In August 2019, The New York Times, prompted by a notion of Nikole Hannah-Jones, began its 1619 Project—an attempt to rewrite completely America’s history by considering the year 1619 as the real birth of the American nation. In the words of New York Times Magazine editor-in-chief, Jay Silverstein:

1619 is not a year that most Americans know as a notable date in our country’s history. Those who do are at most a tiny fraction of those who can tell you that 1776 is the year of our nation’s birth. What if, however, we were to tell you that the moment that the country’s defining contradictions first came into the world was in late August of 1619? That was when a ship arrived at Point Comfort in the British colony of Virginia, bearing a cargo of 20 to 30 enslaved Africans. Their arrival inaugurated a barbaric system of chattel slavery that would last for the next 250 years. This is sometimes referred to as the country’s original sin, but it is more than that: It is the country’s very origin.

Out of slavery—and the anti-black racism it required—grew nearly everything that has truly made America exceptional: its economic might, its industrial power, its electoral system, its diet and popular music, the inequities of its public health and education, its astonishing penchant for violence, its income inequality, the example it sets for the world as a land of freedom and equality, its slang, its legal system and the endemic racial fears and hatreds that continue to plague it to this day. The seeds of all that were planted long before our official birth date, in 1776, when the men known as our founders formally declared independence from Britain.

The goal of the 1619 Project is to reframe American history by considering what it would mean to regard 1619 as our nation’s birth year. Doing so requires us to place the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are as a country.

The thesis has promptly met with outrage by many of the country’s leading historians: Gordon Wood, Victoria Bynum, James McPherson, James Oaks, and Sean Wilentz. A letter to the magazine, framed by Wilentz and signed by those and other leading historians called the project “a displacement of historical understanding by ideology.” The historians demanded corrections.

Silverstein responded with a sort of concession: The 1619 thesis was not an attempt to rewrite American history, but meant to be considered as supplemental to traditional approaches to teaching of the country’s beginning. That concession is hard to swallow given Silverstein’s claim concerning reframing American history around the year of introduction of the first Blacks from Africa. Reframing implies change of some sort. When one reframes a picture, one changes the frame and discards the old frame. It is likewise with a historical thesis concerning some event: here, the founding of our country. Moreover, there is the clear claim that arrival of the first ships of black slaves “is the country’s very origin.” There is one conspicuous omission: that of the boatloads of white slaves—comprising mudsills and the superfluous from prostitutes, urchins, prisoners, the penurious, the Irish, and the parentless—that were brought into the New World prior to the cargo of 1619. Is it because they were white that they are they not part of the country’s original sin?

The implications of the 1619 Thesis are prodigious. No longer is the narrative centered on the Founding Fathers’ struggles for colonial liberation from the oppressive Mother Country. We begin instead with “country’s original sin.” The centuries-old struggle of heroic resistance and eventual liberation through triumph against oppression in war is now subrogated by primal guilt through original sin. Heroism is subrogated by guilt.

Anti-black racism, says Silverstein, gave birth to unexampled and abusive economic power, the failure of the electoral college, America’s “unique” food and music, failures of health care and education, America’s penchant for violence, the ever-widening gap between rich and poor, degenerative American slang, American injustice, and racial paranoia, and all such things began because in 1619, 20 Blacks were boated into Virginia. There is nothing, it seems, salvageable in such a completely corrupt system.

It is an intriguing story, which if true, invites us to cast into oblivion all subsequent accounts of the founding of the United States. Anti-black racism, not heroism, is at the core of America’s story.

The thesis, however, suffers from one incommodious defect: It is scandalously vacuous.

Hannah-Jones, an African American who thought up the thesis, proudly vaunted that with the launching of the 1619 Thesis, sales of New York Times Magazine went, as it were, through the roof. “They had not seen this type of demand for a print product of The New York Times … since 2008, when people wanted copies of Obama’s historic presidency edition.”

There is historical revisionism and then there is Historical Revisionism—the sort of revisionism that bids us to forget all that we thought we knew and to begin anew. Is this instance of Historical Revisionism earnest or is it “all about the Benjamins”?

It goes without questioning that Silverstein and Hannah-Jones have profited monetarily with publication of such a draconian thesis. Draconianism is today what drives radical racial revisionism and the Dracos, to them, are all those Whites who are not supportive of the sort of ultra-leftism that demands wholesale self-hatred and nation-hatred.

Yet I scarcely think that Silverstein and Hannah-Jones are among the penurious in the gap between the rich and poor. To help to alleviate the problem of the haves and the have-nots, does Silverstein—as editor-in-chief certainly makes a handsome salary and probably “suffered” a bonus with the through-the-roof sales—donate the lion’s share of his hefty salary to America’s poor or to programs aimed to narrow the rich-poor gap? He and Hannah-Jones doubtless benefit handsomely from such a system, inveterately rooted in white hatred.

What follows from the 1619 Thesis?

It seems that all Whites, not buying into their thesis, are to admit their primal guilt and deracinate all American history rooted in the Founding Fathers’ myth.

Yet what is to become of white primal guilt?

It seems, given Silverstein’s bleak depiction of today’s America, that Whites can either wallow in their irremediable guilt or they, to eradicate their primal guilt, can destroy the system and begin afresh.

