The piece was originally published at A Memoir of the Occupation.

(In the old days, my grandfather said, the birthday of General Lee was commemorated with solemn ceremonials and a speech. The Sons of Confederate Veterans, of which I am a member, maintains this tradition. Were it ever my honor to do so, I’d deliver a speech along the lines below.

Please let me emphasize, though, that the views below are entirely my own and not those of the SCV.)

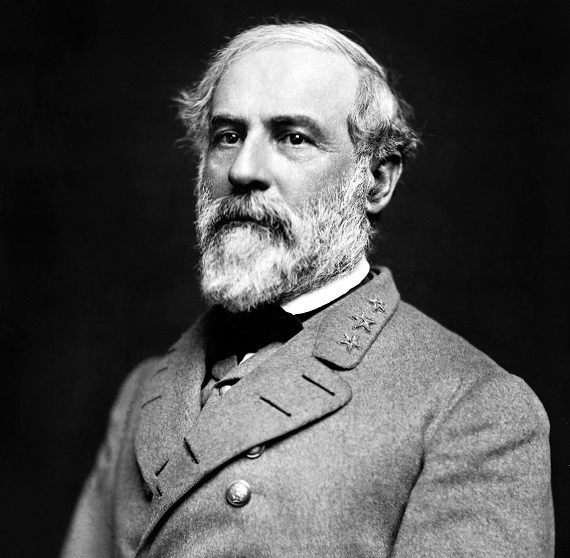

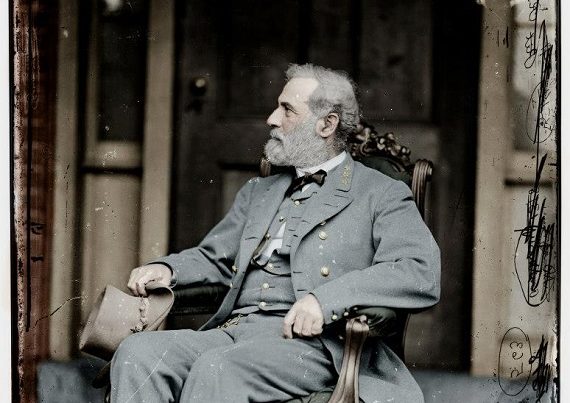

Good evening. It’s an honor, far more than I deserve, to speak on this, the 219th birthday of General Robert E. Lee.

The voters of the Old Dominion exercised that most sacred right of a free people last November and chose a CIA agent as their governor. She — pardon me if the pronoun is incorrect — replaced the one-time former co-CEO of The Carlyle Group, the shadow bank of choice for the defense industry. Not that party affiliation is at all important, but the private equity person was a Republican, Glenn Youngkin. Born in Richmond, he’s an entirely predictable Republican type with the sculpted hair and toothy evangelical grin that can’t hide the utter lack of substance behind it. His replacement, the spook, is a blond Democrat woman whose name I don’t recall and don’t care to look up. She defeated one Winsome-Searles (her first name eludes me), the Carlyle creep’s lieutenant-governor, a Jamaican ex-Marine once lauded by Fox News/Prager U “principled conservatives” as a Strong Republican Woman with Gun. Just like Harriet Tubman. Well, there’s a reason they’re called the Stupid Party.

Youngkin, as a sort of swan song, appeared at the federal Capitol in the imperial city. The occasion was some sort of American ceremony marking the replacement of a statue of General Robert E. Lee with that of teenage “activist” of whom no one has ever heard. Hakeen Jefferies, a Democrat leader in Congress, expressed delight that Virginia was no longer represented by “a traitor who took up arms against the United States to preserve the brutal institution of chattel slavery.”

