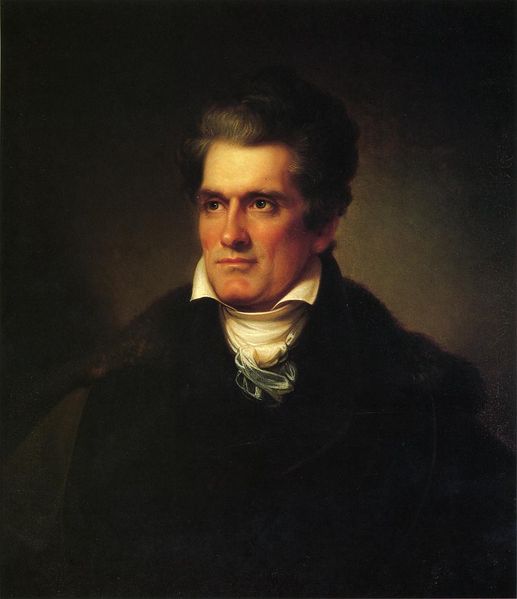

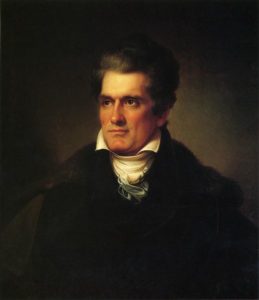

Though John C. Calhoun was a distinguished American statesman and thinker, he is little appreciated in his own country.

Calhoun rose to prominence on the eve of the War of 1812 as a “war hawk” in the House of Representatives and was the Hercules who labored untiringly in the war effort. While still a congressman, he was the chief architect of the banking and tariff legislation of 1816. No less an authority than the banking historian Bray Hammond praised his “perspicacity” regarding the intricacies of banking and public finance. Calhoun also served with distinction as secretary of war, vice president of the United States, secretary of state, and a senator representing South Carolina. He was several times a candidate for president and enjoyed a national following.

Calhoun, together with Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, made up the “Great Triumvirate,” the leading political men of the antebellum period who shaped its policies and framed the issues of its great debates. Calhoun surpassed Clay and Webster as the statesman who most clearly perceived the dangers threatening the Union. Despite his achievements, however, few American politicians have been so vilified as Calhoun, especially in recent decades, yet he was one of our greatest champions of liberty, of the compact power of the states against federal consolidation. Though he is most often associated with the rise of secessionism, he was in fact a devoted servant of the Union, while nonetheless ever vigilant, both as a statesman and a political philosopher, against its potential for tyranny.

Calhoun was never without his critics. He is customarily charged with inordinate political ambition and hypersensitivity about his reputation. For some, Calhoun is a symbol of white supremacy and racial bigotry. Yale University, Calhoun’s alma mater, recently removed his name from Calhoun College, yet he is still recognized as one of Yale’s “Eight Worthies.” More subtle critics suggest that his sectional loyalties blinded him to any vision of national greatness. A recent and not unsympathetic biographer, Robert Elder, has written a book dubbing Calhoun an “American Heretic,” which is a curious appellation for a man whose ideas and political principles are grounded solidly in the American political tradition. And of course there is the legend of Calhoun the “cast-iron man,” the cold and aloof metaphysician who reputedly composed his love letters with the word “Whereas….” All of this is gross distortion and caricature.

Calhoun was a man of his time. He was no more ambitious or touchy than Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, James K. Polk or a host of other politicians in the antebellum era. As for his views on race, Calhoun’s belief that the United States was a white man’s country, and that Europeans were superior to Africans, was standard fare in antebellum America, North and South, no matter how offensive we may find such beliefs today. Political opponents called Calhoun’s devotion to the Union into question from time to time, but no serious scholar of Calhoun believes these charges were accurate.