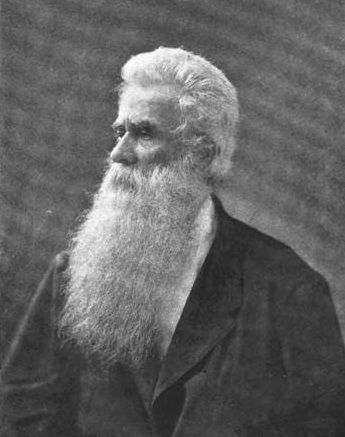

William S. Plumer, born in 1802 in Pennsylvania, was a renowned Presbyterian pastor and theologian. Though he was raised and spent many years in the North, he held the pulpit of several Southern churches before the war between the states broke out. It was during his time in the South that many people, including some within his own church, accused him of becoming a Confederate sympathizer. Plumer, known throughout the Christian community, became a household name between 1861 and 1862 with his refusal to support the Union forces in military engagements.

Returning to Allegheny County, PA, in 1854, Plumer served as a local Presbyterian pastor and professor at the Western Theological Seminary, which later merged with another institute to form the modern-day Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. Before he was appointed a faculty member, Plumer served churches in Maryland and Virginia. His time as pastor at the First Presbyterian Church of Richmond, VA (1834–1846) was when his critics argued his Confederate sympathies ultimately propagated. Such accusations were preposterous, according to Plumer. His views on the war were quite simple; he felt that the church was no place to support military engagements of one’s own kindred. Further, he remained adamant; Scripture supported his viewpoint that clergy should not mix political matters with the teaching of the Bible.

His critics maintained his refusal to label the war as a “rebellion” yet refer to it as a “revolution” only proved his loyalty was not with the Union. Plumer did not pray for specific outcomes of battles nor God’s interference in providing victories in military engagements.

He did, however, pray outside the pulpit for “national peace, for elected officials, and protection for souls on both sides.”[i] Yet he cautioned against sharing any specific prayer regarding a politician from the church. He argued individuals should cover such matters in prayer privately.

Historian Sean A. Scott comments on Plumer’s position:

An Old School Presbyterian, he held conservative principles theologically, politically, and socially, and these views conspicuously set him apart from many Northern clergy who were openly patriotic, Republican, and increasingly antislavery in their public pronouncements. Unfortunately for him, during the Civil War many Northerners demanded more overt displays of patriotism than his conscience would allow him to make.[ii]

While his seminary initially appeared to accept his political positions, his church did not. Church members met privately and demanded that Plumer take a “stance from the pulpit, specifically, on the Sabbath regarding the rebellion of the South.”[iii] He responded with a “nine-page defense of his position where he emphasized he prayed for elected officials (privately), paid taxes, obeyed all laws, and even refrained from voting since moving to the Pittsburgh area.”[iv] Adhering to the sovereignty of God to include the Lord’s judgment on sin, Plumer maintained that God’s will would occur on Earth in one way or another. This included the outcome of the war. On the national fast day in New York City, he shared the following:

A few days since I came to this city by steamboat, and in passing Staten Island I looked out and saw the spot upon which, 83 years ago my father stood breast to breast with the bold Britain and shed his blood to gain the Nation’s freedom. As I gazed forth, I thought of the dangers which now threatened our prosperity, and I prayed to God that I might not live to see the dissolution of that Union, in the formation of which my father’s blood was spilled. I have a strong hope of the mercy of God, but we have sinned deeply. We have blasphemed His holy name, we have insulted him, and broken every commandment which He gave to us, till I dare not say that Sodom and Gomorrah were worse than America.”[v]

Plumer refused to accept the notion that the North was more righteous than the South. Such a position became further tested when President Lincoln declared a proclamation on “April 10, 1862, that asked for prayers and support from God Almighty, and more precisely, asking clergymen to pray for the nation during public worship.”[vi] Not surprisingly, Plumer refused to give in to such demands and maintained that the pulpit must be apolitical. This appeared to be the tipping point for most within his congregation. Members held private meetings and demanded action from their pastor. Once again, Plumer responded with a twenty-two-page defense quoting the scriptures to support his position. Ultimately he replied, “Patriotism is a good thing, but patriotism will save neither you nor me.”[vii] A split within the church ensued, eventually leading to a Presbytery meeting and vote. Plumer won and several church members left the Allegheny congregation.

