We are threatened by a powerful, dangerous, conspiracy of evil men. The conspiracy is the enemy of free institutions and civil liberties, of democracy and free speech; it is the enemy of religion. It is cruel and oppressive to its subjects. Its economic system is unfree and inefficient, condemning its people to poverty and deprivation. It has a relentless determination to spread its system to other peoples and other lands. Its threat comes not only from without, but from its collaborators in our midst.

Its aim is total domination. To compromise with it is impossible, because its leaders are treacherous and only agree to compromise in order to prepare the way for further aggression. For them agreements are made to be violated. Living with this evil permanently is thus impossible; there can be no peace or security until it is completely eliminated and its place taken by a system like our own, for our system is the best hope of all mankind. Our way alone guarantees freedom, peace, and prosperity.

This is an accurate representation of how the Republican Party propaganda of the 1850s depicted the South, which was controlled, said Republicans, by what they called the Slave Power. The Republicans’ central platform plank was the necessity of resisting the aggressions of this dark conspiracy. The Slave Power was used to justify the creation of the Republican Party in 1854. It was the symbol that was made to stand for all the accumulated hostility, all the differences— economic, social, political, religious, ideological—that had come to divide North and South.

According to the Republicans, just what was the Slave Power’s master plan, and how did it intend to carry it out?

First of all, with the help of its Northern fellow-travelers, it had seized control of the Democratic Party and, through that party, the Federal government. It had already fomented the Texas Revolution, annexed Texas, provoked the war with Mexico, and acquired California and the Southwest. Next. Republicans told the voters, the Slave Power Conspiracy would carry slavery throughout the Western territories, from the Canadian to the Mexican border, and from there into the free states themselves. Then it would overthrow the remains of the Constitution and set up an oligarchy of slaveowners to rule the nation and spread slavery into the Caribbean and Latin America, the ultimate aim being a gigantic empire based on the conspirators’ un-American ideas and institutions.

This remarkable vision was not the delusion of unbalanced extremists. Fear of the Slave Power Conspiracy was an important part of a political creed that attracted the nearly 2,000,000 Northerners who elected Abraham Lincoln in 1860. It was a fear assiduously cultivated by party leaders. Lincoln’s famous House Divided speech of 1858 is a good example. There he affirmed his belief in the Conspiracy and warned that if the Republican Party was not victorious the United States would become all slave, North as well as South, whereas if the chief weapon of the Conspiracy, the Democratic Party, was repudiated. Republican policies would result in the total elimination of the threat.

What were the facts, facts as readily available then as now? What progress had this awesome menace made toward its goals by the time Lincoln was elected?

The record was clear. Five Northern or Western states, but no Southern state, had been admitted to the Union since 1845. The territory of Kansas, touted as the battleground between freedom and slavery in the 1850s, had overwhelmingly rejected a proslavery constitution in 1858. Slavery had been legal in the Southwest since 1850 and in the Louisiana Purchase since 1854, yet how many slaves had the Slave Power Conspiracy actually thrust into this vast area? In Kansas, where, according to the Republicans, the Slave Power Conspiracy had put forth all its strength for several years, the 1860 census showed two slaves in a population of 107,000. In all the territories, including Kansas, perhaps 1,000,000 square miles, there were 46 slaves and 20 slaveowners. The census also showed that slaveowners made up 1.2% of the total United States population and that the South’s share of the entire population in comparison to the North’s was continuing its long decline. The South had never had a majority in either house of Congress. Its share of seats in the House of Representatives had dropped along with its share of the population. It had lost its equality in the Senate in 1850. With all these commonplace facts before them, how would people believe in the danger of a great Slave Power Conspiracy spreading over the nation?

Some historians have written about what they call the “paranoid” style in American politics. They find in our past a deeply rooted willingness to believe in gigantic conspiracies. No one would deny that there are such things as conspiracies. The difference is that the paranoid style uses conspiracies as an all-encompassing explanation for whatever seems threatening. For instance, Lincoln was killed as the result of the Booth conspiracy, but Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton believed that Booth was a tool of the Slave Power and immediately proclaimed that Jefferson Davis, the leader of the Slave Power Conspiracy, was responsible for Lincoln’s assassination and issued a reward for his arrest.