Well bless your heart, Hakeem. There’s no point in being angry at either him or the intern who generated his wretched remarks from ChatGPT or whatever it’s called. It is safe to assume that Youngkin, probably dumb enough without the help of AI, applauded Hakeem’s declaration of idiocy, reiterating as it does the unassailable doctrine of the despicable, cowardly, treacherous, traitorous and altogether vile Republican Party. And Hakeem, or the intern, or ChatGPT, has a point: Robert E Lee does not represent Occupied Virginia, the Old Dominion occupied by the worst people in the world: private equity titans, intelligence agents, the Yale and Harvard lawyers and lobbyists under whose guidance the Federal Register has metastasized to over 90,000 pages – every single regulation created to privilege private equity, spies and their paymasters. I’m sure some Republican activist created one of the usual “that’s not who we are” bleats, reminding unaffiliated minority voters that the GOP is the party of Lincoln and Grant.

And we concur wholeheartedly. No, Robert E. Lee has nothing to do with you Republicans, and I personally wish nothing to do with you either. Virginia, a bedroom for the amoral bounders who constitute the State, does not deserve to be represented by General Lee. So I, for one, am happy that his statue is no longer in the cathouse of the U.S. capitol. Just as I am pleased that U.S. military bases no longer bear the names of Confederate generals. You are not who we are, and I do not want our brave men soiled by association with your mercenaries, which as far as I can tell have yet to fight in a war in actual defense of the American people — whatever the “American People” may be these days. I hear Vivek, running for governor in Grant and Sherman’s home state of Ohio, has a powerpoint breaking it all down.

Because we fought against you. We of the South. And if I may further quote the old song: I despise your glorious union, your striped banner, your nasty eagle, all of them dripping with the blood of Southern soldiers, their wives and sons and daughters. I’m glad we fought against you, and I only wish we’d won.

I am, like all of us here, the descendant of Confederate soldiers. My people been here a while. We were in Virginia way before Hakeem, and the private equity bozo, and the spy, whatever her name is. So there’s a lot of us. I’ve identified 32 Confederate soldiers on my mother’s side, 27 on my father’s. That includes cousins and second cousins. A not-inconsequential number served in the Eastern theater, and a similar number in the West. The closest in blood is my great-great-grandfather. He saw General Lee at least once. It was Maryland in September of 1862, his regiment was on the march, General A.P. Hill’s force assigned the capture of Harper’s Ferry. General Lee stood on a rock on the roadside watching them pass. The colonel of the regiment described General Lee as the most noble man he had ever seen.

In 1861 my great great grandfather was a small farmer in Alabama. He was twenty-four, married, one daughter. He did not own a slave. But in April 1861, one month after Lincoln took power, he and his brother enlisted in a regiment organizing in Montgomery. The term of the enlistment was “for the duration of that war” – or death, whatever came first. It was the Southern regiment to do so.

The regiment took the train to Richmond, Virginia, which had replaced Montgomery as the capital of the Confederacy. The first time many of the freshly-minted soldiers had crossed the county line, much less the border of Alabama. And for many, it would be the last time they saw the land of their birth.

In Richmond, the regiment was incorporated into the army commanded by General Joe Johnston. My great great grandfather and his brother fought in its first battle: Williamsburg on the Peninsula, where Joe began his Confederate career as he ended it: a backwards movement to the capital. To the very gates of Richmond, pursued by that long-suffering, hard-luck yet proud army created by George McClellan: the Army of the Potomac.

Johnston turned to face McClellan at Seven Pines, at the very gates of Richmond. When twilight descended on the bloody chaos of battle, the crones pulled a thread, or fate intervened, or perhaps Providence or the cunning of history: Joe Johnston was severely wounded, shot in the shoulder. The next day Jefferson named his replacement: his military advisor, Robert E. Lee. Lee’s record so far had been less than impressive: beaten by William Rosecrans in West Virginia and derided as the “King of Spades” by soldiers detailed to dig defensive works around Richmond. Some called him “Granny Lee” for his white hair.

You will assume command of the armies in Eastern Virginia and North Carolina, and give such orders as may be needful and proper, Davis wrote. And so was born the Army of Northern Virginia, which under General Robert E Lee would join in the muster of the immortals, the finest armies of all time. The Imperial Guard of Napoleon Bonaparte; the fearsome Macedonian heavy infantry of Alexander. The warbands of Alfred the Great who rid England of the Northmen. The three hundred Spartans who with King Leonidas died holding the passes of Thermopylae against the Persians.