Plumer’s refusal to give in to his congregation’s wishes made national news. The Buffalo Commercial (NY) newspaper shared the following: “Dr. Plumer, a professor in the Theological Seminary, is also pastor of the Church. He is a Secession sympathizer; refused positively to pray for the Government; said he would not ask the Lord to on one side or the other in the war.”[viii] Similarly, in a lengthier column, the Bedford Gazette wrote:

The Doctor (Plumer) was requested by some of the members of his congregation to pray for the success of our armies in the field, but he refused, alleging that the whole question of the war, its causes and results, was a political matter with which ministers of God had nothing to do, and that he did not feel justified in alluding to the subject at all in his petitions. He was further firm in the belief that no number of battles or victories could bring about an honorable peace, and he could not, consequently, ask God to give our arms success or unite in thanksgiving for the same.[ix]

As time progressed, additional efforts attempted to remove Plumer from the pulpit and church members continued to leave. Publications across the North cited that women within the congregation had saved the fate of their pastor. Again, the denomination’s “Presbytery took the issue up in a formal hearing,” where he prevailed with the blessing of his denomination supporting his apolitical stance. In the extreme, one opposition party wrote to the Philadelphia Press angrily declaring, “Does not equal justice require that he too should be silenced? Shall he be permitted, even in this indirect way, to give aid and comfort to the enemy? Is a traitor in Allegheny town entitled to greater lenity than a traitor in Alexandria?”[x]

The written attacks continued and by September 1862 it was clear the Presbytery was slowly changing its mind in openly supporting Plumer. Presbyterian publications The Pittsburgh Banner and the Cincinnati Presbyter condemned the pastor. Churches within Ohio questioned the loyalty of Plumer. In the extreme, he gained the label of Judas Iscariot. Almost all major Christian and metropolitan publications across the North covered the story of Plumer. Politicians, even some from outside of Pennsylvania, referred to the pastor as a traitor. Likewise, other regional preachers denounced him and remarked he “was nothing but a Confederate sympathizer.” Plumer never ceased to fight as he defended himself vocally and in official writings. He regularly responded to various news publications in written declarations of justification for his stance on remaining neutral from the pulpit. While there are differing accounts of the final events surrounding his resignation, his opposition finally got their wish as he resigned as both a pastor and professor at the seminary. His resignation from the seminary declared:

Fathers and Brethren- I hereby resign my Professorship in this Institution.

I take this step not because I do not love my work here. On the contrary, it is truly pleasant to me. But my peace is destroyed, my life is embittered, and my health is suffering from cruel calumnies, which I have borne as silently and as patiently as I could, and from the line of conduct pursued toward me by some of the Directors, approved, as I fear, by others of your number.[xi]

By the fall of 1862, no longer welcomed in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Plumer fled to various Northern states to fill in as pulpit supply. His journey found him in Connecticut, New York, and even returning to Pennsylvania, though this time to Philadelphia. However, his reputation as disloyal to the Union effort followed him in various positions.

After the war, Plumer made his way south. He returned to his passion for teaching and again held the position of professor from 1867 to 1880 at Columbia Theological Seminary in South Carolina. It was apparent that most Northerners and individuals within his denomination labeled him as a treacherous preacher and sought to remove themselves from his company. Thankfully, he found a home in the South.

Plumer’s work continues to be studied. The late theologian authored more than twenty-five books, including several commentaries. Today, his legacy remains impressive. The reader can find his work through publishing companies such as Banner of Truth and Reformation Heritage Publications. In addition to his books, he composed several essays on theology, biblical tracts and even authored numerous “anonymous writings.” Unfortunately, such accomplishments did not save his reputation in the North. Thankfully he stood firm in his faith and doctrinal beliefs. In his later years, he became moderator of the Southern Presbyterian Church while residing in South Carolina.

Plumer was no heretic, nor was he disloyal to his country. He was a passionate theologian who remained consistent in his beliefs and teachings. His work is strongly recommended and applicable today for any reader interested in theology. Worthy of high praise are the following books: Theology for the People-or-Biblical Doctrine Plainly Stated, The Christian, his commentaries on the Psalms, Hebrews, and Romans, and lastly, for children, Plain and Simple Thoughts for Children and Parents.

*************

[i] Sean A. Scott, Contested Loyalty: Patriotism Will Save Neither You Nor Me (New York: Fordham University Press, 2018), 171.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Rev. William S. Plumer, “National Fast Day Prayer,” Pittsburgh Gazette, January 8, 1861.

[vi] Scott, Contested Loyalty: Patriotism Will Save Neither You Nor Me, 172.

[vii] Ibid., 173.

[viii] Editor, “A Breeze in Church,” The Buffalo Commercial, June 16, 1862.

[ix] Editor, “Allegheny Central Presbyterian Church,” Bedford Gazette, June 27, 1862.

[x] Timothy L. Wesley, The Politics of Faith During the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Press, 2013), 59.

[xi] Editor, “Resignation of Rev. Dr. Plumer,” Vermont Chronicle, September 20, 1862.

Reverend Plumer believed in malice toward none and charity for all. Prematurely.

He done good!

And that was back before ol’ LBJ gagged the pulpit. That if the gov was preached about, they’d lose their 501C3 and their offering plate would be taxed.

I do pray God’s will be done on earth as it is in heaven. However, I don’t believe God’s will has a thing to do with who has the biggest or most guns.