The paranoid style goes far back. Many Revolutionary War leaders believed in what they called “a PLAN…systematically laid, and pursued by the British ministry, for enslaving America.” And the Declaration of Independence itself referred to a “design to reduce [the colonies] under absolute despotism.” New England Federalists saw Thomas Jefferson as the agent of the Red Revolution that had taken over France, a Jacobin whose election would be followed by a Reign of Terror. “Murder, rape, adultery, and incest will be openly taught and practiced,… the soil will be soaked with blood…” Northern Federalists also claimed that Jefferson and his followers were part of “a worldwide conspiracy against Christianity, masterminded by a secret order, the Illuminati,” which had been spread throughout Europe by the French Revolution and thrust into the United States via subversive societies.

In the 1820s a hysterical fear that the Masonic order was going to destroy American democracy led to the formation of the Anti-Masonic party in New England, New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio-the seedbed of abolition. At the same time other Americans sounded the alarm against the “Monster Bank,” the tool of eastern and British capitalists that was being used to make the rich richer and, if not stopped, would eventually take over the country. Beginning about the same time and reaching a climax in the 1850s was the fear (mainly in the Northeast) of that ancient arm of Satan, the oldest conspiracy of all, the Roman Catholic Church, a fear that led to convent burnings and the formation of a large political party in the 1850s. By this time, however, the Slave Power had taken front rank in the parade of conspiracies, although for a time the contest for the villain was a toss-up between the South and Rome. They were seen as natural allies, twin threats to the American way.

To repeat, the fear of the Slave Power Conspiracy was the essential ingredient in the creation of the Republican Party. Had there been no such party, there would have been no war in 1861, for it was fear of the Republicans’ intentions that led to Southern secession.

How did so many Americans arrive at this way of thinking about human affairs? This alertness for conspiracies, this defining of all issues in moral terms, this inflation of little things into monstrous threats? The paranoid style grew stronger as the years passed and became immensely stronger in the wake of the intense revivals that swept the North in the 1820s and 1830s and again in the 1850s. Religion came to permeate political rhetoric, and for Northerners politics took on the aspects of a religious crusade. These developments, to a significant degree, reflected the influence of New England on the Northern mind, for New England was the main source for the idea that Americans were the Chosen People of God.

Chosen for what? Northerners of this persuasion believed they were chosen for nothing less than the redemption of the world and the advancement of the millennium: the kingdom of God on earth that would precede the Last Judgment. Belief in the coming millennium was coextensive with revivalism. The eschatological framework of millennialism was the Revelation of St. John the Divine, which looked toward the great struggle between the forces of God and the devil that would culminate in the battle of Armageddon. This would usher in the rule of God and his saints, followed by the Last Judgment, the new heaven and the new earth. Evangelicals of Lincoln’s generation believed that the United States, established by God far from the corruptions and Antichrists of the Old World, was evidence of the coming of the millennium and was itself to be the Redeemer nation, destined to bring Protestant Christianity and American institutions to benighted humanity. They believed, moreover, that “only the labors of believers’” would bring the millennium, “and if they proved laggard in their task, the millennium would be retarded.”

The first order of business if America was to fulfill its divinely ordained role was self-purification. This led to an unprecedented era of reform movements, of which the antislavery crusade was by far the most influential. The slaveholding South, like the Catholic Church, was seen as a tool of the devil that must be overcome by the “antislavery gospel” —and it actually became a new gospel, the acceptance of which was the necessary mark of those whom God had elected to everlasting life.

After thirty years of reform and revivals, which pictured Southerners as sunk in sin, corruption, and heresy, the Civil War came, ‘“just before,” one historian observed, “the time many commentators had predicted the millennium would begin.” And when the war came, many saw it as the opening gun of Armageddon. The most famous Northern war song, Julia Ward Howe’s “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” contains a string of images straight from the Book of Revelation. The apocalyptic vision was aptly expressed in a Princeton religious journal of 1861:

[The war] is one of the last mighty strides of Providence towards the goal of humanity’s final and high destiny. A few more such strides, a few more terrific struggles and travail pains among the nations; a few’ more such convulsions and revolutions, that shall break to pieces and destroy what remains of the inveterate and time-honored systems and confederations of sin and Satan, and the friends of freedom may then lift up their heads and rejoice, for redemption draweth nigh.