For four years he followed Marse Robert: Seven Days, Second Manassas, the capture of Harper’s Ferry. A fast march to Sharpsburg and a posting in the Bloody Lane, just in time to defeat a Union attack. At Salem’s Church his brigade routed Sedgwick, hurrying from Fredericksburg to salvage “Fighting Joe” Hooker’s Army of the Potomac from the wreckage of Stonewall Jackson’s flank march. My great great grandfather and his brother were General Lee’s men: scarecrows in tattered grey or butternut, shod in square-toed brogans liberated from a dead Yankee, hard and wolvish men who inflicted on the United States Army the most crushing defeats it has yet known.

The brothers last saw each other on July 2, 1863. Their brigade was in Longstreet’s Corps, in the attack across the Emittsburg Pike when – not once, but several times – they broke the Union line. But as was always the case, reserves insufficient to convert to break to a rout. A cannonball struck his brother’s foot during the attack, and my great great grandfather was captured.

My great grand-uncle endured three amputations: first the foot, then the leg at the knee and finally the upper thigh as gangrene set in. But he survived. There’s an application for a prosthetic leg in his record, which also states he was six feet tall with auburn hair. It also records that he carried the message from General Lee’s headquarters to Richmond with the report of Stonewall’s death. He raised my great grandfather after the war, and told these stories to my grandfather, who told then to me.

My great great grandfather escaped his Union captivity and made his way to Virginia. So he was there in 1864 when Grant, the hero of Vicksburg – after ten tries and even then only with the aid of General Hunger and General Terror — led a new Army of the Potomac, 120,000 strong, over the Rapidan into that tangle known as the Wilderness. The idea was to roll through to Richmond and God help General Lee and his army of 60,000 should it dare get in the way. Grant and his cronies from the West were confident after their triumphs against Pemberton in Vicksburg and Bragg at Chattanooga. They smirked at counsels of caution from General Meade and his officers. I don’t maneuver, Grant said.

We know what happened next, don’t we? General Lee and his veterans were ready and waiting. The Army of the Potomac was destroyed in the Overland Campaign: the tactical genius of General Lee, the ferocity of the Confederate soldiers, the liberality with which no-maneuver Grant hurled his legions in the general directions of the Confederates. Seventeen thousand in the Wilderness, eighteen thousand at Spotsylvania. At Cold Harbor, the savior of the Union threw musicans scraped from the Washington garrisons at the Confederate works: 7000 casualties in 15 minutes.

But the boss didn’t mind. I won’t give up Grant, Saint Lincoln says. He fights. And that is how he fights. Grant, who H.L. Mencken says had “the imagination of a respectable hay-and-feed dealer” was no Napoleon but did have a sort of boozy grasp of the iron law of attrition: unlimited resources will all ways conquer limited resources, provided there’s a commander who isn’t overwhelmingly troubled by casualties. And even then the whole world wanted to be American and was willing to fight for that august privilege. One fourth of the U.S. Army was foreign born by 1864 and more on the way as Lincoln’s agents drag greenbacks through impoverished villages in Germany and Ireland. And there sits Grant, the quiet man from Galena, sitting on a stump far behind the lines and whittling. Imperturbable, although it’s said he cried himself to sleep after Bobby Lee smacked hum around on the first day of the Wilderness battle. He’s back to himself again, calm and quiet, sitting on his stump, whittling away. Else he’s up the James River on a gunboat, drunk.

It’s not well known, but by the time the armies faced each other at Petersburg, the Army of the Potomac was wrecked. Nearly 60,000 casualties in the Overland, the size of Lee’s entire army; the masses of conscripts and replacements refused to attack Confederate trenches. My great great grandfather’s regiment was in Malone’s Division then. General Lee’s shock troops; William Mahone was a railroad engineer who knew the ground intimately and he used it to deadly advantage. They easily routed and defeated the Union at the Weldon Railroad, Jerusalem Plank Road, the Crater.

The soldiers of the Army of Northern Virginia were confident. They’d taken the measure of this new iteration of McClellan’s army. Their confidence in General Lee was complete. Lee had taken the measure of Grant (Mencken says Grant “quailed before Lee’s sardonic eye” at Appomattox). Just as he had taken the measure of McClellan, Pope, Burnside and Hooker. His men were confident in their ability to whip Grant.

