Many years ago I spent five fantastic weeks in Boston during the fall. Though I had heard about the explosive colors of autumn in New England, it truly was a sight to see. So too were the two games I attended at Fenway Park, only a year after the Red Sox swept the Rockies in the World Series. But the fondest memory I have from my time there was the treatment I received from several Southern transplant families who were in a Bible study at a local Presbyterian church (at the time I was both Presbyterian and a part-time student at Reformed Theological Seminary).

One family, originally from North Carolina, allowed me to park my car outside their suburban home so I didn’t have to pay the additional garage fees at my hotel in the city (they also hosted me for a meal every weekend). Another from Georgia met me a few times for dinner, while yet another from Kentucky had me over for beers a couple of evenings. All of it meant the world to a young single guy in a new city who would have otherwise spent most of that time reading alone at a bar near his hotel, just to keep away the loneliness blues.

Several years later, after marrying my wife, we too tried to exhibit that same Southern hospitality I had so gratefully enjoyed not only in Boston, but in many homes in my native Virginia. Little did we realize we’d have occasion to do the same on the other side of the world when we moved to Thailand in 2014. Nevertheless, it was in Southeast Asia, of all places, that I truly learned how to practice that form of Christian charity to neighbors (and strangers) so prolific across Dixie.

The opportunity for this lesson in hospitality was an unexpected one. Shortly after arriving in Bangkok, I introduced myself to some Pakistanis at our local Catholic parish. I had previously served in Afghanistan, had learned the language (Dari), and had developed a deep interest in South Asian culture. The story of the Pakistani Catholics I met was quite a harrowing one.

It had begun more than five years earlier, in the megalopolis of Karachi, which is inundated not only with criminal gangs, but ethnic Pashtuns who often identify with the extremist form of Islam practiced by the Taliban, which is also predominantly Pashtun. These militant Muslims harassed Pakistani Christians, accused them of blasphemy, threatened their lives, and sometimes even tried to kill them. The first Pakistani Catholic family I met in Bangkok included two young women who had been set aflame by Muslim extremists, and a husband and wife who had been shot at by another.

Thus these Pakistanis, by the thousands, fled their native land, where many of them had practiced their faith for generations, often dating back at least to the British colonial period, when many had converted to Christianity. Many chose Thailand because the country, a major tourist destination, provides 30-day visas to new arrivals. Then the Pakistani migrants would apply to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, or UNHCR, for refugee status, in the hopes of being resettled somewhere in Europe or North America. In the vast majority of cases, those applications were denied, leaving the migrants at the mercy of corrupt Thai police and immigration officials, who used their authorities to harass and extort the asylum seekers.

In short, the whole thing was a humanitarian crisis, and practically no one anywhere in the world even knew it was happening. Obviously anyone with a charitable bone in his body would express sympathy for these people. But my wife Claire and I felt that much more could be done.

So we did what the Southerners in Boston had done for me many years before. We tried to help them with their problems, including reviewing and editing their petitions to the UNHCR when their initial applications were rejected. We gave them money to pay for their basic needs, including food, clothing, medical expenses, and schooling. And we invited them into our home.

One memorable such visit happened following the arrival of their former parish priest in Karachi, Fr. Thomas, an older and very serious gentleman in somewhat poor health with limited mobility. So I put the priest and one of the Pakistanis, a good friend Wilson, on Thai motorbike taxis and sent them off to our apartment to be greeted by my wife, a Southern belle from Georgia. Though our abode was not particularly lavish in comparison to many Western expats in Thailand, it still made Claire and I uneasy to host these hardened persecuted Christians who had suffered threats and violence, and now slept on cement subflooring packed into a couple tight rooms without air conditioning. For them, our three-bedroom apartment must have seemed palatial.