A leading New York religious paper, The Independent, described the mood when Richmond fell to Grant’s army:

Who can ever forget the day? Pentecost fell upon Wall Street, till the bewildered inhabitants suddenly spake in unknown tongues— singing the doxology to the tune of “Old Hundred”! Shall we ever see again such a mad, happy enthusiasm of a great nation drunken with the wine of glad news? The City of Richmond [had fallen], Babylon the Great, Mother of Harlots and Abominations of the Earth…Rejoice over her, thou heavens, and ye holy apostles and prophets: for God hath avenged you on her. And a mighty angel took up a great millstone, and cast it into the sea, saying, Thus with violence shall that great city be thrown down, and shall be found no more at all. [Compare Revelation:17.5,18.20-21.]

The conquered South, the newspaper argued, should be treated as “territory occupied by the Church of Rome or the followers of Mohammed.” Missionaries were to be sent South to build a true church.

But that was only the beginning. Wrote one latter-day prophet, “The enemy to be assailed and vanquished is generally the same. In India and China it finds its embodiment in a pagan priestcraft. In Europe it is the despotism of Rome. In America it is met in the system of African Slavery. Now in turn has this monster of sin come up in remembrance before Heaven and waits its final doom.”

Today the South, tomorrow the world. And with Protestant Christianity would necessarily go our other God-given institutions. As Methodist Bishop Matthew Simpson said, the American flag would eventually fly “over the whole western hemisphere,” and then “we must take the world in our arms, and convert all other nations to our true form of government.”

The political side of the millennialist movement can be seen in the belief that the American republic was both a harbinger of the millennium and a necessary instrument in redeeming the world. The true gospel could flourish only where our form of republican government also flourished. So political conversion was indistinguishable from religious conversion. Intrinsic to that republican system of government was an economic system: free labor, or entrepreneurial capitalism. God wanted his chosen people to prosper, and the millennium was to be a time of unprecedented plenty because of the “free labor” system. This is all very explicit in the literature of the time. Such a view of things blended smoothly with what might be called secular millennialism, a way of looking at the world rooted in the eighteenth-century enlightenment rather than in St. John’s Revelation, and reinforced by the economic developments of the antebellum period. Thomas Jefferson, like many of his generation, saw the United States as a unique empire of liberty, created in the midst of oppressive monarchies. He hoped that the rapid growth of American population would spread throughout the hemisphere, raising up other republics. The new world would be a bastion of free governments, separate from the dark tyrannies of the old. He believed in “the revolutionary nation’s responsibilities to the freedom and peace and happiness of mankind.” It was the reservoir of the natural rights of man.

By the 1850s this vision had become more detailed and more explicit, blending idealism and profit. A good capsule statement is contained in the famous speech of William H. Seward in the debates on the Compromise of 1850. Then senator from New York, Seward would later be Lincoln’s secretary of state. Like others before and after him, Seward announced that through commercial and other means the United States would renovate the governments and societies of Europe, Africa, and Asia, “and a new and more perfect civilization will arise to bless the earth, under the sway of our own cherished and beneficent democratic institutions.”

The world view just summarized ran deep into our past. Is there any evidence that it persisted after the Civil War, that it continued to shape our national destiny? Of course, in the post-bellum years the country and the world changed and so new influences came to bear on how we looked at human affairs. But despite such changes, important elements of the 1850s world view persisted.

The Slave Power at last died, although for years after the war the Republicans insisted it was only sleeping. Great secret organizations like the Irish Catholic Molly Maguires and the dying Slave Power’s Ku Klux Kian rose to trouble their dreams. The strikes and riots of the 1870s evoked frightening visions of communist revolution and anarchist plots. Gradually these faded. The Slave Power was at last not only dead but buried. The Irish Catholics, if not yet assimilated, were at least politically subdued. The Pope no longer seemed so dangerous. The Republican Party controlled the political machinery; the Democrats were becoming a chronic party of the “outs.” Labor agitation had been successfully contained. The Knights of Labor, the most ambitious and ominous union yet seen, had collapsed.

