light touch, and a rare facility.

O. Henry sometimes felt the limitations of the short story growing out of its essential pure objectivity. To overcome this, he had recourse to frequent digressions, so characteristic of his manner. An example in point may be found in his story “A Night in Arabia.” Here at one point the author desired to converse directly with his readers. So he makes a brief digression to deliver an admirable little essay on modern rich men, and with nice discrimination and delicate humor he observes: “The capitalist can tell you to a dollar the amount of his wealth. The trust magnate ‘estimates’ it. The rich malefactor hands you a cigar and denies that he has bought the P. D. & Q. The caliph merely smiles, and talks about Hammerstein and the musical lasses.”

Among the most valuable assets of O. Henry’s equipment as a writer of stories was his mastery of the vernacular. His language is decidedly racy and piquant, and his slang is extremely picturesque. His vocabulary teems with racy slang phrases and incisive expressions. His imagery is clear-cut, and possesses a real charm. This, to be sure, is not true of all his stories, but is especially true of his best work, such as The Four Million and The Trimmed Lamp. In The Heart of the West, in which the author exploits a new vein-the so-called “wild West”-he makes a slight departure in his diction from the standard he set himself in his earlier stories. Apropos of the language of this book, it has been said that the author makes his Texan cow-punchers talk like intoxicated dictionaries, old-fashioned negro minstrels, and the advance agents of a wild-west show. But this criticism is unjust and unwarranted. By way of imparting the suitable local color, O. Henry interlards his vocabulary with copious Spanish phrases, and his speech smacks of the soil-so much so, in fact, that it is likely to prove a handicap to those readers not familiar with the lingo of the cowboy and the jargon of the Western miner. At his best, O. Henry makes the living speech do his bidding and shows his complete mastery of it. This fact of itself is an element in his success as a story-writer. Expressed in chaste, classic English, his stories would strike the reader as rather commonplace, and would fail of their full effect.

O. Henry’s humor deserves a word of comment, for it is one of his salient characteristics. In the amount of genuine humor he has infused into his stories, he stands unapproached. Even his keenest satire he mitigates and mollifies with an infusion of his quiet, kindly humor. Indeed, he used to be acclaimed “the new American humorist.” Nor does his humor depend for its effectiveness upon his local color or his never-failing optimism. His humor is rather a peculiar type, somewhat like Kipling’s. It is not broad, like Mark Twain’s, but terse and trenchant and allpervading. It irradiates and enlivens his pages and fills them with a distinct charm and glamour, and, except in rare instances, never degenerates into grotesqueness.

In view of the great vogue O. Henry enjoyed in his lifetime, it is pertinent to inquire whether his fame is likely to continue. That he was an artist possessed of exceptional gifts, no one will deny. His constructive power, his technique, challenged the admiration of all-even of his severest critics. He is unsurpassed in his own domain of the short story. His output, while considerable, is restricted nevertheless to this one department. So he must stand or fall by his reputation as a story-writer. This naturally limits his chances of permanency. Moreover, while he wrote many excellent short stories which suffice to establish his primacy in this genre, his inspiration was not always sustained, and he produced much work of a local and transient character that is far below the level of his best efforts. Not a little of his work, it must be conceded, is journalistic and ephemeral, and this will probably not appeal even to the next generation. His extensive employment of current slang, already noted, will no doubt prove a clog upon his reputation and a hindrance to succeeding generations. Time will separate out and eliminate that portion of his work which from its very nature lacks the enduring quality. But there is a considerable residue that has in it the element of permanency, and this residue will endure. His best work, therefore, seems to furnish a sufficient foundation for his fame.

THE RANSOM OF RED CHIEF.

The first O. Henry story I read when I was 12 years old. Required by my 7th grade English teacher. Was sure I would be bored–but what a laugh with the ending.