But General Lee understood the math, and had always understood it. He knew that to defend Richmond, required by Jefferson Davis, meant that Grant, with his monstrous army and unlimited pool of replacements, would eventually extend his lines to envelop the capital – and he would pay any price in blue-clad corpses to do so. Eventually Richmond would be under siege, and like Vicksburg, fall to hunger and terror.

I’ve often wondered if my great great grandfather, in the Petersburg trenches, on the parapet of a defensive work, as the lush golden haze of Virginia autumn gave way to the freezing rains and sleet of winter, also grasped the mathematics of it all. How many Yankee campfires for every Confederate? Ten? Twenty? Fifty? If he realized the relentless will-to-dominate of the machine knocked together by Grant ? A quartermaster in the Mexican war, Grant may have had the imagination of a “respectable hay and feed dealer” and the “virtues of a police sergeant” (Mencken) but he was a master of moving A to B to ensure C can destroy D. Because that was the way of it now. General Lee’s veterans saw smoke and flame rising from farms plundered by the “liberators,” heard “Hail Columbia” rising from the Northern trenches, well-fed tongues greased by the ration of cheap whiskey ration. And perhaps my great great grandfather saw, or understood, that a New Age was dawning, a new world rising from the ruin visited upon the South: the triumph of Quantity over Quality, of industrial capacity, of logistics. The age of Capital, of the Factory, of Free to Choose whereby one chases personal self-interest and plunder without the old limits of history and duty and tradition.

Did he regret that day in May 1861 when he said farewell to his wife and child, his aged mother, when he signed his name on the muster roll? Did he wish that after escaping Yankee capture at Gettysburg, he had instead crept home, gathered the wife and kid, and snuck off to California where he might re-invent himself as a new American?

Perhaps he did. But I suspect his spurned those considerations with contempt, assuming he even had them.

In 1861 my great great grandfather suffered from a tubercular condition. Nevertheless he enlisted – for the duration. In early 1863, after Sharpsburg, he obtained a thirty-day furlough on medical grounds. He could have applied for and very likely would have obtained a medical discharge, and remained home without shame or dishonor.

But he didn’t. He had sworn an oath: victory or death.

It ended in April 1865. By then the Army of Northern Virginia, the most magnificent fighting force ever mustered on American soil, was a mere 8,000 effective rifles. Barely a skirmish line against 150,000 Federals. And it was then, only then, that the Union managed to break Confederate lines. With a superiority of 142,000 troops – and Southern officers distracted by a fish fry.

General Lee would have preferred dying at the head of his ragged and starving troops in one last desperate charge. And indeed, at least twice during the Overland – the Wilderness and Spotsylvania – he tried to lead such a charge, only to be restrained by his men. Better death than surrender to those people. But who would care for the women, the children and the old, given the ruin Sherman and Sheridan’s hordes were visiting on the South?

So he clad himself in his finest uniform, a red sash and his finest sword and presented himself to the avatar of the new age.

Over 2000 men served in my great great grandfather’s regiment from 1861 to April 1865. Less than 80 men and two officers surrendered at Appomattox. They tore their worn and bullet-flayed banners into shreds rather than letting them fall into the hands of the Northerners.

My great great grandfather was not among them. He died on January 22 in Howard’s Grove Hospital in Richmond. The cause of death: phthistis, an old name for tuberculosis. The conditioned that worsened over those four years of blood and hard marching, dust of long roads through Maryland and Pennsylvania and Virginia, damped by the blood of bootless feet, a handful of parched corn and a finger’s length of pig-far for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Four years of fixing bayonets and forming into battle line, emerging from the cover of a hillside or a wood. A double-time march over a gentle field or a rolling pasture, breaking into a trot as the line took on a deadlier shape, a spear charged with furious energy toward a blueclad host that was not who we are, was never who we are and who never would be, well-clad lines of well-fed boys who should not be on these lands where our fathers are buried. And then erupts from the hearts and stomachs and souls of thousands, or tens of thousands: that foxhunt yip, that banshee howl (as Shelby Foote described it), a sound like that of an enraged cougar or a wolf: the terrible and magnificent Rebel Yell, the war-cry of the Southern soldiers.