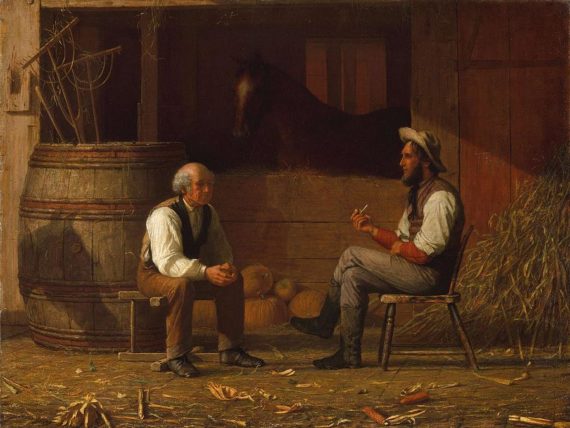

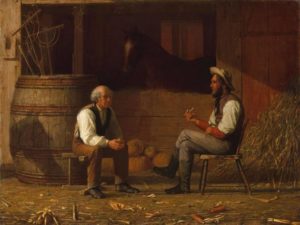

If our Pakistani friends felt frustrated or jealous that they, who remained faithful to Christ in the face of terrible suffering across thousands of miles, endured countless hardships while my family lived in comfortable security, they never showed it. I suppose this reflects the mark of true hospitality and Christian fellowship: you present yourself well, offer your very best to your neighbor, and allow charity and empathy to cover over the many forms of insecurity and tension that comes from varying degrees of wealth or class. Perhaps the church potluck or picnic serves as an exemplar of this behavior, where wealthy elites dine on the same fare, and sit at the same tables, as blue-collar, working-class folk. All are welcome, and in a sense equal, at the feast.

Trying to exhibit that Southern Christian hospitality became even more real when another Pakistani family we befriended, the D’Souzas, was imprisoned in the nefarious Immigration Detention Center, or IDC, for overstaying their visas. It was a horrible, overcrowded place, run by corrupt Thai officials who mistreated and abused detainees. Illness was rampant.

Claire began weekly visits to the D’Souzas at the IDC, bringing them all manner of food, toiletries, and other little things to make their detention a little more bearable. I would visit less frequently when I could get off from work. When we came, we would be separated from the D’Souzas, a family of five that included a little baby girl born in Thailand, by a tall metal fence. Crammed up against the fence with scores of other visitors and detainees, we would have to shout to be heard, and learn from the D’Souza’s what they needed next time we visited.

This went on for many months, almost a year, until the D’Souza’s health so deteriorated that in summer 2017 they told us they would rather return to Pakistan, where the father Michael D’Souza has several times been physically assaulted by Muslim extremists, than stay in the IDC. Once more Claire and I sprang into action, soliciting the required money from friends and family to pay for the D’Souza’s airfare. They departed Bangkok a few days before we too moved away, back to the United States and my beloved Virginia.

The next March, Michael, who had purchased a motorized rickshaw, was identified by the same Muslim extremists who had targeted him many years before. They dragged him out of the rickshaw, beat him almost to death, and torched his only source of income. He and his family live in hiding in a suburb of Karachi to this day, largely reliant on money provided by my wife’s parents in Atlanta. They remain prayerful that someday God will bring an end to this trial.

This is obviously a sad story, though also a universal, and perhaps even hopeful one. Hospitality, of course, is not unique to Southern culture. Indeed, the Pakistani Christians we befriended exhibited their own gracious style, often cooking food for me to take home to my family… although it was so spicy, only I was able to handle it! But the reasons for Southern and Pakistani Christian hospitality overlap in important respects: a deeply religious culture; an emphasis on family and tradition; and a desire to bless the neighbor and the stranger in order to exemplify the love we have known from a gracious, eternal God who never abandons us.

I am grateful that while in Thailand I was able to extend a little bit of that Christian charity on behalf of my native Dixie, and to receive a good bit in return from a very surprising source. How could I, or any conscientious Southerner, do any other? Contrary to so many absurd caricatures, we are a people who, as our God calls us, care for the foreigner and sojourner in the land (Deut. 10:19). Indeed, we have elected multiple governors of South Asian lineage (both second generation Americans)! To be a Southerner is to have a gracious heart, and welcome those in need into our homes and communities, whether we are at home in Alabama, or transplanted to Boston or Thailand. It is a heritage worthy of our pride and our preservation.