It is most inconvenient that neither Silverstein nor Hannah-Jones proffer an answer. That is distressing, for given the decrepitude of our country, America is despairingly in need of answers from its wisest citizens. Given that they have disclosed that the soul of Americanism is not love of liberty and championing of human rights, but instead white hatred and deep-rooted guilt, we are now certainly in need of their providential guidance, their providential wisdom.

Silverstein and Hannah-Jones conveniently seem to forget that it is because of the valiant deeds of the Founding men, and the women behind them, we are at place where and a time when we can entertain and discuss radical and vacuous theses like the 1619 Thesis. The problem today is that such discussions are rarely rational. Emotive language—fraught with pomposity, metaphors, and hyperboles (consider Silverstein’s “paean” for America)—predominates in such discussions to such an extent that complaints and demands of the country’s leading historians are merely overpassed. Vacuousness, in vogue today, is as reasonable as rationality, and it does not hurt to sell a few newspapers or magazines in the process.

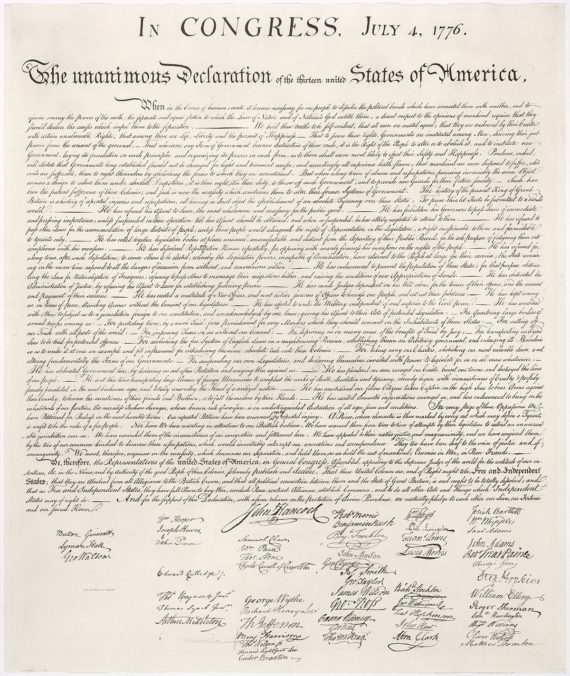

The signers of Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence signed off on the equality of all men, black men included, so the obsolescence of slavery was merely a matter of time. Most signers, I believe, were aware of that.

Sentences have implications. Those sentences which the 1619 Thesis comprises, I firmly assert, are inflammatorily dangerous not only because they invite wholesale revolution, but also because they do more to inflame racial tensions than to heal racial wounds, which require time to heal. Continued self-flagellation at some point becomes absurd. It is time to advance.

The equality of all humans articulated in Jefferson’s Declaration was not Jefferson’s creation, yet it was a new concept and certainly not free of ambiguity. Slavery has been extant for millennia, and it still exists in pockets of the globe. Moreover, it is not exclusively a matter of Blacks being slaves to Whites. The first black slaves in America were shipped to St. Domingo by Spaniards and auctioned for sale in 1503. Moreover, it was and is not merely enslavement of Blacks by Whites. Yet it has only been with the Enlightenment thinking of Jefferson’s day that people began to entertain seriously human equality. The Founding Fathers signed off on that equality, even if not all were convinced of its truth. They made it possible that thesIs, aimed at destroying their sublime thoughts and prodigious efforts, could be entertained. It is astonishing that Silverstein and Hannah-Jones fail to see that, though perhaps they do, and merely do not care. They have, of course, been encouraged in their foolishness by an ignorant public, thirsting for scandalous farcicality—a farcicality that has earned Hannah-Jones the Pulitzer Prize. It is time to note that that “prize” has itself become farcical and should be disprized.

I am sure that some people will misinterpret this, but it seems to me that the whole idea of the 1619 Project is that the country is supposed to revolve around 13% of the population.

A fair assessment.//

No sir. The point is to continue the struggle against a moral code. 1848 saw the introduction of a theology by “intellectuals” who made it their purpose to destroy western civilization and Christianity.

The “opiate of the masses” is being displaced by a theology that has never been able to provide the basic necessities of the society it served…but to be fair, the only reason Christianity or western civilization prospered is because “those people stole all the land”. Sarcasm implied for those who don’t get sarcasm.

1619 is just another lie piled upon the lies before it. Certain powerful groups support these idiotic lies because the lies keep their bulldogs chasing their “enemies”. Unfortunately, bulldogs turn on masters…it’s just the nature of bulldogs. Apologies to all the bulldog lovers out there, who, imbecilically, keep bulldogs. “She was such a sweet bulldog until she crossed the border and killed a bunch of people.”

This internet is revealing all of the lies. Soon, harvard researchers will discover the 14th Amendment which disenfranchised White Southern males and the 15th Amendment which gave blacks the right to vote in the South SINCE WE KNOW BLACKS WERE ALREADY VOTING UP NORTH BY THE DOZENS. Actually, dear reader knows blacks weren’t voting up north…

Sadly there are several generation of Americans who believe that the institution of slavery was not seen on this earth until 1619 in Virginia.