By October 1864, the city of Charleston, South Carolina had been undergoing a bombardment for over a year. The Federal forces were in full possession of nearby Morris Island, and had all but neutralized Fort Sumter’s offensive capabilities. During the previous summer, Union batteries near Morris Island began sending their deadly fire into Charleston, the first attack on the city beginning in the latter part of August 1863. On August 21, 1863, the Union commander General Quincy A. Gillmore sent a letter to General P.G.T. Beauregard, the Confederate commander, demanding the “immediate evacuation of Morris Island and Fort Sumter.” If this demand was refused, Gillmore stated that he would “open fire on city of Charleston from batteries already established within easy and effective range of the heart of the city.”

Fitzgerald Ross, a foreign newspaper correspondent in Charleston at the time, wrote about the ultimatum sent to General Beauregard and the initial shelling of the city that began in the middle of the night (misspelling Gillmore’s name):

Next morning we heard of the “fair warning” General Gilmore had given of his intention to shell the city. It seems that at nine o’clock in the evening a note had been sent to the commanding officer at Fort Wagner to forward to General Beauregard, in which it was demanded that Fort Wagner, Fort Sumter, and the other defences of the harbour, should be immediately given up to the Yankees; if not, the city would be shelled. Four hours were graciously given to General Beauregard to make up his mind, and to remove women and children to a place of safety. The note was entirely anonymous, no one having taken the trouble to sign it. It reached General Beauregard about midnight, and was of course returned for signature and without an answer. At half past-one the shelling commenced. No doubt General Gilmore wished that the effects of the bombardment should have their influence on General Beauregard before it was possible that he should give an answer to the summons…It is rather an extraordinary proceeding, to say the least of it, to bombard the city because the harbour defences, which are three and four miles distant, cannot be taken; and the attempt to destroy it by Greek fire is very abominable; but the spite of the Yankees against Charleston, “the hotbed of the rebellion,” is so intense that they would do anything to gratify it.

Frank Vizetelly, a correspondent for the Illustrated London News, was staying at the Charleston Hotel when the first shells began falling into the city in the middle of the night. The guests began flying out of the hotel in a panic, and he made a sketch of what he witnessed in the street. He also commented on his drawing, stating that General Gillmore,

…thwarted in his attempts on Battery Wagner and smarting at his frequent repulses, has demanded the surrender of the last-named work or has threatened to shell the city; and, in violation of all rules of warfare, he has turned his guns on unoffending women and children.

On August 22, 1863, General Beauregard penned an angry reply to Gillmore’s demand for surrender, accusing him of barbarity.

Among nations not barbarous the usages of war prescribe that when a city is about to be attacked timely notice shall be given by the attacking commander, in order that non-combatants may have an opportunity for withdrawing beyond its limits. Generally the time allowed is from one to three days—that is, time for a withdrawal in good faith of at least the women and children. You, Sir, give only four hours, knowing that your notice, under existing circumstances, could not reach me in less than two hours, and that not less than the same time would be required for an answer to be conveyed from this city to Battery Wagner.

With this knowledge you threaten to open fire on the city, not to oblige its surrender, but to force me to evacuate these works, which you, assisted by a great naval force, have been attacking in vain for more than forty days.

Batteries Wagner and Gregg are nearly due north from your batteries on Morris Island, and in distance therefrom varying from half a mile to two and a quarter miles. This city, on the other hand, is to the northwest, and quite five miles distant from the battery opened against it this morning. It would appear, Sir, that, despairing of reducing these works, you now resort to the novel measure of turning your guns against the old men, the women and children, and the hospitals of a sleeping city—an act of inexcusable barbarity…

Your omission to attach your signature to such a grave paper must show the recklessness of the course upon which you have adventured, while the facts that you knowingly fixed a limit for receiving an answer to your demand which it made almost beyond the possibility of receiving any reply within that time, and that you actually did open fire and throw a number of the most destructive missiles ever used in war into the midst of a city taken unawares, and filled with sleeping women and children, will give you a bad eminence in history—even in the history of this war.

