We live in a regime with an industrial output of lies about Southern history, so we should let our forebears speak for themselves whenever we can. I have been reporting on little known Southern books and here is another.

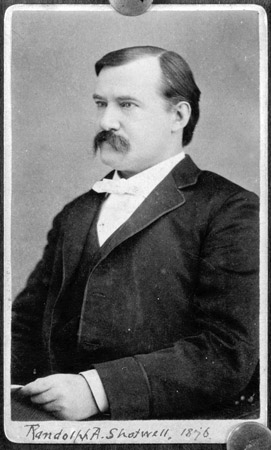

Randolph Shotwell in the 1880s put together some materials for his an account of his extraordinary life, using his diaries, letters and other papers, and recollections. These materials were published in 1929 by the North Carolina Historical Commission as The Shotwell Papers, edited by J.G. deRoulhac Hamilton, founder of the priceless Southern Historical Collection at Chapel Hill.

When The War broke out, Shotwell was a 17-year old student at an academy in Pennsylvania. The Yankee preacher who had been entrusted with his money by his North Carolina family refused to let young Shotwell have it. He set off on foot to return to Dixie with almost no money and inadequate clothes and shoes. People traveling South without permission were being arrested and sometimes murdered by mobs.

After much vividly described hardship he reached the heavily patrolled north bank of the Potomac. After several tries he finally was able to get across the river—under fire. Shotwell had vowed to join the first Confederate unit that he met. It turned out to be the 8th Virginia, which meant that he would eventually become part of Pickett’s division.

Shotwell wrote well. If he had not belonged to a society that was destroyed he might have become a significant writer, but his life’s work is mostly journalism and private observation. He was extremely literate and well-read.

He had strong opinions. While serving as a soldier, He is brutally frank about the hardships of Confederate soldiers and the shortcomings of Confederate policy and administration. The same approach to Republican atrocities during Reconstruction would land him in prison.

During the famous charge at Gettysburg, Shotwell was cited for having spontaneously formed men into a flanking formation as they withdrew down the ridge. He became an officer. During the Wilderness campaign in 1864 he was captured while scouting inside Union lines. He spent the rest of the war in the pits of hunger, disease, and exposure that were prison camps for Confederates. Despite many inducements he refused to take the oath to the U.S. government and was late in being released.

The most interesting part of Shotwell’s career is in Reconstruction. Returning home he founded on a shoe string a newspaper at Rutherfordton in Western North Carolina. For most of the rest of his life, like so many Southerners, he eked out a bare existence, in his case with unprofitable newspapers.

Shotwell had a distinctive biting style recognized immediately by readers. He frankly exposed and condemned the atrocities committed against law and order and the conservative population by the Reconstruction Republicans. His target was white Republicans, not the freedmen. He also called to account leaders on his own side for what he considered their wrong moves.

In 1871 the Republicans passed a “Ku Klux Bill” while the press promoted an exaggerated picture of violent rebelliousness in the South. In preparation for Grant’s re-election campaign this law was used, in an event of Reconstruction that has seldom been noticed, to remove conservative community leaders. Shotwell, with many others, was arrested in the night, not even with a change of clothes, and taken in chains to a court 200 miles from home, depriving him of counsel, family, and friendly witnesses.

The same happened to people all over the South, more than a hundred from North Carolina alone.

On perjured and hearsay testimony from North Carolina scalawags and carpetbaggers, in a kangaroo trial backed by soldiers, he was sentenced to six years hard labour among the criminals at a prison in Albany, New York. There was also a fine of $5,000. If he had had even a fraction of that money he could easily have bribed his way out with the corrupt officials. Then and while in prison he was repeatedly urged to secure freedom by giving evidence against others, which he refused.

The Republican policy worked. While Grant lost the Northern white vote to anti-war Horatio Seymour, he won by the electoral votes of the Southern states where the army controlled elections and the black vote was cynically marshalled for the Republicans.

Shotwell did not serve the entire six years and he was finally pardoned. Reconstruction was gradually loosening in Northern opinion. A number of Northern officers for whom he had done kindnesses while they were prisoners rallied to his defense. He won admiration for his humane management of the prison hospital, equally kind to criminals and political prisoners, blacks and whites.

He got no support in prison from his mother’s Yankee kinfolk who demanded that he repent of his sins, having been turned into a criminal by being raised in the South.

He returned home to a sparse existence. In 1884, his fellow ex-Confederate Governor Scales appointed him State Librarian, which would have eased his poverty. But he died at the age of 40 before taking the post, his early death no doubt the product of the hardships of prison.

His story is only one of thousands who sacrificed greatly and honourably in defense of the South.

Great story of a man I knew nothing about, thanks Professor Wilson. I love everything you write.