A review of The Southern Tradition: The Achievements and Limitations of Southern Conservatism (Harvard, 1994) by Eugene Genovese

The notion of a Southern political tradition can be understood as conservative, complete, and consistent with its roots. Eugene Genovese’s The Southern Tradition poignantly articulates these qualities from the perspective of a Marxist gone conservative—a Southern conservative, indeed. Elucidating Genovese’s understanding of “Southern conservatism” will shed light on what like-minded conservatives mean when they say that the present Gingrich House conservatives are not their “type of conservatives.”

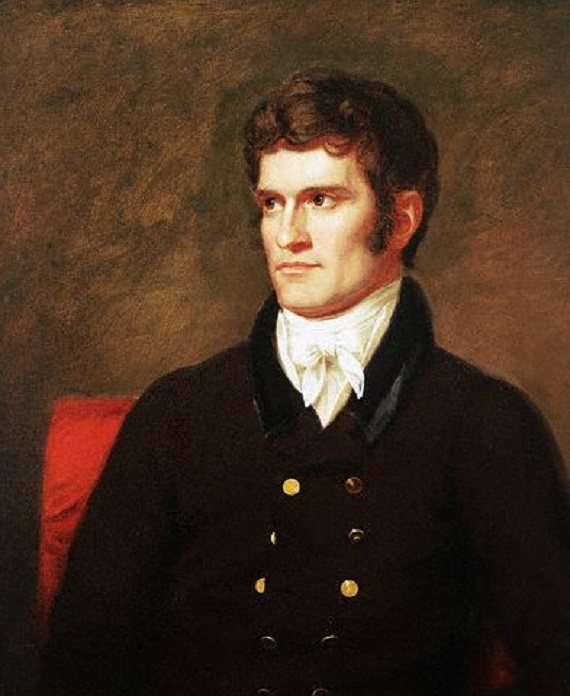

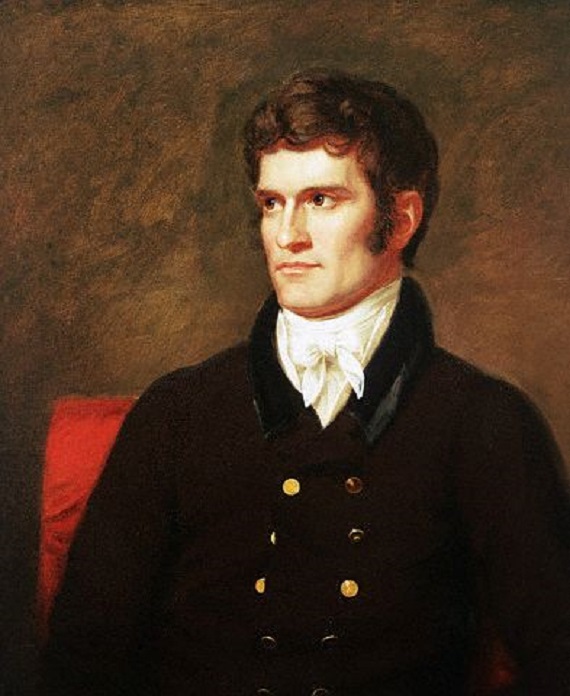

Southern conservatism, according to Genovese, is closely related to “transatlantic traditionalism. Conservative European philosophers like Edmund Burke were heroes to the Southern conservative intellectual movement that gained national influence in the 1930s under the name, “Southern Agrarians.” Briefly, transatlantic traditionalism viewed political problems as religious and moral, hence opposing any attempts at secularization. Moreover, it rejected the idealism of an egalitarian society, finding pursuits of classlessness as invitations to tyranny. While Burke was specifically responding to the French Revolution, conservatives today cite the long history of “egalitarian regimes” that promised absolute class equality only to deliver mass murder. Nevertheless, prominent figures of early Southern conservatism, like John C. Calhoun and John Randolph of Roanoke, were far from monarchists or aristocrats, for they believed themselves to be republicans, as those who believed in the sovereignty of the people, not popular rule; “constitutional” democracy, not “absolute” or “numerical.” “We call our State a Republic—a Commonwealth, not a democracy,” stated Calhoun. “It is a far more popular Government than if it had been based on the simple principle of numerical majority.

To these Southern “republicans,” representative democracy, rather than “direct” democracy, was premised on the innate inequality of humans as individuals, and thus, a social hierarchy inevitably developed based upon the value of these natural inequalities. It is important to note that this notion of “inequality” was never intended to use race as a criterion, but ironically became so under scientific progressivism—distrusted and viewed with contempt in the South—which buttressed racist rhetoric with facile scholarship and statistical “credence.” (Today, The Bell Curve, in some way, has reignited this venue of debate.) It was specifically this hierarchical society which the Southerners evolved from and wished to preserve that gave the region its brand of conservatism, altogether unique from the social stratifications found in the North where big industries and a free- market labor lie in stark contrast. Agrarian intellectual M. E. Bradford averred, “Not religion but the cult of equality is the opiate, of the masses in today’s world—part of the larger and older passion for uniformity or freedom from distinction.” Therefore, “Equality as a moral or political imperative, pursued as an end in itself—Equality, with the capital ‘E’—is the antonym of every legitimate conservative principle.”