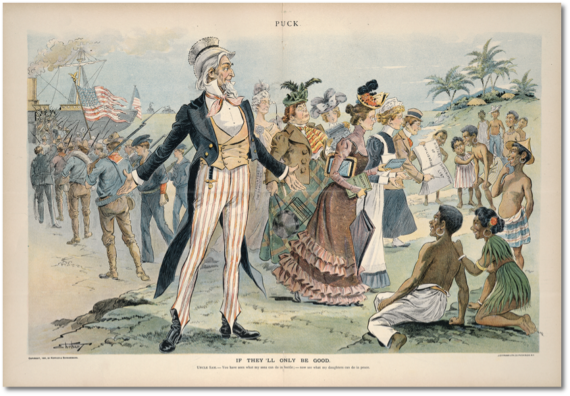

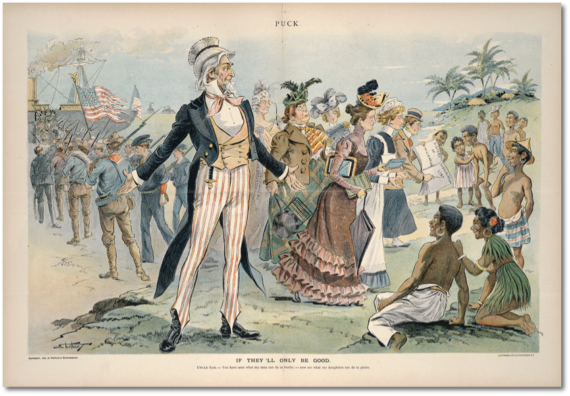

Near the end of the century, however, events abroad revived and activated key beliefs from the 1850s, especially belief in the mission of the United States to the human race. Our sudden war with Spain and our remarkably easy victory struck many Americans as Paul had been struck on the road to Damascus. The scales fell from our eyes. God was pointing the way.

The pivotal event was Dewey’s victory at Manila Bay. Admiral Dewey himself said the hand of God was in it. One religious journal declared: “The magnificent fleets of Spain have gone down as marvelously, I had almost said, as miraculously as the walls of Jericho went down.” One exclaimed that the news read “almost like the stories of the ancient battles of the Lord in the times of Joshua. David and Jehosophat.” Another wrote; “To give to the world the life more abundant for here and hereafter is the duty of the American people by virtue of the call of God…The hand of God in history has ever been plain.” In an attempt to justify the annexation of the Philippines, one journal proclaimed: “We have been morally compelled to become an Asiatic power.” President McKinley reminded American negotiators in Paris,

We cannot be unmindful that without any design or desire on our part the war has brought us new duties and responsibilities which we must meet and discharge as becomes a great nation on whose growth and career from the beginning the Ruler of nations has plainly written the high command and pledge of civilization.

McKinley explained to a group of Methodist ministers how he had reached the momentous decision to take the Philippines:

I walked the floor of the White House night after night until midnight. And I am not ashamed to tell you gentlemen that I went down on my knees and prayed to Almighty God for light and guidance more than one night. And one night late it came to me this way-I don’t know how it was, but it came: (1) that we could not give them [i.e. the Philippines] back to Spain–that would be cowardly and dishonorable; (2) that we could not turn them over to France or Germany-our commercial rivals in the Orient–that would be bad business and discreditable; (3) that we could not leave them to themselves—they were unfit for self-government—and they would soon have anarchy and misrule worse than Spain’s was; (4) that there was nothing for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos and uplift and civilize and Christianize them as our fellowmen for whom Christ also died. [Most Filipinos were already Roman Catholics]. And then I went to bed, and went to sleep, and slept soundly.

Perhaps the classic statement of America’s divine mission was made “ by Senator Albert J. Beveridge of Indiana, fittingly a biographer of Lincoln, upon his return from the Philippines in 1900, He was answering those who said we should let those islands go.

We will not renounce our part in the mission of the race, trustee, under God, of the civilization of the world…Mr. President, self-government and internal development have been the dominant notes of our first century ; administration and the development of other lands will be the dominant notes of our second century…He has made us [our race] the master organizers of the world to establish system where chaos reigns…He has made us adept in government that we may administer government among savage and senile peoples… And of all our race, He has marked the American people as His chosen Nation to finally lead in the regeneration of the world. This is the divine mission of America, and it holds for us all the profit, all the glory, all the happiness possible to man. We are trustees of the world’s progress, guardians of its righteous peace. The judgment of the Master is upon us: “Ye have been faithful over a few things; I will make you ruler over many things.”

The irony of the situation was lost on Beveridge: we had gone to war to rescue the Cubans who were fighting for independence from a nation across the sea. It was a brutal war, yet we presumably were continuing to fulfill our mission, as described by Beveridge and others, by doing the same things in the Philippines as the Spanish had been doing in Cuba.