A war-cry now as lost as Atlantis, a sound that will never again be heard this side of Valhalla. It died with the Southern soldiers, like the old Republic. And like the old Republic, buried at Appomattox.

My great great grandfather is buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Petersburg. A few years back I found his grave and marked it with a headstone. The government of the victorious nation would prefer he be forgotten. Doubtless some developer is eying Oakwood’s acres and planning a condominium knocked together by Mexican laborers with Chinese materials, an all mod cons luxury high-rise to to house Virginia’s new population of CIA agents and private equity fund managers. Americans still about the great work of Lincoln, I guess: bestowing the blessings of freedom on all the peoples of the world, a task made far easier by simply bringing them here.

My great great grandfather died with the conscious of duty faithfully performed, unsurpassed courage and fortitude, and knowing like the Spartans of Leonidas, he kept his vow. That vow to fight for the duration, or die trying. Maybe it was initially made to an abstraction of “government,” the newly independent State or the nascent Confederate government. But soon enough it became a vow to a living man: General Lee.

“Such was the love and veneration of the men for him that they came to look upon the cause as General Lee’s cause,” Charles Marshall of his staff once wrote. “and they fought for it because they loved him. To them he represented cause, country and all.”

The loyalty of those Southern soldiers to General Lee was a ferocious thing, a summoning from the depths of ancestral blood and memory the devotion and love of the old Irish or Anglo-Saxon warbands to their chieftans, their high kings. It had nothing to do with Principles, with Constitutions, and least of all with the squalid disgrace and dishonor of democratic politics. It was a loyalty of the old ways: to a man who had proved himself worthy – a warrior, a man of virtue like a Roman of the Republic, a man of arete like Agamemnon. A man who carries the image of a people. Not an abstraction like “American,” but a man bound to the soil of a specific place, the land which holds the graves of ancestors, a land that bears the memories, the myths and legends, griefs and joys of the past: all of the strange and mystical elements that define a people.

No other man born in North America has ever commanded that devotion, and given the entire American system is designed to crush such individuals, ever will again.

Which is why the latest round of desecration, the astroturfed “racial reckoning” that began with the death of George Floyd they paid particular attention to the statues of General Lee in Charlottesville and in Richmond.

It’s not necessary, I think, to review what they did. Cheered on, let’s not forget, by the Republican Party, eternally false and cowardly. And let us not forget that it was done with malice. Gleeful malice and petty viciousness revealing that if nothing else, the Republicans cleave to the traditions of such despicable specimens as Charles Sumner, Thaddeus Stevens and Benjamin Wade, the architects of the Reconstruction schemes that robbed the South blind, impoverished it for generations – black as well as white. Like the Abolitionists, the Radical Republicans hated white Southerners far more than they cared for blacks, who the victorious Billy Yanks, knapsacks stuffed with Southern loot, certainly did not want in their quaint New England villages.

Shelby Foote once spoke of a pact between North and South. The triumphant Americans would permit us our statues and our memories. We, in turn, would be loyal servants of their Empire. We would fight in their wars and work in their factories and salute their flag and shrug it off when they mock us. And there was, I think, a brief window in which the pact worked. The Northerners themselves grew increasingly disgusted at the petty viciousness and outright robbery of Reconstruction. Time softened hard memories. It seems that every issue of Confederate Veteran, published by the United Confederate Veterans from 1893 to 1832 contained a letter from a Yank in Michigan or Ohio or Maine recalling from kindness from a Rebel, or an old Confederate remembering an episode of Yankee decency.