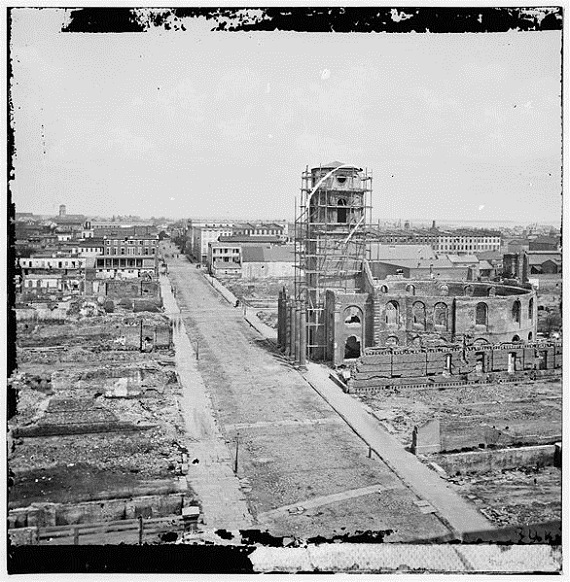

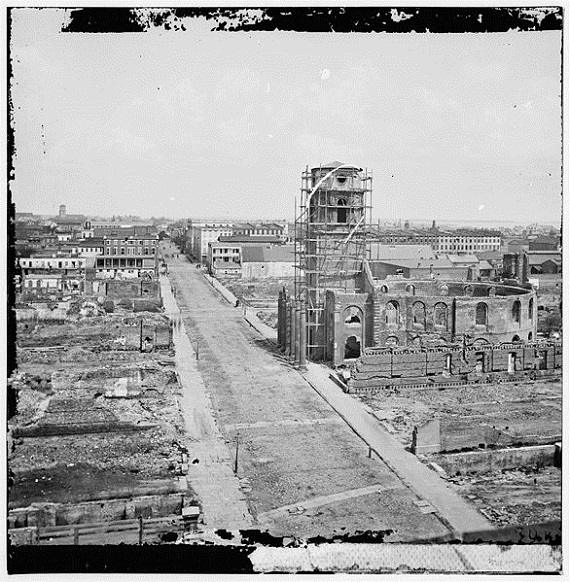

Gillmore’s reply, also dated August 22, claimed that he “had been led to believe…that most of the women and children of Charleston were long since removed from the city.” He agreed to suspend the bombardment until 11 P.M. the next day so that civilians could evacuate the city. From August 22 onward until mid-November 1863, only a few more shots were fired into Charleston. After that, the bombardment continued in varying degrees of intensity until February 1865. It lasted some 545 days, becoming the longest siege in the history of modern warfare up to that time.

Captain Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, a Confederate ordnance officer in Charleston, expressed the opinion that Gillmore’s attack on Charleston was “without military significance,” and recalled that an old black woman who sold nuts in the market was later blown to bits by a Federal shell. The bombardment, he said, was “absolutely without effect on the progress of the siege, and was clearly & purely spite!”

Beauregard’s successor, General Samuel Jones, quickly grew frustrated with the relentless bombardment of non-military targets in Charleston. He corresponded with the new Union commander, General John G. Foster, who asserted that the whole city of Charleston was a target, since it contained an arsenal and military foundries, but in June 1864, Jones replied to Foster complaining that the bombardment was not accomplishing any military purpose. Jones argued:

The manner in which the fire has been directed from the commencement shows beyond doubt that its object was the destruction of the city itself…and not…to destroy certain military and naval works in and immediately around it; for if [these] works…had been the marks, the fire has been so singularly wild and inaccurate that no one who has ever witnessed it would suspect its object…The shells have been thrown at random, at any and all hours, day and night, falling promiscuously in the heart of the city, at points remote from each other and from the [military and naval] works…They have not fallen in or been concentrated for any time upon any particular locality, as would have been the case if directed on a particular fixed object for night firing; but they have searched the city in every direction, indicating no purpose or expectation on the part of those directing the fire of accomplishing any military result, but rather the design of destroying private property and killing some persons…most probably women and children quietly sleeping in their accustomed beds…We direct our fire only on your batteries, shipping and troops.

In her book Charleston, The Place and the People, published in 1912, Charlestonian Harriott Horry Ravenel wrote about the effects of the initial bombardment in the city:

[O]n the twenty-second of August, at half after one A.M., a screaming shell flew over the sleeping town, and burst in a yard beyond the Battery. In a moment the town awoke ; another and another ! The alarm and horror were indescribable, for at first people thought the city was taken…On East Battery a boy, brought home from camp, was lying desperately ill. The shells fell about the house. An ambulance was sent for, the lad’s sister got in and took his head on her lap. A gentleman rode ahead to seek a refuge. They drove at a foot’s pace — their way lighted by the bursting bombs, until out of range. There a kind friend took them in; the boy died next day. There were cases of women in dire distress…

It need hardly be said that this proceeding did not advance by one hour the progress of the siege or the fall of the city. There was at the moment much individual suffering. A few unhappy women and new-born infants died of it. This was the sole advantage gained by the Federal commander.