Our divine mission was paramount in the war with Spain and its aftermath, but as usual it was one side of a coin—the other being the evil conspiracies that we were compelled to overthrow if our mission was to be fulfilled. When we entered World War I, government propaganda told Americans they were fighting a secret conspiracy that had somehow got control of the German people and that had for its master plan the conquest of the whole world. A wave of spy-scares and superpatriotism swept the nation. Then when Germany was defeated, the coin was flipped and our mission came forward, with Woodrow Wilson as the new Messiah. Son of a Presbyterian minister, Wilson had early absorbed the concept of the Chosen People whom he would now lead in a crusade to “make the world safe for democracy,” i.e., to allow all nations to model themselves on the United States. This would ipso facto put an end to war, because our system was moral and righteous, and war was caused only by immoral and evil regimes. During his speaking tour to urge upon the people the necessity for joining the League of Nations, he told one crowd:

I wish [the opponents of the League] could feel the moral obligation that rests upon us not to go back on those boys [American soldiers] but to see the thing through and make good their redemption of the world. For nothing less depends upon this decision, nothing less than the liberation and salvation of the world.

There was, he continued, a “halo” around the gun over the mantle, the gun the soldier had brought home from France. The world had accepted American soldiers as crusaders. It was their infinite privilege to fulfill their destiny and save the world.

The First World War raised up the menace that would take precedence over anything in the past (with the possible exception of the Slave Power) as the greatest conspiracy of all: communism. The communist revolution in Russia in 1917. the spread of political radicalism in the midst of post-war turmoil in Central and Eastern Europe, the formation of the Third International, plus post-war strikes in the United States, led to what historians call the “First Red Scare,” which was seemingly made credible by several acts of terrorism. Widespread public alarm, mob violence, anti-radical state laws, reports by Attorney General Palmer of gigantic communist plots — to a great many Americans it seemed that the United States was in danger of a Red take over. (Incidentally, while Americans were looking under their beds for communist spies, 15,000 United States soldiers were in Russia for the purpose, among other things, of aiding counter revolutionary forces.)

This hysteria was just that; it can only be understood within the context of the American penchant for believing in conspiracies. In the light of the facts, the panic was absurd. Absurd or not, it helped to contribute to some of the less attractive aspects of the 1920s: attempts to force the nation to conform to the traditional WASP model: anti-Catholicism, anti-Judaism, anti-foreignism, anti-evolutionism, antiliquor, anti-organized labor, anti-“radicalism”, pro-“100% Americanism,” textbook burnings, and loyalty oaths. These attitudes, in some ways, recall the North of the 1850s.

Then, of course, came the Great Depression. The activities of foreigners, communists or fascists, were well down on the list of worries, even when the fulminations of Gerald L.K. Smith and Father Coughlin are taken into account. With the disillusioning outcome of the war to end wars and make the world safe for democracy, it was no longer so easy to tell the good guys from the bad guys. When we entered World War II, the Soviet Union was our ally and so communism was no longer seen to be a threat. Did not our own Office of War Information describe Russia as one of the “freedom-loving democracies”? And when the Axis was crushed and the United Nations established, it looked as if the world had after all come to its senses, that it would be America writ large, a democratic federal republic, and thus would enter a permanent era of peace and prosperity—the millennium (though that word was not used).

But it did not happen. The Soviet Union did not remodel itself along American lines. It stood revealed as frighteningly, aggressively un-American, the source of a whole alien philosophy, anti-Christian and anti-capitalist, that was spreading like wildfire. The persistence and spread of Soviet-affiliated socialism set off familiar reactions: the belief that an alien conspiracy was responsible for everything bad that was happening. This great conspiracy, as always, was a deadly threat to everything we hold dear, and its goal was nothing less than the subjugation of the whole world and the imposition of its system everywhere. The source of this evil was the Soviet Union. Every manifestation of communism could be traced to that original source. Therefore communism was unified in its objectives; it was, as the phrase went, monolithic communism—all part of the same conspiracy, as the conspiracies of Satan always are. Since communism was determined to spread, we had to contain it. And because its philosophy and system were so obviously wrong and unworkable, if we contained it long enough, we could push it back, and eventually it would collapse. Lincoln had said much the same thing of the Slave Power Conspiracy in his famous House Divided speech. Nothing less would be acceptable, because the world would either become all slave or all free. There can be no compromise with evil, for then evil will triumph.