Well, the United States of America has chosen to boldly and proudly renounce that pact. The new strategy is, it seems, to deride Lee as a “loser,” as an incompetent commander relative to Grant, the American Ulysses, who has been remade as some sort of hero of civil rights. I noticed this in 2020 or so, when “conservative” websites began singing the praises, all in the same key. Grant the Great Captain, devoted to equality and blessed with a profound love for blacks, the smasher of the KKK. Grant the Republican, of course: another stupid political ploy to attract minority votes. Graduates of PragerU and readers of Claremont Institute twaddle revealed themselves: Confederate monuments are “participation trophies” for “traitors” and “terrorists” and (of course) “racists.”

Yeah, okay. But tell us, please. All you patriots. How is that Grand Republic working out for y’all?

It’s working out exactly as General Lee said it would: aggressive abroad and despotic at home. Devoted to radical egalitarianism, self-anointed as God’s terrible swift sword, claiming for itself the power to remake reality in its own image and the right to take what it wants. The rest of us suffer what we can.

Freedom, progress, democracy; “muh rights” meaning perversion unrestrained; a warmongering breaker of treaties and duplicitous to a degree never seen in world history. The blessings of Union victory predicted by not just General Lee, but General Cleburne, Edward Ruffin, Robert Dabney and countless others.

The South, let’s remember, fought to separate itself from this vileness. It fought to be left alone. And that is unacceptable to the Beast in Washington. And so we see why General Lee remains such an offense.

Man must suffer to be wise, Aeschylus said. And in the brutalities and sufferings of the war, we gained something. Rather, we became something: a people. We became the Southern people. In General Lee’s march columns, in his battle lines, the English, Irish, Welsh and Scots who had populated the South prior to the Revolution became a people. An ethnos. One of the unique peoples to emerge from the British Isles. Not the oldest, not the mightiest, not the most brilliant, but with our own particular gifts: music, language, words.

And courage. Our ancestors enlisted as Georgians and Mississippians and Texans and Virginians. Under General Lee’s command, in his columns and battle lines, we became Southerners. We know who we are.

I’m not so sure about the rest of the nation. There seems some confusion about what exactly is an “American” but I’m fairly confident we’re not welcome. Well, bless your hearts.

The Confederate soldier did not fight for conquest, to expand the reach of slavery, much less to impose “systemic white racism” or hurt trans kids. He fought to defend his people and he fought in defiance of Northern arrogance. He fought because they were down here; he fought because he saw that they meant to rob him of everything he held dear: not wealth and property, but his very soul. To replace the old ways and the things learned from the old folks with a progressive imperialist Gnosticism, to poison his memory, to make he and his posterity despise and reject those who came before. And to rob his memories and replace them made-in-Harvard nonsense.

“Every man should endeavor to understand the meaning of subjugation before it is too late,” General Patrick Cleburne wrote in 1864. “We can give but a faint idea when we say it means the loss of all we now hold most sacred — slaves and all other personal property, lands, homesteads, liberty, justice, safety, pride, manhood. It means that the history of this heroic struggle will be written by the enemy; that our youth will be trained by Northern school teachers; will learn from Northern school books their version of the war; will be impressed by all the influences of history and education to regard our gallant dead as traitors, our maimed veterans as fit objects for derision. It means the crushing of Southern manhood, the hatred of our former slaves, who will, on a spy system, be our secret police.”

Cleburne sought to enlist slaves in the Confederate ranks, for which they would obtain release from bondage. General Lee was to endorse the idea in early 1865. And given the wretched treatment of the freedmen after the war – which gives lie to the Northern claim that they fought for “freedom” and the canting hypocrisy of Lincoln’s second inaugural – it would have been better, maybe, if they had.

And this is why we remember, why we “won’t get over it.” Because we are a people and because this is what made us. We became the Southern people. Not a regional subset of the American people, whatever that may be these days. Not some hyphenation. But the Southern people, born in camp, campaign and the carnage of combat. And so, maybe, we may march to Valhalla or the gates of Heaven: the army of the Southern people commanded by General Lee, the greatest among us, and summoned by fate or providence to become the icon of the nation.

These are, indeed, dark times. Lincoln refounded the Union in blood and plunder and now his heirs, the ostensible elites, are fat and stupid from gobbling down the seed corn. Its war against the Southern people has now expanded to include our Northern friends – the descendants of the Billy Yanks who even now are flocking to Tennessee or Texas to escape the ruin of Lincoln’s nation.

