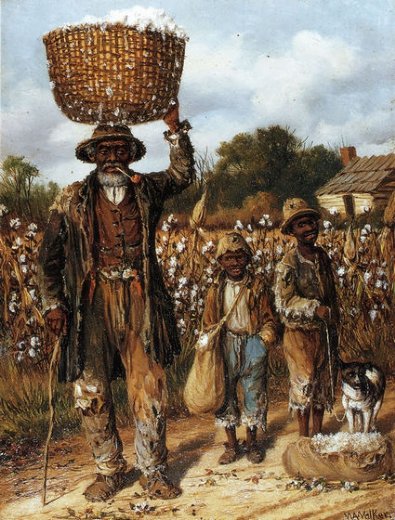

He was old and black…negro…colored he’d say and he had been for a good while. “I know you.” He said. “You watch me thru de windah.” I nodded as our first conversation concluded.

He drove his old mule down the newly-paved asphalt roads, begrudgingly regal on an old scrap tire his plow rested…the point hidden inside the body of the tire like a smuggled dagger…the plow proper riding like a lazy sultan on a black magic carpet as the ancient negro caressed callous-worn bent limbs that hung over open road like wooden Jesus on the cross.

Garden plots had once been the rage and his daily bread. Before Piggly Wiggly and Winn Dixie had come. His fields to till had shrunk with the surrender of the Axis powers. His empire had briefly swelled during the war in Korea but Vietnam had not born fruit as of yet…and it would not. Vietnamese gardens went to seed. Still he made his living and his rounds thru the neighborhoods. Old women paying him to turn their gardens in the old ways so a lucky kid could watch earth roll like a fat black baby reaching for his only toy.

I never saw him plow. Only heard stories. “Ole Jim, his furrows are the straightest you’ll ever see.” My dad studied his work. “Nobody puts in a garden like that these days…no one has enough land here in town.” It was true, I suppose. By the time his mule got started, it was time to turn around and even I knew enough to say mules don’t like to plow in a circle. “Get them going in a straight line by setting some stakes first to put in the first row…with a string if you have to…then stay same distance from it on your next runs. Have a pocketful of corn and give him a nibble at the end of a couple of rows. He’ll pull straight as a hawk on the fly.” My granddaddy used to say.

When Jim ran out of gardens, he could have sold his mule and put himself out to pasture but he didn’t. He went to work taking care of the last stable in our neighborhood. In the quarters, next to the colored cemetery. Old rundown horses and mules no one cared enough to kill. They kept the grass eat down around the headstones and conch shells…the occasional disrespectful dung pile was merely a cost of doing business.

His other job in the warmer months, if you could call it a job, was to watch the swimming hole. In the old days, as the story went, the black kids could swim as well as the whites but after LBJ, the black daddies went their own way and no mama or auntie could teach or wanted to teach a half-drowned clawing child to swim. So by default, the black kids watched the white kids swim and called us crazy because we went into water over our heads.

Old Jim watched. Smoked. Rolled another. Said nothing unless he was asked unless it was a warning not to drown and always by one of us…never one of them. He would nod his head. Smile softly. Say “Yes, Lawd” and “No, chile” with equal enthusiasm. Watching the black kids refuse to swim he would become melancholy.

While he watched us, he worked with his leather saddle bags…his “grip” he would call it and he would make magic and rope.

At times, I would just sit and watch those hands…whipping and twisting like an oyster shucker winning a money bet and at times caressing and combing his work and I would wonder who had taught him…and the one before…and the one before.

He’d look at me. Out of his grip would come a handful of hair. Mane and tail. I do not know how he got it. I know it was considered cruel to cut a horse’s tail too short but the mane, I suppose was fair game.

He would card it…run it thru blocks with a bed of tiny nails to straighten it out and give me a hank. “Hole dis, chile”, and he would have me holding a coke bottle’s thickness of hair…like a limp kitten…and then he would start to spin a strand with a whirling contraption that looked like a one-armed propeller and he would tell me to back away and to feed it myself and the first time I was nervous but got the hang of it until the hair ran out. Then he would grab other strands into three or more piles and start to weave, braid and plait. He would twist and turn and say, “No, chile” or “Yes, Lawd” and pick from already prepared piles of yellow and black and white and red and he would call the horse by name and its real color…not those of the spectrum…but those of a man who had to know which was the roan and which was the dun.

The new rope would be spliced into a piece he was working on in another pocket of his grip and the rope was black and gold and red and white and a checkerboard pattern if you took it and spun it slowly in your hands and he would smile because you noticed.

“Why do you sit and watch us?”

“Is my jawb, chile.”

And he would say no more.

One of the older boys called to me…one of the swimmers…”hey, last name- you can swim, can’t you?”

Of course I could swim; he was baiting me.

“Better’n you! Better’n anybody here!”

“Nobody likes a bragger.” Under his breath.

“Yessr”…the sir part said real low…just between the two of us.

“You know what good times is?” I didn’t think I knew the answer, so I didn’t say.

“…when nobody can hear your belly and you can sleep all night without having to stand watch…thems is good times…when you got a hoss dat call to you at dark tellin’ you good night…and a woman you don’t have to talk to…she just know”…he paused…”dat’s good times…when yo babies be piled up on you like sacks of taters and you laughing and crying and praying so hard you wakes ’em up and dey looks at you and goes back asleep. Dat’s good times.”