There is much in this that cannot be denied: the political and social system of the U.S.S.R. was utterly different from ours, as much so as Czarist Russia had been, perhaps. The utter ruthlessness of Stalinism is everywhere acknowledged-not least by the Russians. And there can be no doubt that the U.S.S.R. promoted the establishment of repressive socialist/communist regimes in other countries, and that it looked toward a world built on the Soviet model. Furthermore, the Soviets’ “theology,” like ours, told them that they must win in the end. They, too, had the millennialist dreams. However, to believe everything that happens contrary to our vision of what the world should be like is the result of any great conspiracy, capitalist or communist, is not to see the world as it is, and decisions based on such a shadow play are apt to produce, as they did in the 1850s. unexpected and unwanted results.

Like the antebellum conflict between North and South, the Cold War has gone through many phases that should have been hard to fit into a rigid formula. The communist monolith cracked here and there: Yugoslavia, Albania, and then the giant Red China fell away from the U.S.S.R. Although our announced policy fluctuated from the containment of Kennan to the liberation of Dulles to the legitimacy (with credibility) of Kissinger, for the most part we still held fast to our original assumptions and did not worry about these incongruities. It is true that things began to seem a little less simple than before; the old stereotypes and generalizations seemed a little out of touch with the facts. But it was Vietnam that shook us most deeply. Instead of being greeted as the redeemer of Vietnam, we were depicted as a great bully raining death on a small and impoverished nation in a war of saturation bombing, Agent Orange, and body counts. Instead of Bunker Hill, we had My Lai, and instead of a nation rallying to support the righteous cause of Americanism, we saw a divided nation demanding an end to a war that seemed to have no meaning. We went to Vietnam, we said, to give the Vietnamese a free choice, but while the enemy fought tenaciously for their beliefs, our allies seemed unwilling to die for their right to choose the American way. Faith in our ability to prevail was shaken: we put forth our strength in Vietnam and ended by escaping from the roof of the American embassy in Saigon. Then, to cap the climax, came the seizure of American hostages in Iran and our powerlessness to resolve the situation.

Consequently, many Americans came to be uncertain about our role in the world, humiliated by our failures abroad, disturbed by dissension at home, uneasy, directionless, suffering from “malaise.’’ Had we failed in our mission? Did we really have one? Was the American way after all the light of the world?

These Americans were ripe tor a leader who would reaffirm our role and purpose in the world, reaffirm our rightness and righteousness, reaffirm the continuing deadly danger of the evil, godless communist conspiracy, still spreading, still growing in strength, and who would make us once again the most powerful nation on earth. They were waiting for a leader who would do for them what Lincoln did for Republicans in 1858 in his House Divided speech. Was it not this that swept Ronald Reagan into office in 1980? Americans returned to a way of looking at the world and our own country that bears some remarkable resemblances to the Republican world-view of the 1850s.

Mr. Reagan was ideal for this role. His vision of the world had not been altered by the shifting tides of the Cold War or the failure in Vietnam. He was welcomed by a resurgent religiosity, much of it a fundamentalism so reminiscent of the 1850s. At the 1980 Republican convention, Jerry Falwell announced that Reagan and Bush were God’s instruments in rebuilding America, while the preceding speaker had described the Republicans as “the prayer party.” At a prayer breakfast Reagan announced that politics and religion were necessarily related, and that “without God, democracy will not and cannot long endure.’’ Reagan also said during his campaign that “this country…is hungry for a spiritual revival —one nation under God, indivisible.”

At the inauguration. Reagan’s personal minister stated that Reagan was chosen of God, and Reagan himself passed this along to the nation: it was chosen of God too. He proclaimed our moral superiority over any totalitarian society. The only morality the Russians recognized, Reagan announced in 1983, “is that which will further their cause, which is world revolution.” Those who lived in “totalitarian darkness,” he said, were the “focus of evil in the world,” comprising an “evil empire,” and the struggle against it was “the struggle between right and wrong, good and evil.” “There is sin and evil in the world and we are enjoined by Scripture and the Lord Jesus to oppose ti will all our might.”Reagan said there could be no compromise. He told of “hearing a young father, a very prominent young man in the entertainment world,” tell a California group that he “would rather see my little girls die now, still believing in God, than have them grow up under communism and one day die no longer believing in God.” Wherever in the world people have been enjoying democracy and religious worship, he declared, it has been due to “the protection of the United States military.”

