A review of With Malice Toward Some: Treason and Loyalty in the Civil War Era by William A. Blair (University of North Carolina Press, 2014) and Secession on Trial: The Treason Prosecution of Jefferson Davis by Cynthia Nicoletti (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Was the act of secession in 1860-61 treason? This is one of the more important and lasting questions of the War. If so, then the lenient treatment of Confederate officers, political figures, and even the soldiers themselves following the War was a great gesture of magnanimity by a conquering foe never seen in the annals of Western Civilization. If not, then the entire War was an illegal and unconstitutional invasion of a foreign government with the express objective of maintaining a political community by force, an act that represented the antithesis of the American belief in self-government regardless of Abraham Lincoln’s professed admiration for government “of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

Until recently, the modern academy has not given the topic much scholarly attention. Post war discussions of secession and treason were best addressed in what is now classified as “Lost Cause Mythology.” Historians regularly cast aside works by Albert Taylor Bledsoe, Jefferson Davis, and Alexander H. Stephens as examples of special pleading written by sore losers determined on refocusing the narrative away from slavery. Most mainstream historical literature considered it a foregone conclusion that the War was a “righteous cause” to forge a new union, as many of the Radical Republicans professed during Reconstruction. The South had been defeated, its leaders were on the “wrong side of history,” and secession, while not necessarily classified as “treason,” was forever buried as an illegal and inexpedient over-reaction to a Lincolnian bogeyman.

But as historians William Blair and Cynthia Nicoletti illustrate, during the War and its immediate aftermath, these questions were far from settled. And in 2018, with the charge of treason being leveled against anything Confederate in popular culture, finding a historical understanding of the subject has become a pressing need.

Did Northerners consider Confederate citizens to be traitors? Blair argues that during the War the answer was a resounding yes, though his confidence waivers when discussing the sentiment of Northern Democrats, many of whom regarded the War as an unconstitutional invasion of a separate government and the bastardization of American principles. Blair documents both the strategy and tactics by the Lincoln administration and the Northern public at large to combat “treason” in the North and occupied South. He concludes that Lincoln violated the Constitution, though he considers the offenses minor and necessary to preserve order, argues that the United States military went too far on several occasions regarding treatment of Southern civilians, and does not understand why troops were deployed to Northern polling places during the War. The abuse of civil liberties was palpable.

But by 1868, Blair suggests that the “traitor coin” turned up heads. Northerners discarded their acrimony for reconciliation, though in the early twentieth century some began dusting off what can properly be labeled the “righteous cause myth,” my words not Blair’s. Union veterans and their descendants bristled at the universal acceptance of Confederate leaders and soldiers as “American” heroes. Were they not sill traitors? Most of the American public didn’t seem to think so, and with good reason. They weren’t, at least regarding a legal understanding of treason. It seemed Bledsoe, Davis, and Stephens had won the legal argument and perhaps even the “hearts and minds” of the American public. Even Republicans Teddy Roosevelt, William H. Taft, Warren Harding, and Calvin Coolidge buried the Party’s longstanding tradition of anti-Confederate sentiment and embraced the former Confederacy as part of the American tradition.

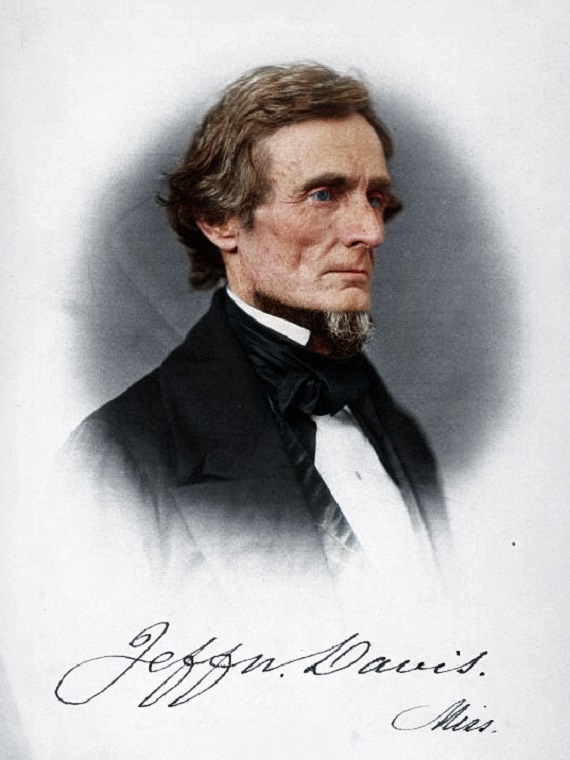

Nicoletti’s treatment of the potential Jefferson Davis treason trial underscores Blair’s position on postbellum Northern sentiment. Nicoletti has written the first comprehensive study on Davis’s incarceration, the details of his impending trial including fine profiles of the legal teams both for the defense and the prosecution, and Northern public reaction to the issue. Some of her arguments buttress long held assumptions concerning why the trial was never held—most importantly the prosecution was unsure if they could secure a conviction—while others favor the modern establishment agreement on secession and the War that followed, i.e. it was all about slavery and “white supremacy,” and that the Supreme Court finally “settled” the issue in the 1869 decision of Texas v. White. It didn’t. This is unfortunate because she missed an outstanding opportunity to reshape both the public perception of secession and the historical “consensus” on postbellum American thought.

Nicoletti, in fact, explains why she feared writing this book and why she went out of her way to “show” she despised the South and the “Lost Cause:” she wants a job and tenure. That speaks volumes about the historical profession. Historical inquiry, even on sensitive and “controversial” topics should produce accolades, not resentment or punishment, but the gatekeepers of acceptable opinion do not reward independent thinkers who tackle topics that may point to conclusions they wish to avoid. The Davis case showcased some of the best elements of Northern society, and Northern reaction to his release and the resulting silence on the treason question is one of the more fascinating episodes of American history. How could a section that just waged four years of bloody war against another people cheer when the leader of that effort was released from prison? And how could men who denounced the Confederacy pool money to free one of its most conspicuous symbols? Simple. The majority of the Northern people considered Davis to be an American, the Confederacy to be American, and the Confederate cause to be worthy of respect. The same cannot be said for modern American society, which is why studying Northern opposition to “Mr. Lincoln’s War” and the postbellum response to secession are more interesting in many ways than the War itself, both North and South.

Blair argues that for most Northerners “treason” was always a political rather than legal question, a pejorative used to rally support for the men in blue and demonize those in butternut. The fact that Davis never faced trail in open court is a validation of that position, for once the issue moved from the realm of political to legal, it became unclear if Americans, both North and South, could hang a man for a “crime” that the founding generation committed in 1776. That would be un-American and nearly everyone in America in 1867 could understand that, even if a few “righteous cause” mythologists grumbled about the result and modern Monday morning quarterbacks assert that they would have hung every Southern “traitor” from the highest tree and fearfully punished the Southern people.

What these armchair generals don’t realize is that the South was fearfully punished, and by blustering about retribution, they expose how truly un-American the United States has become. But one should expect no better with a modern education establishment that embraces “righteous cause mythology.” Magnanimity and reconciliation are now deemed to be detrimental to the American experience while victimization, reprisal, and “justice” dominate public opinion. If the trial were held in 2018, Davis would not make it to the courtroom.

If you enjoyed this piece, you will also enjoy Dr. McClanahan’s 25 lecture course on “The War for Southern Independence.”