In most minds today, the word segregation and the term “Jim Crow” immediately evoke a picture of the American South at the start of the Twentieth Century. It is, however, a false image that has been carefully crafted over the years to mask the actual genesis of the legal separation of black and white races in public facilities. This is particularly true in relation to Nineteenth Century public transportation.

While the first Southern segregation laws that were enacted in the latter part of the Nineteenth Century did apply to the seating in railroad passenger cars, such restrictions had been common practice in the North for many decades prior to that time. The situation in the South before the War Between the States was possibly best described by a New York City observer, Frederick Law Olmstead, who made an extensive tour of the South between 1852 and 1857. The “New York Daily Times” had employed Olmstead, a noted landscape architect who later created that city’s Central Park, to write a series of articles describing all aspects of life in the Southern states. The hundreds of accounts Olmstead wrote for the paper were used in his 1861 book “Journeys and Explorations in the Cotton Kingdom.”

Many of Olmstead’s personal observations of the antebellum South involved what he saw during his travels on railroads and stagecoaches. He once noted; “I am struck with the close co-habitation and association of black and white. Negro women are carrying black and white babies together in their arms; black and white children are playing together; black and white faces are constantly thrust together out of doors to see the train go by.”

In other accounts, he gave proof that the train lines in the South were not actually segregated at that time in history. While first class rail cars were reserved for white passengers in general, personal black servants, both male and female, who were traveling with their masters were allowed to be seated in such cars. In the case of regular second-class cars, there were no racial restrictions in the South and black and white passengers could and did sit together.

On one trip, Olmstead observed a white woman with her daughter together with two black women, one old and the other much younger. He noted; “They all talked and laughed together and the girls munched confectionery out of the same paper, with a familiarity and closeness of intimacy that would have been noticed with astonishment, if not with manifest displeasure, in almost any chance company at the North.”

In regard to his stagecoach travels, Olmstead once wrote; “Among our inside passengers was a free black woman; she was treated in no way differently from the white ladies.” He further noted that “. . . this was entirely customary at the South, and no Southerner would ever think of objecting to it.”

Conditions in the North during this period, however, were quite the opposite. America’s first rail line, the Baltimore and Ohio, began operations in 1830 on thirteen miles of track leading out of the nation’s second largest city at that time. Eight years later, the country’s fourth largest city, Boston, launched its own thirteen-mile train service, the Eastern Railroad Company, but unlike the the Baltimore and Ohio, this line began with completely segregated cars.

In August of 1838, the Massachusetts line started running its initial service from Boston to Salem. In a speech at the grand opening, the line’s president, George Peabody, predicted that rail travel would be “. . . a force for social change. Steam locomotion would bind together the sprawling United States and help subdue local prejudices. A rail-connected nation, east to west, north to south, would send a whole people moving onward together in a career of unexampled prosperity, bearing in their front the standard of equal rights.”

“Equal rights,” however, was not what the customers found the next day when the line opened for regular business. What they discovered were segregated cars for white and black passengers. The latter were dubbed “Jim Crow” cars by the local press, a name associated with a well-known minstrel performer of that day, Thomas Rice of New York, who used the term “Jim Crow” for his black-face stage character. Figurines of Rice’s comic caricature were even sold widely throughout the Northeast, as well as music boxes which played songs of his such as “Jump Jim Crow” and “Zip Coon.”

The practice of segregated railway cars quickly spread to many of the lines that later began operating in New England and ultimately to those throughout the North, as well as to other modes of public transportation. By 1841, the Massachusetts steamboats that ran from New Bedford to Nantucket Island were also segregated, with the same holding true for its associated train line, the New Bedford and Taunton Railroad.

During the follow decade, horse-drawn buses began to appear on the streets of New York City with a few of them bearing the sign “Colored persons allowed” and were, therefore, integrated if white people chose to ride in them . . . but few did. All of the other buses in the city, however, were for white passengers only.

In 1858, when horse-drawn streetcars were first put into service in Philadelphia, black passengers had to ride on the front platform and were not allowed to sit inside the cars. This practice was kept in force until 1867. Even as late as 1863, when horse-drawn streetcars first began to operate in San Francisco, they too were for white passengers only. Many black residents in the city filed suits against the streetcar company, but it was not until 1868 that black passengers were finally allowed to ride in the cars.