“Go on, now.” And he would sit with the rope between his palms…wide and white on one side…wide and black on the other except for the scars and fingernails…tightening the weave he would say…getting it to set. And he would wet it and watch it dry until it was just right and then spin it and tighten it and it would have the consistency of liquid glass. At times he would pull on it with his teeth or put it under his feet and try to pull it apart but I think he was just messing with me then…and the piece would go back into the grip because the sun was getting down into the trees.

He would walk back up toward the cemetery…head low, whistling or singing to himself…brogan shoes scuffing clay or asphalt. People would honk or wave as they went by or they would pass him in a cloud of dust…he waved either way.

And once in a while, men would stop and money would go one way and a worthless lasso or halter would go another…the uncounted money disappearing into an empty pocket…and later that night would vanish into a horseless barn a work of art.

Thank you for this story. It takes me back to my youth, and my “Uncle” Jim the sharecropper and his gigantic redbone mule and the furrows ‘we’ plowed. Thank the good Lord for smart mules, and tolerant relatives. And thank you for sharing your favorite expression. It’s a good one.

Thank you, sir.

Takes me back to my childhood. Life was so much simpler then. A white boy could call a black boy friend and mean it. Hatred seemed like it was a world away from us. Wish it had stayed like that always.

As my dad would say, “you and me, both”.

Thank you, sir.

Loved this story. Brought up nearly list memories of Saturdays when my younger brother and I were preschool through 2nd grade “working” in Granddad’s pecan groves.

Our “Jim” ( as so many of the few old weathered black men I knew) was Jim also.

Some how he always showed up about the time we arrived from Birmingham. He could outwork our Dad ( which we had thought impossible until we met Jim!) and of course us. When we went for lunch Jim always had a pack of crackers and a RC Cola. He was consistently offered more but always refused. We came back from lunch to find him working away. Dad would let us stop just when the sun dropped out of sight, putting our tools up and loading the car. Jim, when asked, would reply that he was “ a war baby” but never told us kids which war. Dad remembered him as middle aged when he was a child. Our last sight as the we drove away was Jim, heading the opposite direction, waving, humming to himself, and walking as briskly as he had worked all day!

Thanks for the memories, “Jim”!

Thank you, sir.

You can learn much about life watching a 70 year-old man dig a splinter out of his palm with a folding knife and then wipe the blood on his pants leg and get back to work. Black or white. I was blessed to know many such men.

Ole times should never be forgotten. What a great story.

My father was born on a cattle farm near Inverness, Alabama in 1948. A black family lived on the farm with them and their son was my Dad’s only friend. Grandma forced Grampa to leave the farm around 1960 because Dad and his friend we’re digging worms where they were told not to and the boy got bit by a cottonmouth. He survived. Grandpa got a job selling fertilizer and they moved to town, Columbia, South Carolina.

I was born in 1980, and from my perspective, we seemed more truly integrated during segregation, than during integration.

Anyways, thanks for your article, I enjoyed it.

Old times there are not forgotten…look away…Dixie land.

Thank you for your story, sir. I am sure Grandma had at least one more reason for pushing Grampa, but who says a moccasin bite can’t be icing on a cake? It’s not a good story without at least one scar.

I think we were more naturally curious of the lives we weren’t supposed to be “sharing”. You must remember, there were never more black businesses in existence than in the days of segregation. The man in my story was independent, business-oriented and crossed racial lines with ease. He was an example to everyone how barriers don’t exist when supply is limited. The reason I never saw him plough is because we didn’t have much money in our neighborhood. Jim was heading to work on the other side of the bridge.

My little brother read this story a few years ago. He asked if Jim was real. My baby brother is only 16 years younger than I am…that’s how quickly things change.

God bless you and all the other commenters…even on a site such as this one, you take a risk reliving your memories when a large portion of the public never experienced the world as you did. I know the lies are easy to disprove…I have spoken to dozens if not hundreds of black people about the fact no one was ever enslaved in the New World. It was black Africans enslaving other black Africans…long before the first European ship set sail. Any who ever gave even a passing ponderance realized this fact intuitively. The lies are so deep and so interwoven, the entire sham falls apart by picking one little seam. It wasn’t Southerners who guarded the sea lanes so the slave ships could pass with cargo intact…nope, that was the British navy. It wasn’t Southerners who passed the Corwin Amendment…nope…there wasn’t a single Confederate State present at that session of the United States Congress. BTW, the Corwin Amendment protected slavery EVERYWHERE…including the slave States still remaining in the United States. Think about that the next time someone tells you the war was over slavery. The expansion of slavery into the territories as a cause of the War is very different from the War being over slavery.

All we have to do is stand up and speak the truth. We may wish things had unfolded differently after the War…race relations were destroyed when the 14th Amendment was forced upon the South at gunpoint. Former Confederates were disenfranchised, and the true civil war began.

All wars are fought over money. Slaveholders, black and white and brown in the South lost 4 billion dollars on top of the cost of the war, which was in the billions…the GDP of the entire united States in 1860 was…4…Billion…dollars. In the presence of such extreme poverty, it’s a wonder the South ever recovered. You can thank conditioned air for that recovery as well as the subsequent yankee invasion.

Amen!