Genovese, furthermore, delineates the religiosity of the progressive, liberal North, and the Old South’s defense of mainstream Christianity. Having relinquished its Christian orthodoxy since the beginnings of nationhood, the North, in the eyes of conservative Christians, had receded into heretical deviancy. The Unitarianism that permeated northern institutions, like Harvard and influential churches of the northeast, was the South’s evidence of the North’s moral and religious recidivism. Some northern churches were as extreme as to abandon the doctrine of original sin and human depravity for a progressive view of God and mankind. Theologians like Friederich Schleiermacher and Adolf von Harnach attacked church dogma, and radical theologies like Arianism and Socinianism undermined established beliefs. Other churches even went so far as to not require a fundamental Christian conviction that Christ was Savior.

By contrast, Southern conservatives, who viewed politics through moral and religious lenses, found God to be real with an inscrutable will, and “whose commands must be obeyed, no matter how deeply they may offend ordinary human sensibilities.” Their faith was grounded on local judgment and nonscientific discernment. This carried over into their literal reading of the Bible, allowing the individual to come to an understanding of scripture based on “community-grounded prejudices and apparently non-scientific modes of discrimination,” hence without the encumbrances of progressive theologians and liberal theology that was contaminating the North. Concomitantly, Southern conservatives valued individualism. For the Southern conservative “Christian individualism,” attained through the Protestant Reformation, allotted the Christian the “right of private judgment,” yet the faith bounded this liberation with communal responsibility.

They embraced Scottish Enlightenment, which taught them to distrust “ideological nostrums,” and rely upon “Christian revelation” and “God’s providence in nature and human history.” These experiences would provide the bulwark for moral principles that would be used to guide the individual within society. Established upon the ideals that emerged from the French and Industrial revolutions,

“Renaissance individualism” gained little, if any, support from conservative traditionalists.

Differences in religious tenets provided a comparison of northern and Southern brands of Christianity. “As a divinely inspired elite, of moral Christians, the abolitionists proclaimed egalitarianism, but in actuality simply replaced the old elite with a new, making little significant headway for the general masses whose cause they purported to advocate.

Southerners understood God to provide varying amounts of “talents” to humanity, and intended for some inequalities, which naturally resulted in a stratified society. Property became the symbol of class demarcation, delineating the various social strata, and preserving moral and spiritual values. Ownership of property, however, was not to be centralized but broadly owned amongst communities in small and middle- sized groups. Ironically, after 1865, the South would find itself in the same predicament for which its predecessors wholeheartedly denounced the North at the start of the war: a society must have private ownership of property to sustain general morality and integrity. Having replaced the old system of slavery, the North, and eventually the South, succumbed to a free market system that over time stripped away the social relations necessary in retaining a working, living community. (Today, the unholy alliance between free-market libertarians and traditional conservatives is tartuffery, since the former opposes any controls, and the latter, understanding the errancy of man, advocates social boundaries dictated by elites.) In short, Southern, conservative Christians saw no possible reconciliation of the abolitionism, radical egalitarianism and the elitism with which these social “progressives” imposed their set of beliefs upon the slave states.

The 1994 congressional elections have placed a body of conservative Republicans-from the South, at that, who profess to uphold conservative principle-on Capitol Hill and into powerful decision-making positions, the implications of which go far beyond their small town constituents. Though they do measure up to some conservative traditionalist principles—smaller federal government and state’s rights-these Southern Republicans are enraptured in the polity’s edict for action. They lack fundamental understanding of their responsibility as elites for certain issues, unbridling the dangers of free-market capitalism, which Genovese’s traditional Southern conservatives had cautioned of before the Civil War.

Southern conservative philosophy and constitutional principles promote limited government, and Gingrich’s Contract with America is doing exactly that; but a realistic balance must be reached. The preservation of “traditional values” necessitates government to interfere, as least and as delicately as possible, in a society where the market heavily influences many social and economic outcomes. Genovese argues that Americans placed trust in similar lopsided political philosophy when electing Reagan, and, when disappointed with the results of Reagan’s optimistic view of humanity, advocacy of limitless material progress, and devotion to free-market/finance capitalism, “bitterly denounced its aftermath in the Bush Administration.” For what the Reagan administration represented, it can be correctly deduced that Reaganism embodied right-wing liberalism. “His radical individualism and egalitarianism represent much that Southern conservatives have always loathed.”

Eugene Genovese’s articulation of the Southern political tradition pertinently reviews American conservatism’s intellectual roots. Though a free-market capitalistic system seems to have been a bedrock of America’s conservatism, according to Genovese, its overemphasis partially belies the full history of conservatism, partially lost and partially diffused since 1865. The preservation of Christian orthodoxy and individualism; advocacy of representative democracy; broad ownership of property; and free-market economy bounded within limits of morality—these are the qualities of the southern tradition that seem lacking in today’s matrix of conservatism.

This piece was originally published in the 3rd Quarter 1995 issue of Southern Partisan Magazine.