In the South, the first state to enact a railway segregation act after the Reconstruction period was Mississippi in 1888. The law called for rail lines to provide separate but equal cars for whites and blacks, as well as separate but equal rooms in their depots for white women and black passengers. Two years later, Louisiana passed a similar law, the Separate Car Act, with all other Southern states following suit during the next few years.

The 1890 Louisiana law was challenged two years later by a black man named Homer Plessy who refused to leave the white’s only car. Plessy was ejected from the train, jailed when he protested and later appeared in a state court before Judge Howard Ferguson. Plessy contended that separate cars violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments by not granting equal rights to black passengers. Judge Ferguson, however, ruled that the state law was constitutional and the matter was taken to the U. S. Supreme Court in 1896.

That year, the high court was composed of seven justices from the North and two from the South. The Northerners were Chief Justice Melville Fuller of Illinois and Associate Justices Henry Brown and Stephen Field of California, Horace Gray of Massachusetts, George Shiras of Pennsylvania, Rufus Peckham of New York and David Brewer of Kansas. The two Southerners were Edward White of Louisiana and John Harlan of Kentucky.

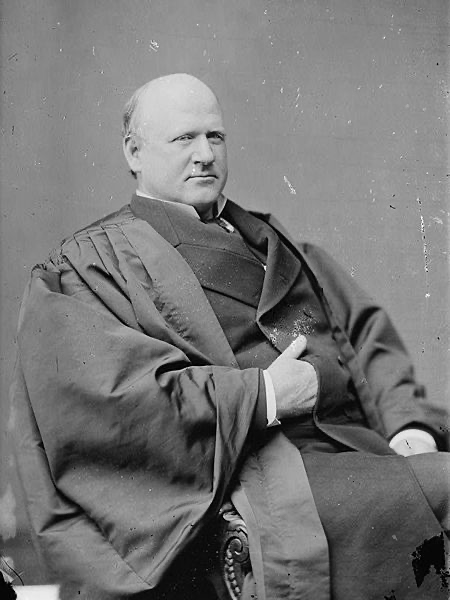

Due to the death of his daughter, Justice Brewer was not in attendance when the case was adjudicated that April. By a seven to one majority, the court ruled in favor of Judge Ferguson, thereby allowing the Louisiana railway segregation law to stand. Of the two jurists from the South, while Justice White voted to uphold his state’s law, Justice Harlan’s vote was the only one against it. He also wrote a searing dissenting opinion.

Harlan was no stranger to dissent though and became known as the high court’s “Great Dissenter.” During his thirty-four years on the Supreme Court he voted “no” in almost nine hundred cases and wrote a hundred twenty-three dissenting opinions, many of which involved civil rights. Even though he had once been a slave holder in Kentucky and had opposed Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, as well as the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, on the grounds that they were all unconstitutional, Harlan had also opposed his state’s secession effort and had commanded a Union regiment during the first two years of the War. During the Reconstruction period, Harlan became a Republican, a strong advocate of civil rights and a defender of minorities. Many of his written dissents also helped influence a number of important high court rulings on civil rights a half century later.

In his 1896 opinion, Harlan wrote in part; “In the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is colorblind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful . . . The arbitrary separation of citizens on the basis of race, while they are on a public highway, is a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution. It cannot be justified upon any legal grounds. The present decision, it may well be appreciated, will not only stimulate aggressions, more or less brutal and irritating, upon the admitted rights of colored citizens, but will encourage the belief that it is possible, by means of state enactments, to defeat the beneficial purposes which the people of the United States had in view when they adopted the recent amendments of the Constitution.”

Justice Harlan’s prescient views proved to be most prophetic, as the matter of Plessy v. Ferguson became a landmark case which set a precedent that upheld numerous future Supreme Court decisions involving a state’s separate but equal segregation laws dealing with public education, transportation and accommodations. Because of Plessy v. Ferguson, all such laws remained in place until 1954, when the Supreme Court decided in the case of Brown v. Board of Education that such laws were unconstitutional. Even so, many areas still defied the court’s ruling and it took another decade before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 finally struck down all forms of de jure segregation in America.

I appreciate this truth. I still remember when I was about 7 years old, maybe 67 or 68 when an old man prevented me from drinking from the public water fountain. At that time a big teen age black man came and drank from the fountain. Saying the water was good. I just walked away not understanding what was happening. Not till many riots and years later did I begin to understand that so called, “Jim Crow!” did not come from the South.

This happened in, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Jimmy D. Jacobson