Sometimes it seems General Cleburne’s counsel is most applicable: If we are to die, let us die like men.

But on General Lee’s birthday, to him the last word:

The truth is this: The march of Providence is so slow, and our desires so impatient; the work of progress is so immense and our means of aiding it so feeble; the life of humanity is so long, that of the individual so brief, that we often see only the ebb of the advancing wave and are thus discouraged. It is history that teaches us to hope.”

Hope here is not the “hopium” of politicians: vote harder and you’ll get more free stuff and the right to inflict harm on your enemies without fear of consequence and maybe a gig at a think tank composing spicy tweets. General Lee meant instead the long march of history, and the patterns of rise and fall, fortune and misfortune, in the lives of nations and of men. The Union is not “eternal,” for which we should all give thanks. One day it will lose all power to afflict us, and the rest of the world. Some new power or set of powers will arise; it, too, will grow fat with greed and corruption, and it too shall fall.

But governments have little or nothing to do with the souls of men, and all of them shall one day perish from the earth. All flesh is grass, the old books say, and all things built with human hands will one day be lost. Happiness is fleeting, and every good and beautiful thing must be paid in blood.

But there are moments of beauty and transcendence, when circumstances force men to reveal themselves, reveal the stuff of which their souls are made. In the great tragedy of 1861-1865, General Lee and his soldiers showed themselves possessed of ferocious courage, a nobility of spirit, a defiance and resolve and an endurance never before seen in the Americas, and that will never be seen again.

We are the sons and daughters, the bravest and most noble to ever draw breath on this continent, who fought like lions for the land they loved from a wicked invader, and who in defeat and despite their humiliation never forgot how bravely they fought, and how bravely they defied the invader. And their commander on those bloody fields, the father and the soul of the Southern people: General Robert E. Lee.

May his memory, and that of the Confederate soldier, be eternal.

The views expressed at AbbevilleInstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.

Amen!

What passion!…and a very interesting family history. The readers of this article (myself) need to attend a conference given by Enoch Cade.

Excellent speech, Mr. Cade. It’s a concise but comprehensive chronology of General Lee’s leadership and generalship of the Army of Northern Virginia, its men, officers, and the Southern people. Free of unnecessary what ifs-, too. (I allow myself “What if President Davis had Lee in command at First Manassas instead of behind a desk in Richmond… and why didn’t he?”) As tragic as was your great-great-grandfather’s death before the end, I’m certain from knowing of others’ sentiments that he had little regret for the course he followed.

Little recognized today – at this very moment there are attempts to diminish General Lee even with Southerners. Among a people who know longer read books, repeat viewings of the movie Gettysburg has become the classroom for history showing Lee as a doddering old fool. The movie is fine for what it shows but it shows very little of what happened over the campaign and three days of battle, including Pickett’s charge. Gods and Generals – a great movie if you fast-forward past the Yankee parts – further shows Lee as little more than an observer. I see every day online, “Lee should have listened to- ” and “Jackson would have told Lee to- ” from Southerners. Because of woke, Lee will never have a movie. I doubt my emails to ICON, Mel Gibson’s company will have any effect.

One small correction: General Lee was not “beaten’ in West Virginia in 1861. Lee had no command authority over three separate armies, two with political generals, one with a jealous one, during the campaign. Lee was given verbal instructions by Davis. A Lee aide described it: “It was hoped by Davis that the presence of General Lee would tend to harmonize” the three commands. Neither Lee nor any of the three army commanders received formal command instruction. Even Douglas S. freeman missed that one.

White Southern Males freed the world of monarchs. We refused to surrender to the King with the yankees. We killed so many of the King’s men at Kings Mountain, Cowpens and Yorktown, the King had to sue the 13 free, independent, sovereign States for peace. General Lee’s people fought in that war, too. But you are correct, the South lost and in losing allowed the monarchy to reform itself into something George Washington would have fought to the death. Even DJT, the consummate yankee, has had enough of the oppressive fedgov the northern victory thrust upon the “nation”.

Thank you for your efforts to spread truth.