This way of thinking was not confined to Reagan, but was echoed by other high officials and presumably shared by still more who have not yet been heard from. When the American Marines were attacked in Beirut, Admiral James D. Watkins, Chief of Naval Operations, blamed the deaths of 241 marines on “the forces of the anti-Christ.” “I have read the Book of Revelation,” said Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger to a Harvard student, “and, yes, I believe the world is going to end—by an act of God, I hope— but every day I think that time is running out…I worry that we will not have enough time to prevent nuclear war…I think time is running out…but I have faith.”

Reagan cited the Bible (Luke 14: 31-32) for the need for more defense spending, saying, “I don’t think the Lord that blessed this country as no other country has ever been blessed intends for us to someday negotiate because of our weakness.” Nor did Reagan shrink from contemplating the battle of Armageddon. Some have counted perhaps a dozen or more times when the President said that Armageddon might be near. He had looked at the old prophecies, he said, and studied “the signs foretelling Armageddon, and 1 find myself wondering if we are the generation that is going to see that come about.”

It was the old, familiar pattern: the irrepressible conflict, the war between good and evil; the great conspiracy overspreading the world: not seeing large facts that do not fit: simple explanations for complex events: an inability to distinguish between the important and unimportant: tainting all who disagree with at least unconscious disloyalty; taking to ourselves the responsibility for saving the world; defining salvation as a particular set of political, economic, and social institutions. The 1850s had come again.

Then in Reagan’s second term the world somehow seemed to change. Talk of Armageddon was heard no more. The advent of Gorbachev, glasnost, and perestroika, of Soviet initiatives in nuclear weapons reduction — things such as these had startling effects. The man who had hurled anathemas at the Evil Empire appeared in Moscow and was photographed speaking beneath a bust of Lenin. Asked by a reporter if he still believed the Soviets were the Evil Empire, Mr. Reagan just said. “No.” The man who had so powerfully revived the nation’s dormant faith in the unique mission of the Chosen People, the need to battle the great conspiracy, now warmly embraced the wielder of what just yesterday had been the deadliest weapon of the anti-Christ.

Had the Soviet Union seen the light? Was it undergoing conversion, regeneration, was it in the process of being born again in the image of our righteous republic, preparing at last to embrace the true faith of capitalism and Christianity? Or were these changes merely apparent, a shift in strategy by the infinitely cunning and treacherous minions of Hell, nothing more than another attempt to lull our suspicions and undermine our defenses? Had the President been deceived by the Russians, aided perhaps by the covert liberals in his own party, perhaps someone even closer to him? Aware of these fears, Mr. Reagan assured the faithful that he would take nothing on trust, that everything must be verified, he would deal from strength, and so forth. The chilling menace of Nicaragua’s Marxists-Leninists was reaffirmed, while Libya’s Muammar Qaddaffi was brought up in remembrance again as a sort of battered substitute Satan.

Surely these can scarcely be satisfying stand-ins for the Evil Empire for those who may be called the Apocalyptic Americans. The effect on them has been much the same as it would have been on Republicans in the 1850s if Abraham Lincoln, in his House Divided speech, had not attested his belief in the Slave Power Conspiracy, and had instead told his party that the South, while it would bear watching, was reforming itself along New England lines, but that although the Slave Power threat was receding, he would resolutely deal with the continuing danger to national security posed by the Sioux and the Apaches. One can imagine the psychic trauma produced by the resulting cognitive dissonance.

The convictions of Apocalyptic Americans, however, are of flinty durability. They know that this is not the first time false prophets have cast dust in the eyes of the nation, when events have seemed to discredit their eschatology. They know that Armageddon must come before Satan is bound. Even those who have never heard of Revelation or Armageddon know that, for in these people the apocalyptic vision seems to fill some deep emotional craving not necessarily derived from religious conviction. They will not allow their belief in gigantic evil conspiracies to be taken from them; after all. everyone needs something to believe in.

They will watch and wait.

Gorbachev may fail, there may be a reactionary coup in the Kremlin, arms reduction talks may collapse, a Marxist-Leninist revolution may overwhelm Mexico: many things may occur to show that the Evil Empire is alive and well. Then, as has happened before, they will be vindicated and will bring forth a new leader who will prepare the people to do battle for the Lord. And all nations will see the light and become just like us. The millennium will have arrived: the Chosen People’s final triumph in the great war that began so long ago in Charleston harbor. Then the South, now at last the world.

This article was originally published in the Second Quarter 1989 issue of Southern Partisan magazine.